As Shaun Ryder turns 60 today, I thought I’d post my encounter with him from 2007.

We met in Nottingham. I remember the interview was scheduled to place on the roof terrace at one of the town’s Travelodges. But Shaun wouldn’t leave the tour bus, which was parked outside the hotel. It took the band’s press officer the best part of two hours to cajole him to come out and do the interview. When he eventually appeared, he was incredibly nervous. I think this was one of the first interviews he’d done straight, and he really struggled at first. But when he warmed up – and showed me his then-brand new teeth – he was perfectly charming.

What I remember, too, is the generosity of everyone else I spoke to for the piece. Peter Hook, Mani and Damon Albarn all spoke warmly and at length about Shaun. But most pertinently, I remember having a 30 minute phone conversation with Tony Wilson, not long before his death. I rang him in hospital and while he evidently had other, far more serious issues to deal with, he still took the time to talk about Shaun and the Mondays.

++++++++

Shaun William Ryder throws back his head and laughs; a great, long dirty cackle, full of mischief, that bubbles and crackles as it shifts the cigarette tar round his lungs.

“Are you fuckin’ trippin’, or what?” He fixes me with a squint. I’ve just asked Shaun whether he’s got any regrets, whether looking back on those long, lost years he spent as a junkie he’s now experiencing any pangs of remorse.

“Regretful? Am I fuck! No chance, no chance,” he lowers his head, runs his hand across his recently shaved scalp. “They were great times. I can’t remember any of them, mind. If you handed me some photographs, I wouldn’t know where I’d been.”

Start spreading the news: Shaun Ryder is straight. He’s tried to clean up before, but never, it seems, with complete success.

“It was methadone I was getting off. I haven’t touched heroin for five years. I took heroin and methadone at the same time for 20 fuckin’ years.”

Are you worried you might fall back off the wagon?

“No chance. Heroin and crack were my poison. I don’t miss any of it. It only took me nearly 40 years. No, sorry, I’m 44. How old was I when I started using? 16? 15? 13? 14?” He sighs and shakes his head. “My memory’s fuckin’ really bad now, really bad, which I’m probably thankful for. I can remember stuff from being under 13, and from 13 onwards, it’s just a fuckin’ blur.”

It’s early evening and we’re sitting on the roof terrace of a Nottingham hotel. Last night, Shaun played his first ever gig straight, at Bristol’s Academy 2; in an hour’s time, the Happy Mondays take the stage at Nottingham’s Rescue Rooms. They’re warm-up gigs for the Coachella festival in America; small, 350 capacity venues to road test material from the Monday’s new album, due in July, that’s probably called Dysfunktional. Shaun doesn’t like playing gigs this intimate. The experience is currently a little too raw for him without the drugs.

“You can see the audience breathing,” he says aghast. “It terrifies me. I don’t mind being straight, it’s cool, but getting on that stage for the first time… Plus the small venues. It never bothers me playing huge venues; it’s not personal, is it? You do a small venue and it’s fuckin’ real, too real.”

And after the gig last night?

“Pals came by I’ve not seen for a long time. We all went out on a club crawl. Got in about seven o’clock this morning. I’ve had about two hours kip.

“I’m not really good with hangovers. I’m terrible, terrible,” he smiles apologetically.

How does working clean compare with working stoned?

“It fuckin’ frightens me to death.”

