The brilliant, frustrating career of the Associates is not short of myths. Summon a Top Of The Pops clip of “Club Country”, their second hit from May 1982, and the captions will suggest that the band used to record with cups of coffee taped to their heads, while “at least one of their songs was recorded in a bath.” Famously, singer Billy MacKenzie, a breeder of champion whippets, kept a hotel room in London for his dogs. He had a Rolls-Royce, because it was good for his voice. Sometimes in hearsay the Rolls-Royce is expanded to a fleet of classic cars, sometimes it’s the burgundy 1962 Mercedes 220 SE convertible the Associates bought as a company car, to save on taxi fares. In truth, bass-player and producer Michael Dempsey was the legal owner of the Merc, and he confirms that MacKenzie did take the wheel once, crashing into a fence.

The symbolism is too obvious. But if the career was a beautiful car crash, what about the wreckage? What about the music? The Associates proper made just two albums and one compilation of experimental singles. MacKenzie kept the name after he and his musical co-conspirator Alan Rankine split in 1982, but the essential work was a result of the supernatural chemistry between the two men, coaxed into its fullest expression with the assistance of Dempsey, who has overseen these reissues, bringing new clarity to the records. (The albums are expanded to double CDs, too, though all but a handful of the extras have been released previously.)

Sulk, we know, is an unfinished cathedral rather than a flawless masterpiece, but it has never sounded better. The sonic approach to that record – start with the hook, throw in the kitchen sink and keep on building – suggests it could have been a victim of the production excesses which have rendered so many 1980s pop records unlistenable. But the Associates were often perverse, always askew. They embraced contradiction. The rhythms sound out of time, even when they aren’t. The tunes are bright, the words are dark.

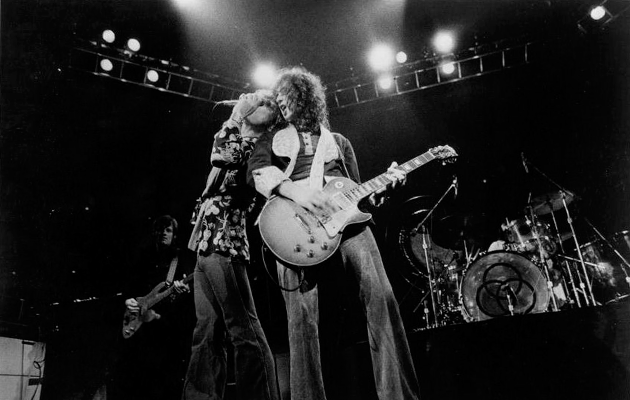

Dempsey suggests now that the Associates weren’t a typical ’80s band, but had more in common with the experimental pop of the ’60s and ’70s. Check the punky cover of Barry Ryan’s grandiose 1968 hit “Eloise”, an early demo. “That was us connecting with all that we loved about ’67, ’68, all these pop records like The Love Affair, ‘Rainbow Valley’ and Paul and Barry Ryan,” says Rankine. “All these big bombastic records – they had big brass, they had big strings, and if it wasn’t Phil Spector, it was still quite a wall of sound.”

Those aspirations may account for the Associates’ ambivalence towards their first album, The Affectionate Punch, which they made twice, somewhat pointlessly. When they announced their arrival with an impudent cover of “Boys Keep Swinging”, their debt to Bowie seemed obvious. The strangeness of their version of the song has grown more pronounced, and Punch no longer sounds like a Bowie tribute. In the light of what was to come, it feels understated, but the components are in place. Musically, it is playful, as Rankine rolls out cinematic soundscapes for MacKenzie’s icy lyrics. It’s all a bit sci-fi (“Logan Time”), gender-fluid (“A Matter Of Gender”, “A”) and quietly compelling. The despair of “Even Dogs In The Wild” is delivered as a finger-snapping torch song with a siren guitar and a whistling solo. What’s most notable, thanks to Dempsey’s studious remastering, is how vibrant it all is.

The group left Fiction after their debut, but stayed on for six months in the flat provided by the label in St John’s Wood, recording singles for Situation Two as a means of keeping afloat in London.

“We had somewhere nice to stay but absolutely no means of getting food, sustenance, nothing,” says Rankine. “So we were going around nicking the milk off Paul McCartney’s doorstep, and nicking the rolls that were left outside the corner shop.” The compilation of those singles, Fourth Drawer Down, is an extraordinary document on which the sense of mystery deepens, and the commitment to sonic experiment becomes more pronounced. “Kitchen Person” is a rolling thundercloud of gloom and exultation within which the flamboyant, charismatic MacKenzie appears to be examining shyness, while Rankine assembles a soundtrack soaked in exotic menace; the manic mood, in this pre-sampling era, was created by playing at half-speed and then running the tape at full-tilt. “Tell Me Easter’s On Friday” is a stumbling, extraordinary procession, and there is no obvious comparison to the song’s marriage of Rankine’s far eastern motifs and MacKenzie’s shower-stall croon, but you can just about detect a thematic empathy with Joy Division. But “Easter” is followed by the instrumental, “The Associate”, which is like the theme to a non-existent ’60s spy thriller. So that would be Joy Division channelling John Barry in outer space.

Then there is Sulk, on which the group’s splendour is fully realised. It is ornate, unsettling, joyous and playful. For years, Dempsey worried it had become unlistenable, thanks to unsympathetic mastering. “You’d take it into the master room, and the guy looks at his meter and goes white; he doesn’t know what to do with it, and usually he would err on the side of caution.”

