I had the good fortune to speak to Ry Cooder for the issue of Uncut that’s just come off sale (quick plug: you can read all about the new issue here).

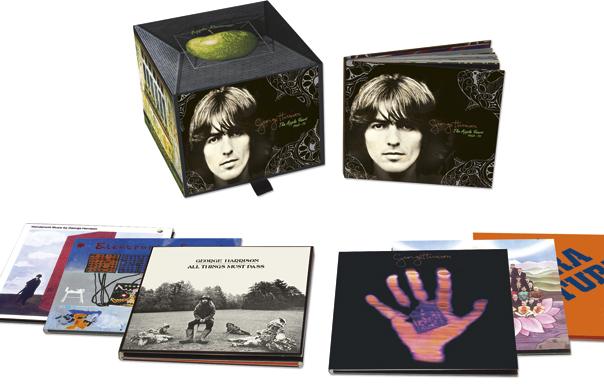

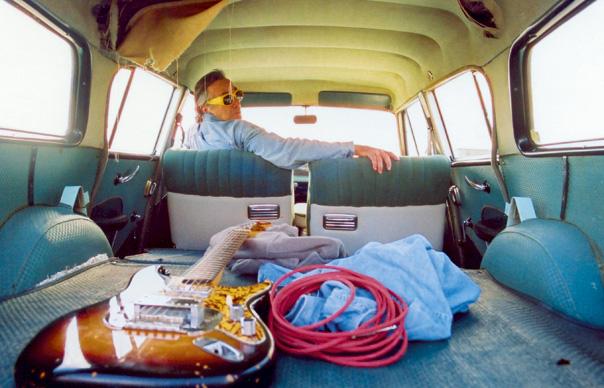

The interview was tied into a new box set which compiles seven of his legendary film soundtrack called – surprisingly enough – Soundtracks. I can’t stress how brilliant this music is – whether it be the dusty twang of Paris, Texas, the American folk idioms of The Long Riders or the experimental jazz of Trespass. On reflection, I suppose my introduction to Cooder’s music came through his soundtrack work: certainly, the vinyl Paris, Texas album was the first record of his that I bought, and I soaked up those Walter Hill movies he scored long before I explored the hefty body of work he recorded in the Seventies.

Anyway, there was only room for a few hundred words of Q&A to accompany my review of the box set (I’ll post that separately in the next week or so). But here’s the full interview transcript – it runs close to 5,00 words, and covers Performance, his marvellous collaborations with Hill, scoring Paris, Texas and – joy of joys – Cooder even reveals he might soon make a return to soundtrack work…

__________

How did you first become involved with soundtrack work?

Let’s see. It must have been in the Sixties, of course, when I had occasions to work with Jack Nitzsche. I sort of got started that way. He had, there was a time when he sort of, I don’t know how it happened but he ventured into doing that kind of work, soundtrack work, particularly with Candy, that was Terry Southern’s story about the girl. Then that fizzled out, that didn’t work, the studio didn’t like what he wanted to do. He wanted to bring pop music into the scores. Because nobody was doing that then, not really. There was a sort of Hollywood version of pop music in movie scores, kind of hokey and stupid, but what he wanted to do was bring interesting people that he knew in pop, in that world, into the texture, into the grain, the palette of it, you know. Then he got the job to do Performance and so that’s what did it. So that was the perfect opportunity to establish this as an idea, see. And I was part of that score and others were there, of course, Randy Newman, Buffy Sainte-Marie and so forth. It’s quite a good team, very interesting. Then Milt Holland, who was the great world percussionist I met then, he came with him koblas and his strange drums and his weird inventions that he and friends had, these old time percussion beatniks had. You could see that this was fun, you know, this is interesting. You look at the film and play at it. We weren’t dealing with written arrangements or orchestrations in that context, whatever the direction was we went with it. I found it could be something I could comprehend, because I didn’t have formal training and certainly didn’t have the slightest idea of composition or shall we say formal harmony. But that was at a time of change. The films were changing, too. So people who were making films, the directors and producers and so forth, these are also people who like pop music, naturally, everybody did and it was coming up fast. There was a whole lifestyle indicator there, right? People in film wanted to be hip. They were younger and they wanted to have long hair and hang around with rock musicians and the whole thing was taking shape. So working with Jack was like taking a class. Okay, I don’t know what this is, let’s try it. Okay I can do that, I understand to the extent that I’m able. And then a little later on when Walter Hill called to ask me if I’d score Long Riders, it was pretty much the same idea that I had. I said, sure we’ve got people in Western clothes and horses, robbing banks and trains. He liked one of my records that he wanted me to replicate.