++++++++

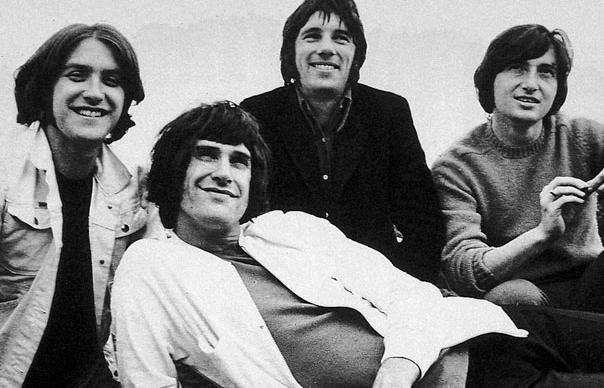

It’s hard to reconcile Shaun Ryder today with the swaggering, leery Shaun of legend. In the late Eighties, the antics of the Mondays were emblematic of a pre-Loaded, pre-Oasis world of hedonism, laddishness and pharmaceutical overload that dovetailed beautifully with the rise of Acid House and Ecstasy. The music the Mondays made – melodies held together with gaffer tape, scuzzy funk grooves topped off by Shaun’s surreal lyrics, rattled out with a brassy, sarcastic sneer – helped defined an era.

“I saw the Happy Mondays at their first, big London gig at the Astoria,” says Damon Albarn, who collaborated with Shaun on Gorillaz’ 2005 single “Dare”. “It was the first time I saw a mass of people turn into a deep ocean.”

“What’s very peculiar about the Mondays,” says former Factory Records boss Tony Wilson, “is that in the 24 Hour Party People movie, the acid house sequence begins with ‘Tart, Tart’, and it works brilliantly. But ‘Tart, Tart’ was on Squirrel & The G Man, the first album [1986]. Those dance rhythms coming over from Chicago and Detroit had already infiltrated Shaun’s consciousness.”

The Mondays music arrived pre-packed with madness and chaos. New Order’s Peter Hook remembers: “They supported us in Glasgow when they were at their naughtiest. While we were onstage, they loaded the rider in the van. They got all the booze – all the fresh fruit, all that bleeding lot – but they couldn’t resist the spotty meat platter. They came back to get it, but the venue manager caught them. He made them unload the whole rider and gave them all a cuff, him and his bouncers. Shaun is incensed by this, gets really pissed off, and he’s sat in the front of a double-wheeled transit they’re driving back to Manchester in, and he kicked the windscreen out. They couldn’t get it fixed, so they had to drive all the way back to Manchester with no windscreen in the van. I suppose our careers have been full of lovable little exchanges like that.”

“In those days, we was lucky to get four cans of lager between us,” laughs Shaun today when I recount Hook’s story to him. “There’s all sorts of stories about me. I’ve stopped listening to them. You’ve got to laugh at them, really…”

All the same, the stories – true or false – increasingly threatened to eclipse the music. While recording their second album, Bummed, in an army town, the band diffuse potential tension with the squaddies barracked there by selling them E. On their first visit to New York, Shaun and Bez are nearly shot leaving a Harlem crack den by a Puerto Rican street gang. Arriving in Rio following a drug-fuelled flight they discover the local press are claiming they were carrying one million E in their luggage. Shaun allegedly poisons 3,000 pigeons in Manchester by feeding them rocks of crack. Dropping his methadone phials at Manchester Airport, Shaun attempts to salvage his supply by filtering the broken glass through a pair of tights. Shaun strips bare Eddy Grant’s Barbados studio to subsidise his blossoming crack habit, rumoured to extend to 30 rocks a day…

“I grew up in New York in the 1970s, and I’ve seen a lot of people who live life on the edge,” explains ex-Talking Head Tina Weymouth, who produced the Monday’s Yes, Please! album. “But I’ve never before seen a group of people who had no idea where the edge is.”

You could hardly call the drug-propelled lunacy of the Mondays unique. But the tales accumulating around them became increasingly murky and more dangerous. Even taking into account the tabloid propensity to exaggerate and embellish, looking back at the Red Top headlines can make for pretty grim reading: “Shaun pulls a gun stunt”, “Pop stars exposed as drug pushers by their own manager”, and worst of all: “Shaun’s death bid.”

++++++++

Did you start using drugs as a form of escape, Shaun?

“I wouldn’t have said that at the time, but yeah. When you’re young, everything’s boring, basically. Of course it’s escaping. For me, it’s all about not feeling it, not giving a fuck, because I’ve got a really big heart. And it didn’t really do to be a caring, thoughtful geezer in this business.”