Caution now safely abandoned in the remastering suite, Sulk is revealed as a glorious tapestry of sherbet and fizz. Rankine is clearly in his element, piloting a journey into sound, and MacKenzie has settled into his role as a purveyor of intrigue. They have the cheek to rework the cursed suicide song “Gloomy Sunday” as an electronic croon (and get away with it), but nothing compares to “Party Fears Two”, which is that contradictory thing, an anthem of ambiguity. It’s about emotional dread, or nervous breakdown, or fear of commitment, or something, and it sounds like pure joy; almost as if, for Alan Rankine and Billy MacKenzie, the glorious anxiety of pop music was a way of making beauty out of doubt.

EXTRAS 7/10: Each album has second CD of rarities. Sulk has five previously unreleased tracks, including two produced by John Leckie. Sulk is also available on 180g vinyl.

Q&A

Alan Rankine and Michael Dempsey

What were your impressions on first meeting Billy MacKenzie?

ALAN RANKINE: I heard him a couple of weeks before I met him. He was a diffident character. Quite aloof. He seemed like a fish out of water. Coming from Dundee to Edinburgh he was quite self-preserving until I got to know him a bit better, but that took place over just a couple of days.

MICHAEL DEMPSEY: I half-joined while I was in the Cure. The Cure were on the same label, Fiction, so we’d meet in the bar at Morgan Studios. I also remember meeting them up in Edinburgh, though I can’t see how. I remember meeting them in a bedsit, and sitting round a Dansette record player, with Chris Parry, the Cure’s manager. The Cure were there as well, Robert and Lol, and we were listening to the record the they made, Boys Keep Swinging. Straight away I was impressed.

RANKINE: I remember when Bill came down to Edinburgh. I had a flat I was sharing with my girlfriend – and Bill had to stay where the rest of the band was staying. He came to me after two days, and he said, “Man you’ve got to get me out of here, I cannae take it any more, there’s too much testosterone.” Within two days, Bill was sleeping on the couch in the lounge, and we were listening to Giorgio Moroder and the Munich Machine. So we were absorbing all of that, and Low and Heroes, and the stuff that was happening with Eno and Fripp. Bill and I had so many things to draw on. We loved the cinematic stuff. We loved the way that you could play with people’s emotions. At the same time there was a pop sensibility. Bill and I used to warm up in the studio and we’d do “Let’s Spend The Night Together” by the Stones, or “Brown Sugar”, and Bill would be camping it up, and suddenly we’d just shift and we’d be doing “The Look Of Love” and Bill would be imitating Dusty Springfield.

What was the balance of power in the studio?

DEMPSEY: I never saw Bill and Alan disagree about doing anything. They had an instinctive understanding. Billy would hum whatever he wanted, and within a couple of seconds, Alan would be barking out the chords.

Were you under pressure to have hits?

RANKINE: There was no pressure. “Party Fears Two”, the bulk of that was written back in ’77. But we knew we couldn’t use it in ’77. Nor ’78. Nor ’79. it would have just been a waste. We had to wait until the time was right. Even when it came out it didn’t sound like anything! All of it is just slightly askew. It’s slightly unsettling, but somehow it draws you in. Listen to “Club Country”: “The fault is, I can find no fault in you” as an opening line, and then as the closing line of the chorus: “Every breath you breathe belongs to someone there.” That is quite dark. This is us not wanting to play the game. This is us not wanting to suck on the cheesy foreskin of corporate rock.

The singles on Fourth Drawer Down had an experimental quality.

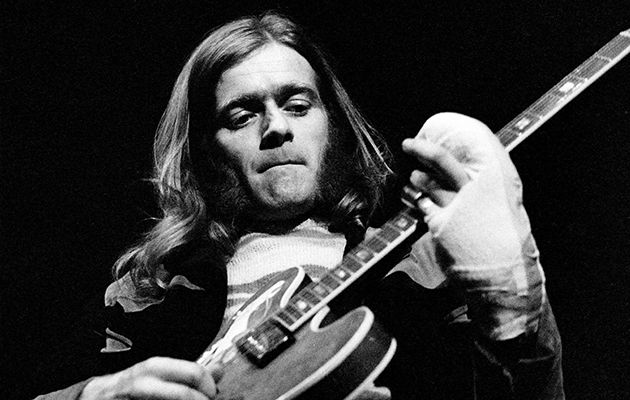

RANKINE: We were recording stuff like “Tell Me Easter’s On Friday” and “Q Quarters” from 9pm on a Sunday evening, to 9am on a Monday morning. That seemed to bring out this kind of dark quality in the music. On “Message Oblique Speech” and “White Car In Germany” I’m using a water-filled balloon on the strings. It always seemed to me that feedback, if you could control it, was good, but every time you got a good note you had to stop the string in order to get a different note. And this was a way of not stopping the string, you could just roll the balloon around. I would call it “tit speed”. It’s like when you stick your hand out the window of a car and you’re going between 55 and 65 miles an hour and you clutch the air. That’s tit speed. It’s the only way I can explain it. It’s like a really nice tit.

Did Billy want success? He seemed to work hard to undermine it.

RANKINE: Bill liked the good things in life. I just think he wanted it on his terms. But there were aspects of it that didn’t sit well with him. Like having to do the things you have to do.

DEMPSEY: Bill came from another planet. But he named the band the Associates for a very good reason – he told me this – because he liked the free-flowing association of people. He got bored quickly. He wanted to do the opposite of what was expected of him. He was contrary. That makes life difficult, but it makes for good art.

INTERVIEWS BY ALASTAIR McKAY

The July 2016 issue of Uncut is now on sale in the UK – featuring our cover story on Prince, plus Carole King, Paul Simon, case/lang/viers, Laurie Anderson, 10CC, Wilko Johnson, Bob Dylan, Neil Young, Steve Gunn, Ryan Adams, Lift To Experience, David Bowie and more plus 40 pages of reviews and our free 15-track CD

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.