“A little later on”? It’s a ten year jump between Performance and The Long Riders.

He called, I had done this record called Jazz which I didn’t particularly like but he liked it and he saw that it could apply. That kind of ensemble, those kind of instruments could work in a nice way with the time and the place and move the film along. In those days, Walter he had a presence, he had chops, and people would do as he asked. There wasn’t any opposition, it wasn’t like the studios were saying ‘No, you can’t do that’, or arguing with him. You didn’t argue with Walter in those days. He was the man, he set it up and that was it. So I went in there and said ‘Sure, we’ll do that.’ I didn’t think twice about it. I got a little band together, it was a very good little band.

Who was in the band?

Oh, well, David Lindley was in the band. You had country guys, Tom Sauber was there, Curt Bouderse, some of these old time musicians out here on the west coast who played that old time stuff, you know, fiddle, banjos and traditional instruments, came, were very good. Keltner, yeah. It was great, it was fun. I map these things out according to what I thought a scene should sound like. We just sort of breezed through it. It was a nice job and it went well and me and Walter got on real well. So I kept working for him. He liked this kind of indigenous approach, such as you might call it, whatever music the time and place sounds like. He didn’t care much for the overlaid score which is compositional and geometric, if you see what I mean. I couldn’t do that anyway. We all understood that. If that was the need, I wouldn’t have been there. So those films that I worked for him on, they all seemed to accept it was a good fit, as they say.

What do you think connects you and Walter Hill?

Because he likes stories and he’s a history fan – US history I should say – and very much trying to go back to the John Ford films, looking at the guns, looking at the saddles and the hats and the clothes at a time when you would make films about people who talk this way and act this way, little communities, little groups of people, rather than the modern tendency which is huge groups of people and everything big and everything fast. So the tempo of those times suited him. Of course, he also had his other films that he did that I didn’t work on. As his films got more complicated – depending on the story, you know – some of those later ones he did I had some trouble with. But generally speaking, I like working for him because I like the stories. That’s what interests me, too. You can say I know what this character sounds like, or I know what this is supposed to do musically. We used to do funny things. We used to have budgets. So in that regard, we used to be able to take time – which they would never do any more, nobody would do this now – some of these instruments were invented, procedures are invented on the spot, and just experimented with. The more you did that, the better he liked it because he said, ‘Well, you know, you’re going towards something that’s unique and it’s going to be great, it’s not something anybody else has got.’ That was fun, too. It was excited.

Why do you think Paris, Texas was so successful?