“Where he comes from, Little Hulton, there’s not a lot going on,” says former Stone Roses bassist Mani, who’s known Shaun since 1987. “We had similar things in my part of town, people getting fucked up because it’s Thatcher’s Britain and there’s nothing else to do. We used to go to the Hacienda and get complete banjoed on whatever substances were around at the time.”

“Drugs never make any record better, they only make making it better,” says Peter Hook. “When you listen to it in the cold light of day, the way normal people do, it’s all a load of bollocks. But it doesn’t stop us doing it. We’re all like pigs in a trough.”

“He’s an interesting person with a good soul,” says Damon Albarn, but: “I understand his subterranean side.”

The trajectory of Shaun’s chemical dependency reached its lowest point a few years back, when he seemed irrevocably damaged by the years of heroin and crack addiction, a busted flush. Watching him on the BBC3 documentary The Agony And The Ecstasy, he resembled a particularly cruel Peter Kaye impersonation of Shaun Ryder; bloated and wheezing, his voice at a weird, unnatural pitch. It was a terrible shock, the final act in the Mondays morality tale.

“He scared the hell out of me looking like death,” remembers Tony Wilson. “I always claimed, when did you last see such an awful white pallor and that viscous, white liquid on top of the skin? And the answer is: Elvis Presley, the last two years. But I’ve learned never to underestimate Shaun.”

It was Shaun’s own decision to clean up for good.

“It was time, I’d had enough,” he says.

When did you decide to get straight?

“About 15 years ago.”

How come it’s taken so long?

“It’s ongoing, innit, really? It’s actually easier than it ever has been before when I’ve tried.”

Why?

“Instead of moping about, I just got on my bike, went cycling with my iPod on. Just kicked myself up the arse.”

What constitutes straight for you? Are you off everything?

Apart from having a drink,” he sloshes some dark liquid round in a little plastic cup. “I’m really conscious about drinking, because the last thing you want to do is replace heroin with booze.”

“I’m not shocked that he’s clean, I’m shocked that he’s remained clean,” the Mondays long-standing drummer, and Shaun’s friend of 25 years, Gary Whelan observes. “You know when people aren’t going to stay off it, anytime they can go back. There’s that story – when you want to stop, you stop. Shaun used to say: ‘One day, I’ll get to that point.’ And he has.”

++++++++

If drugs drove the Mondays back in the day, I want to know what’s driving Shaun now he’s clean – but he’s shy and evasive, almost coy.

“Don’t know, fella. It’s my job, that’s it. I dig being in the studio. I really don’t like doing this [interviews], especially now I’m conscious about what I’m saying. Before, I couldn’t give a fuck. What’s driving me? No idea.”

Tony Wilson is more forthcoming: “Now he’s straight, Shaun is having some relationship with his art for a change,” he tells me. “He doesn’t like talking about that. But maybe, just maybe, he can understand it a bit now. There’s a song called ‘Somebody Else’s Weather’. Who else can contain the whole notion of Global Warming in three words? His lyrical power is unmatched, except by Alex Turner.”

“I’m fucking Barabbas mate,” says Shaun. “I’m the one that got away. I wrote some alright songs, I wrote some alright tunes,” he says, a model of self-deprecation. “It’s pretty easy, there’s nothing clever about it, it’s like writing cartoons. Whatever, taking the piss.”

“There’s a piece in The Independent recently about LS Lowry, talking about why he was never taken seriously,” says Gary Whelan. “It was because he always used to talk himself down, say ‘I’m not a fuckin’ artist, I’m just doing a bit of a doodle.’ It’s our insecure, north Mancunian, blue collar rules – you don’t admit to it, because if you do it’s over.”

“Being a singer when I grew up was for fuckin’ pooves,” claims Shaun. “I got saddled with a job, being a singer, writing lyrics. So I’ve had to do that. Us being in a band was just something to fuckin’ do, really. It was only ever meant for us lot. I didn’t even want to do gigs, I didn’t even want to make a fucking record.”

