“What does magic mean to me?” wonders an indomitable Genesis P-Orridge, puffing on the oxygen tubes that sprout from h/er reconstructed nose at the start of David Charles Rodrigues’ loving, curious, partial documentary. “The only real answer to any question you have is: the sum total of my life so far.”

S/he Is Still Her/e doesn’t quite give us that sum total, and feels very much like the authorised story (a large part of it is told by h/er delightfully nonchalant Californian daughters, Genesse and Caresse). But then any proper reckoning with this queer, relentless, experimental life might run to several hours, in many media and be seized by police in most countries.

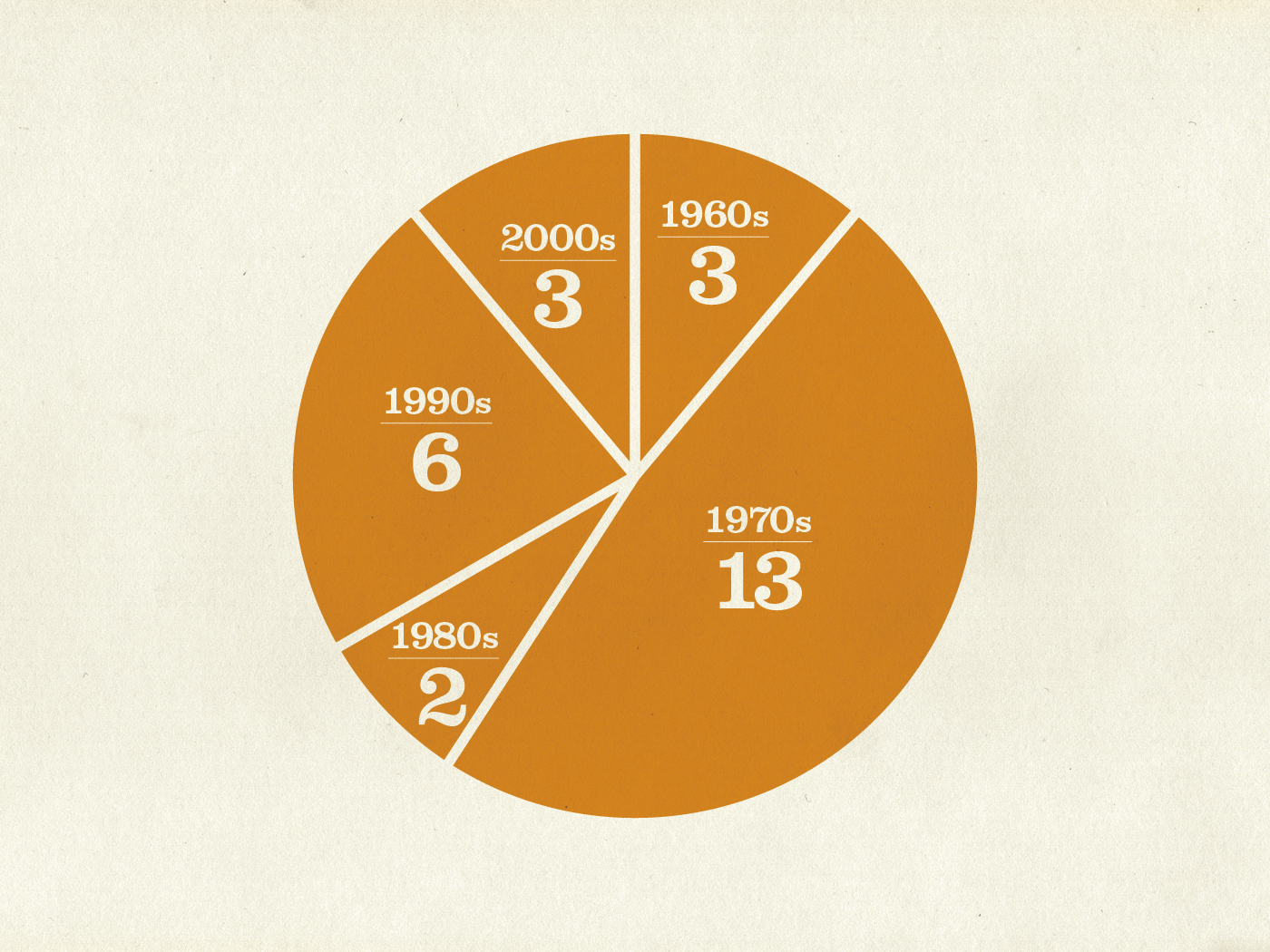

In some ways, Rodrigues gives us the fairy story: how a sickly, sullen boy from Middle England heard voices in the hedgerows, dived headlong into the 1970s transgressive art scene and eventually, through the power of unconditional love, transformed themselves into a fabulous pandrogynous international art monster.