It was a sound and an image that went perfectly together. The fact that Wenders had been such an arty kind of guy, European in feeling, so he has this whose first third of the film’s Harry Dean character just wandering around out there in the desert because he loved the desert. He was a good shooter, Wim, he photographed well, so it looked great. So what are you going to do out there? Try for some naturalness, some nature tone, some sort of blending of wind sounds and air sounds? It’s not going to have any fancy harmonic references or other kinds of consciousness inserted into it. It’s too little a boat. That was the thing Wenders was frightened about because he had three days to do this. He was on deadline, he had to go to Cannes festival and he had to get done. So I said, ‘Jeez, what do you want to do?’ He said, ‘Play Blind Willie Johnson, it’ll probably be okay.’ There’s nothing to it. It’s a mood, that kind of lonely sound. Trouble with guitars, though, you always picture one guy in a chair playing the guitar, you don’t want that, it’s not good, you want to evoke something spatially rather start thinking about people who are playing the instruments, that’s a no-no. but in this case, we were able to move the tone centres around pretty good, and it’s just a tone centred idea with this little guitar thing noodling along. It’s perfect for the film, it’s just great. It’s one of these rare things. We didn’t have time to think about it, didn’t have time to worry about it, just had no time but three days, get in there and get thing done so he can tear ass over to the Cannes Film Festival. But it worked pretty good. Of course, people loved the film. The film was unusual and it was on time, I think it was the times. Walter used to say to me, he used to say a lot of things, one of the things he said was ‘Timing is everything, if you’re too early it’s no good, if you’re too late it’s no good.’ You’ve got to be there with what people will respond to. That’s changing and shifting all the time, more so now than ever before. Not in a good way, either. But in those days of Paris, Texas, when that film came out it struck people as worthwhile and even important that they could identify with this character lost in this wilderness. They got something out of it. It’s a very well written film, see.

The vocal track with Harry Dean’s “I knew these people…” speech is such a stand out…

I always like spoken word records. I always really enjoyed those. They’d gone out of popularity, by the time this film came along, nobody bothered with spoken word, whether it was Ferlinghetti poems or some sort of radio drama then put on a disc. It was an LP era thing, and we were passing out of the LP era. People didn’t have the presence of mind or the time to sit around listen to somebody recite poetry on record, it was unheard of at that point. So of course the record company didn’t particularly care for it, but they didn’t particularly have anything to say about it. It’s a film score so they weren’t looking at it fortunately in the same way they would look at pop records that they were making which had to have an exact configuration – you have to have hits, number one, hit two, hit three, hit four. Four minutes max and so on, has to sound like FM radio and all that. So naturally the score didn’t have to adhere to these things, so what it’s based on is, is the film popular? If the film is popular at all, then the record might sell. They’re looking at a marginal thing, but it’s good to have. Nowadays, nobody does this, I mean, for God’s sakes, a score record like this where we would actually create things, do things for the record that weren’t in the film, such as Jim Keach singing ‘This here was our situation’ [‘Wildwood Boys’, from The Long Riders], that thing is a nice song but it doesn’t exist in the film. It sells the story of the film, makes an interesting record. We had really good opportunities back then to do this kind of work. You can’t do it anymore.

What does Jim Keltner bring to a session that’s so unique?

Jim and I worked together quite a lot at the time. I had my own records I made on which he played. Then these scores, it was natural to have him there. He had a spatiality in his playing, like jazz musicians do, as opposed to straight rock musicians who don’t have any. There’s no space in rock, it’s so compressed, it’s so hard and it’s so unyielding and what it’s doing is selling something. And that’s not what I was ever trying to do. I was trying to create some sort of environment. Part of that has to do with swing. We talk about swing practically in a historical context only. Where is that now? Who’s doing that? What environment do you find that in? You don’t. I used to think it was human nature, now I think it’s generational for Christ’s sake. In the film, Jim was especially good, of course. Being basically a jazz musician at heart, I think he could play to the film. Drum people, they wouldn’t. Drummers hit their drum and that’s it. But he could look at the film and be affected by it, be motivated by it. That’s what I used to say to anybody I was playing with, ‘Watch this scene and look what happens here, here and here. Here’s something you need to look at, then a little ways more here this guy does this, and then this happens. Don’t look at the floor, or something, look at the film.’ You used to have to make people do it. ‘Will you please, you’re not looking, see you’re not watching because you missed this moment here, we’re scoring a goddam film but we’re not doing it with written, where it’s timed out on a clock.’ That’s another technique, you know. Sometimes I’d do that. There were times when that had to be done that way. But to interpret, music as interpretive, some of these folk type things, vernacular music, its interpretive if you let it be that way. Don’t think in terms of the song, don’t think in terms of a hit record or what you’re used to doing. And Jim, of course, had good reflexes and a good eye for the moving image. It’s important. Otherwise you have a room full of rock guys who don’t give a damn what’s going on on the screen, and that’s no good. Then you’re not doing your work right, you’re not doing your job.