It’s taken Shaun a phenomenal degree of self-control to get where he is now, and even if he won’t quite admit it on record, he’s extremely proud of his achievement – as are those closest to him.

“He’s a very strong-willed character,” says Mani. “We’ve both had mates that have gone down the death path, but I think Shaun was always that little bit too wise for that.”

“One of the nicest things Shaun ever said about me was: ‘He used to be a cunt, but he’s alright now,'” laughs Peter Hook. “Now I can repay the compliment.”

“Mr Ryder is in his best form, it’s the best I’ve ever known him,” confirms Bez.

Shaun reflects ruefully on some of his previous attempts to get clean, including Naltrexone implants:

“I was one of the first to get them. Fuck me. Fuck that, terrible. You wake up, and you’re supposed to have done your rattle in the sleep. They put you out for 24 hours, induce you. And it’s a fucking nightmare, absolute nightmare.”

Today, despite his hangover, Shaun certainly looks in better shape. He’s slim, though his hands are a little jittery and he sucks hard on cigarettes, deep, lung stretching drags. There’s a new set of teeth courtesy of a “celebrity dentist” that he’s claimed cost £25,000. They’re almost comically white in contrast with Shaun’s sallow, ex-junkie complexion, and Mani notes with a laugh that the first time he saw Shaun with his new gnashers in place he thought he looked like “the mysterious seventh Osmond brother.”

Shaun has what appears to be a solid support network around him at present. Although there’s the apparently never-ending saga of Shaun’s legal wrangles with previous management, he has a pair of new managers, Elliot Rashman and Stuart Worthington. Rashman managed Simply Red before quitting the music industry a decade back. It was seeing the shocking state of Shaun in The Agony And The Ecstasy that made him want to return to music. Something of a philanthropist, perhaps, he describes managing Shaun to me as “voluntary social work”.

“He’s the only cunt who’s given me a really mad bollocking since I was 10 years old,” Shaun says of Rashman with respect verging on awe.

It’s Rashman and Worthington who negotiated the band’s current contract with Sanctuary Records, home to other Manchester luminaries Morrissey, The Fall and the Charlatans.

At the Rescue Rooms gig, the Mondays drop into their set four songs from the new album. The venue is packed, and it’s ridiculously hot, but the Mondays songs – both old and new – are greeted with a mini riot. You’d expect the audience to comprise almost exclusively thirtysomething men, families at home, pills at the ready, out to recapture something from their youth. As it transpires, they’re young, students mostly, experiencing the Mondays magic for the first time, screaming for Shaun and Bez. Shaun stays towards the back of the stage throughout – “I’ve got to get over these nerves,” he’d muttered to me earlier – while Bez does what Shaun calls “his Tigger thing”.

++++++++

Much later, Shaun, Gary and Bez sit upstairs in the tour bus, toasting the gig’s success over a few beers; a far cry, you presume, from the kind of celebrations they’d have indulged in a few years back. They’re the only three members of the original line-up to have made it this far, through the busts and arrests and wild, wild times.

Are you surprised you’ve survived this long?

Gary: “I am.”

Bez: “I’ve got blind faith. I believed in us all the time, 100%.”

Gary: “I never thought we were that good.”

Bez: “No, that’s why it’s good. Cos we was really shit, but we just got better. We couldn’t even play a tune all the same speed all the way through. Remember? We’d start off really slow, get faster in the middle, and really fast at the end.”

Shaun: “In the original band, the guitarist only listened to his guitar, Our Kid [Paul Ryder, his estranged brother] only listened to his bass, the keyboard player only listened to the fuckin’ imaginary messages he was getting from God…”

“The main thing is,” says Bez, “it’s nice to walk on stage knowing you can buzz off some new tunes. I was beginning to fuckin’ dread turning into cabaret. I’m so pleased, because in times of hardship, the Happy Mondays have been our lifeline, and without it we’d have been nothing. It’s the thing what keeps us alive and going.”

Shaun slugs from a cup brimming with Jameson’s and coke and for the second time today stares me straight in the eye.

“Our present is that we’re all still alive, mate.”