It includes various fairy godmothers and fathers (notably William Burroughs who, over a couple of bottles of whisky, advises the young GPO that “your job is to learn how to short-circuit control”), some very wicked witches (the police, censors and politicians who eventually force the P-Orridge family to flee to California in the early ’90s) and a string of beautiful princesses – Cosey Fanni Tutti, Paula Brooking and finally Jaye Breyer, who Gen seems to perceive as Blakean emanations of some primal goddess, Cosmosis.

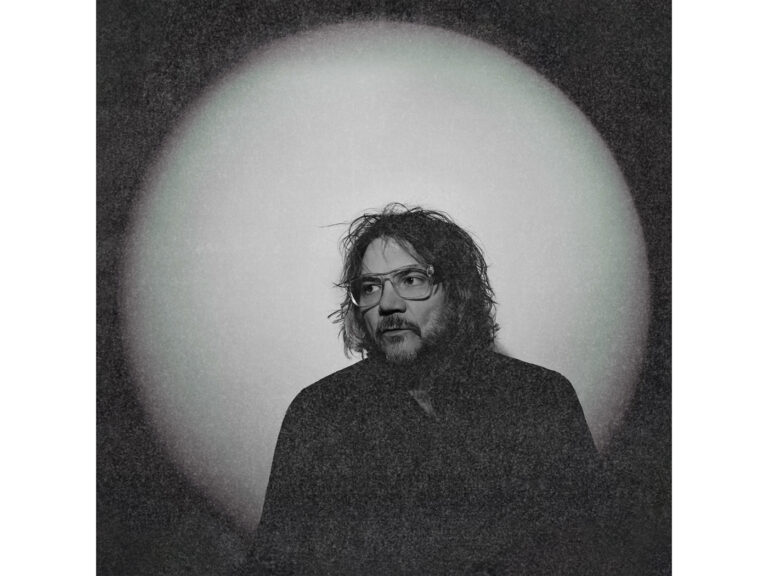

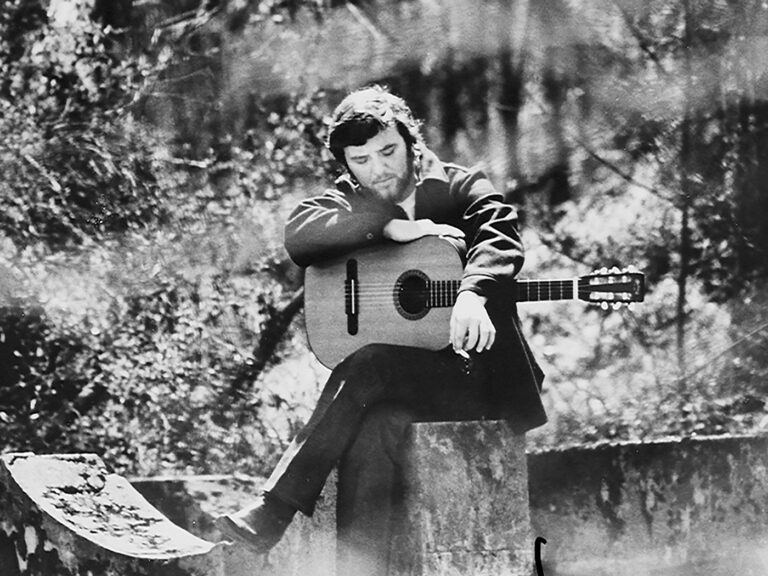

The film is based on a series of interviews that Rodrigues conducted in the last months of h/er life, as GPO was ailing with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. We see h/er holding court in New York, still funny, philosophical and topless, as s/he sits for one last portrait. “The body is a cheap suitcase for consciousness,” s/he proclaims, telling the story as the camera and paintbrush roams over every tattoo and scar, the stickers the vessel has collected on its manifold travels through time, space and more psychic realms.

As the pendulous breasts and fulsome lips indicate, the suitcase is in fact not so cheap, having been the recipient of the better part of half a million dollars in cosmetic surgery (thanks largely, we discover, to a lawsuit against Rick Rubin, following a fire at the producer’s LA mansion). There is something unearthly, uncanny about h/er presence – part Sea Witch, part Marianne Faithfull, part (in Morrissey’s words) “nightmare teenager of 70”, and Rodrigues’ film has the distinct feel of a hagiography: the life and times of a latter-day post-gender saint.

The disparity between the loving, compassionate philosophy GPO espoused, and the brutal, industrial forms this sometimes took in h/er art and life comes to a head when the film covers the Throbbing Gristle years. One-time COUM member Les Maull tells of GPO’s frightening temper and tantrums. For a couple of minutes, this relentless, flickering film goes silent and dark, and onscreen text says: “In a 2017 memoir Cosey accused Genesis of controlling aggressive behaviour. Genesis denied all accusations. Cosey politely declined to comment.”