You’re incredibly busy during 1980 – 1986…

They keep coming. It was a lot of work, and it was hard work. One thing I did learn from doing the films was these people were big time workaholic type cats I hadn’t met before. As far as they were concerned, a scoring session started at nine and was done by six. But during that time, you worked non stop, you didn’t eat lunch. It was ridiculous. I’m sure actors have to have lunch, it’s in their contact, but we didn’t. We sat there at eight thirty, got going. You had to know what you were going to do. You had a nine o’clock downbeat and you’d get going. And you’d sit there all day until six o’clock, which nobody in pop music ever even heard of. It was like a regular gig. That’s the film business. It really showed me how efficient it could be, you can get a lot done. Also, you have to tweak yourself up, get moving faster, instead of sitting around twiddling your thumbs and thinking about, ‘Should I should have the vegan burger or the turkey burger? I’m not sure. Better sit and think about it a while.’ Nothing like that. You get moving, if Walter was there before you were. If you didn’t have something to do at 9 o’clock, it had better be good. And if it wasn’t good, you’d do it again. And if that wasn’t good, you’d do it again. You don’t stop. Nobody stops. At the end of the day, you drag yourself out of there, but I was younger then. I liked it. And then I got to be used to the idea of just a different pace and getting more done and it helped me knowing that, you could do that, it was helpful, I think, later on it was worthwhile because they don’t waste time so you shouldn’t waste time. If you get going and the going is good, then you want to keep going. I had one engineer one time, burst into tears. He said, ‘I can’t sit here. I need to get a smoke, I need to get a cup of coffee.’ I said, ‘You sit right there. If I’m going to sit here, you’re going to sit here.’ The guy started sobbing on the talkback. ‘You get somebody who can, then. Right now. I’m not going to get up off this chair and you’re not.’ He got a substitute right then. I said, ‘Alright then, whoever you are, you strap on, we’re going. We’ve got a job to do.’ You didn’t want these studio types showing up. ‘What’s happening? How many men on the dig? I don’t see the pages.’ One guy came one time from the studio. ‘I don’t see the pages.’ Walter said, ‘You leave him alone. Don’t you come in here.’ Oh, he was great, the toughest guy, man, he was tough. He protected me from those people. In those days, he could do that.

How long on average would a soundtrack typically take?

Oh, well, Southern Comfort was a breeze because it was only like 15 minutes long. We did that in a week. On the other hand, Crossroads, we worked on that for a year. Sure, because there was preparation, there was a certain amount of pre-record to do. Since it was about music, there was a lot of music. Once the film was shot and edited they had to go back over it and dub in all the guitar parts that had to be dubbed in, stuff had to be redone. A lot of work. That’s a musical film, though. Those things require.. I mean, how long did they work on The wizard Of Oz, for God’s sake? Depends on the story. Geronimo was a huge amount of work. That involved 80 piece orchestras and Indians and Tuvans and all kinds of crazy people on that thing, that’s a real circus that score. I mean, I got these Tuvans and brought them down from Canada. They were on tour. Nobody had ever seen anything like it. Throat singers? What the hell? Because Walter said, ‘The Indians have to have their sound. It better be good.’ So I said, ‘Okay.’ I stumbled onto this throat singing thing and found that these four guys were in Canada. I went up and flew them down. I drove around with them for two weeks in Canada, flew them down here. It was amazing. But in those days, we would do that kind of thing. Walter Hill, man. Whatever it took. It was great. Now, that’s impossible. It literally cannot be done. Anything close to that can never be done again. There’s no money, nobody cares, the studios run these things now, they hate music. They don’t give you a goddam enough money to get a pastrami sandwich now. You’re on your own. I think.

Trespass is the least conventional album in this set. What do you remember about recording it?

I figured Jon Hassell’s time to get Jon Hassell in there and play some weird grooves and get some tone centres. It was a very hard film to score. It’s so claustrophobic and so overwrought. And then you had to deal with the hip hop side of it. They had to reflect the two Ice guys with it, it had to have tension music mostly, danger music, and then some kind of desolation. That’s the Jon Hassell speciality. Jon Hassell’s Mr Desolation. There’s nobody as desolate and solitary as the sound of what he does on trumpet, there’s just nobody like that. So that was very interesting to get him in there, totally visual, totally spatial, Hassell’s unique in my experience. All through time, nobody can do what he can do. So that was lucky to get him in there. Walter was crazy, as soon as he heard that one note come snaking out, he was like “Oh, my God, who is this guy?” Well this is the man here. There’s no other instrument that can make that happen. Then other things were good. Rhythm things were really good in there. And so it worked. It was a stretch. A very experimental, very abstract, but I think it worked very well.

After Get Rhythm, soundtracks are your principle creative outlet until Chavez Ravine in 2005. Is there a reason for that?

Yeah, kind of is. I’ve never been able to plan anything. Or predict anything. So you don’t know what you’re going to do. I don’t know. Some people have career plans, long range career plans, I don’t know anything about that. I’m no good at it. It doesn’t mean anything to me. But one thing, one thing was, one issue was making solo records as far as I was concerned at a certain point, it just fizzled out. I couldn’t see it, I couldn’t make headway. Nobody bought ‘em, I didn’t like ‘em particularly, it was too hard to keep coming up with this stuff that nobody seemed to care about, and then the need to go out on tour and back these things up on tour it got to be impossible for me, I just couldn’t stand it. It was uneconomic, I couldn’t afford it, I’d find myself out in strange towns – “What am I doing here?” – this weird feeling of being in the wrong place, it’s a bad feeling so if you’re going to play music for an audience and you don’t want to be there you shouldn’t do it. So I said alright, I quit. Luckily, Walter was there and the films. There was others, too, not just him, but I mean it was a living, a good living and an interesting way to work and it went on for a while. Then other things presented themselves, such as Buena Vista Social Club, that came out of the blue, it was a fluke, that started a whole new phase with a bang, and it was good because by that time the film work had dried up for me. You go through these phases. That’s how life is. Over the long term, you just can’t do one thing. I saw that back in the Sixties when I was getting started. You better have some stuff in your bag that you can pull out if you need to. One time you do this, another time you do something else. What I told my son Joaquim, ‘Always try to do as many different things as you possibly can, especially when you’re starting out. Then people see what you can do, plus then you see what you might like to do or what’s available to do.’ I remember one time Mac Rebbenack said he used to take every session call on every instrument regardless of whether he could play it or not. I said, ‘You don’t mean somebody would call you on saxophone?’ He said, ‘Oh, yeah. Often.’ I said, ‘You go on there and play saxophone? You’re not a saxophone player.’ He said, ‘Well, I can do something. I played a couple of notes. It was okay.’ I said, ‘I’ll be goddamned, that’s alright. That’s brave.’ Make it work, you see. It’s not how many notes, it’s now good.

Would you ever consider recording another soundtrack?