The refusal certainly feels pointed and is a sickening abyss in the story, but the film proceeds regardless, heading onwards through the ’80s of Psychic TV, the north Californian rave ’90s and the 21st-century renaissance, where in an East Side BDSM dungeon, Gen meets the funny, charming dominatrix Lady Jaye, the muse and love s/he had been always searching for.

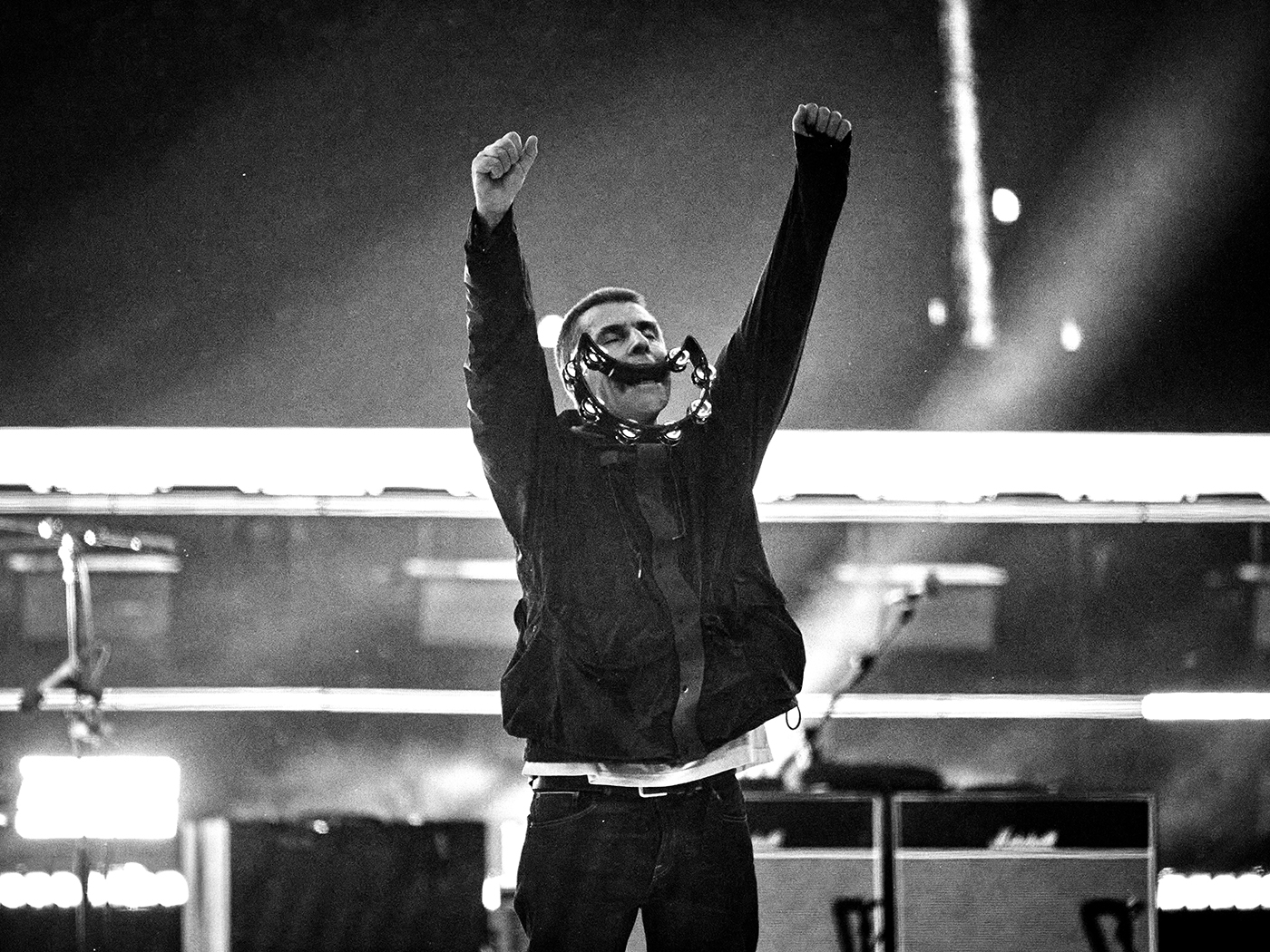

There are other more detailed investigations of the “magic approach to sound” of COUM and Throbbing Gristle (notably the 2020 BBC oral history Other, Like Me), but as a portrait of a unique, unrepeatable individual this is hard to beat. In a paradox Gen might have enjoyed, it is ultimately touching: detailing a very charmed life where every disaster – exile, imprisonment, life-threatening injury – is somehow turned to advantage, and our hero/ine persistently escapes certain doom to land magically on their feet. As our leaders diminish our liberties daily, this relentless dedication to a life lived experimentally and without fear feels particularly and profoundly timely.

For info on the latest screenings of S/he Is Still Her/e, visit the Doc’N Roll site