Well, as a matter of fact, oddly enough, coincidentally, my son Joaquim is very good at this. He grew up drawing crayons on the floor while we scored Long Riders, so he grew up watching and listening, he absorbed this, he’s very good at it. He’s done some films himself, small film, very well. He doesn’t play melody instruments like I do. He samples. He’s got a whole treasure trove of stuff of mine that he finds in boxes that he can now with technology repurpose, as they say, and make these amazing composits and do all this work. It’s very modern and very good. And I have been some times, if he says come over and play on this or that thing, and I do. So he’s after me to do this work again, he said, ‘You’re missing the boat,’ he said. ‘People are copying you right and left,’ he said, ‘All these TV shows you never watch,’ he said, ‘You should see what they’re doing…’ So he’s all up for me to do this, so yesterday, it’s funny, we took a ride, he and I, and we went to see a film agent. He had found this guy, and he liked him, liked who he represented, thought he was representing the kind of people I might fit with. It was so funny, I had to laugh, because okay Joaquim is now bringing me to this guy. And of course, he wants to do it because he thinks I should, and he wants to do it with me because he knows we can and that’s certainly true, and as he says, ‘This is a job of work you could be doing,’ he says, ‘I don’t know why you’re not doing this because everybody else is copying your sound and you’ll end up replicating people who are replicating you…’ And I said, ‘Well, if they pay me okay.’ But of course the big budgets are gone, the narrative films of Walter Hill or Louis Malle, or Tony Richardson. Nobody liked any of these films.

Though, ironically, they’re looked upon differently now, of course.

Anyway, so, it’s different now. TV has no budget and you have to do it all on machines. But we’ll see. Of course, if Walter calls, and he’s got something solid for me to do, knowing me as he does, and I always trusted him, I’d say, ‘Let me try and do it for you.’ On the other hand, films are scary. I got scared in the end. I started getting scared because there was too much I didn’t understand, know how to do. The more you feel you can’t, the more you’re convinced you can’t see, it’s one thing to be young and brave like Mac Rebbenack taking that saxophone gig, a young person will do that, they’ll just say, ‘I’m going to handle it, that’s all.’ But I’m 67 now so I have to say I can’t go on that fear thing. I can’t go on that adrenalin. I have to be able to say, ‘I know what this is, I think I can do it, but I don’t have to turn myself inside out to do it. I don’t want to do that anymore, it’s too hard, it’s too much work.’ But it’s like Joaqium says, you don’t have to work that hard, he can do some of the hard work. It’s so different now with ProTools and all that digital technology. You can do anything. What we used to have to do with tape to make sounds to morph sounds together to go through these insane gyrations to get things. I remember holding an air brush over 10 electric guitars end to end and having the amps in another room and making this drone. It took hours to set that up, what you can do now in minutes with digital sampling, if you see what I’m saying. I used to have a lot of fun doing that, but it takes too long and it’s too hard and it’s too much work and so now to be efficient and be creative as well, the tools are in the hands of the user, you can do bad work or good work, so we can do good work and you can do things with this engineer that I work with and Joaqium works with, called Martin [Pradler]. If you say, ‘Martin, make this do that, push this down, speed it up,’ it’s fabulous. The guy sits there, he’s a genius, and he goes ding-ding-ding-ding-ding and there’s something. So you have a whole new world open to you in terms of creativity and it’s really true. So I think to myself, I’d like to take a shot at this again. It’s good work. I’d like to make some money sometime. They don’t pay you very much, but it’s okay. You do a little work, you get a little money, what’s wrong with that? It’s good. Of course, I like to work with Joaquim, we have a good time together. Its his ability that’s so appealing to me, so we have a good time. So we’re going to try it. If this agent fella says, ‘I’ve got something for you,’ let’s see what it is you’ve got. I’ve told him I can’t do space and I can’t do aliens and I can’t do cops. I can’t do horrible perversions on screen. I get scared easily. That’s another thing. Walter, I trusted him. It wasn’t about fear and loathing like so many of these goddam films are. That’s another big issue for me. I will not score horrible brutality and violence and just out and out perversions just because somebody things the audience will go for it. That to me is bad, that’s bad shit. I don’t do that. I like stories. If you’ve got a good story, let’s do something. That I can do.

RY COODER – SOUNDTRACKS IS AVAILABLE FROM RHINO