When Blake Mills released his debut solo album Break Mirrors in 2010, he admitted it was essentially a calling card to get more session work. Given that he’s since been handpicked to play with both Bob Dylan and Joni Mitchell – not to mention Jenny Lewis, Randy Newman, Norah Jones and a zillion others – you have to say that it worked. Mills is primarily in demand as a highly skilled and intuitive guitarist, but he’s one of those musicians who can play anything: harmonium on Rough & Rowdy Ways, drums on Feist’s Multitudes. He’s also a producer and co-writer, with his fingerprints all over recent albums by Laura Marling, Perfume Genius and Marcus Mumford.

Yet despite his ubiquity, Mills remains something of an enigma. Often when a sideman steps out of the shadows, it’s because they want their own voice to be heard; but this is Mills’ fifth solo album, and with each one he seems to become ever more elusive. 2021’s Notes With Attachments, a collaboration with Pino Palladino, was very cool but almost mischievously slight, the two seasoned sessioneers competing to see who could disappear most effectively into the music.

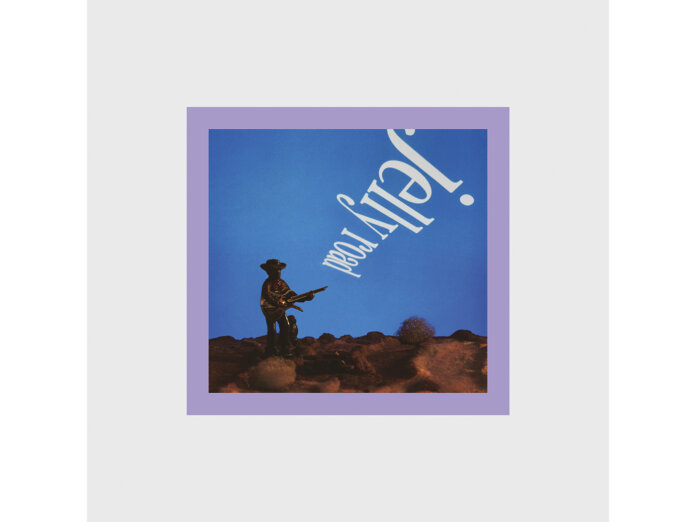

In another confounding move, Jelly Road was largely written and recorded with the relatively unknown Chris Weisman. Presumably Mills could have called in any number of celebrity pals – and some of them do make cameo appearances here – but Weisman has been plucked from the obscurity of Vermont, where he’s stealthily amassed a vast catalogue of eccentric, home-recorded albums. Dipping into Weisman’s Bandcamp archive, you can hear why Mills spotted a kindred spirit; both men balance a respect for classic songcraft with an urge to subvert it at every opportunity.

Jelly Road presents itself as a live ‘in the room’ record while quickly screwing with that perception. It starts with Mills whispering the title of “Suchlike Horses” as though it’s a raw campfire demo, acoustic guitars fumbling around in search of a tune. But then his vocal beams in from another dimension entirely, slathered in warm space-echo. The acoustic guitars disappear, replaced by electric piano and tinkling cosmic synths. It’s as if he’s pulled a green-screen trick on your ears.

The album is full of these aural optical illusions. Guitars are strung upside-down, or run backwards. The Revolution’s Wendy Melvoin wanders in to sing backing vocals or play wah-wah guitar – but not on the song called “Wendy Melvoin”, which instead foregrounds Mills’ lugubrious harmonica and the bizarre but addictive squawking of Sam Gendel’s contrabass recorder.

It’s clever, but not too clever. Mills and Weisman are careful never to overdo it and obscure the song itself. Moreover, each individual part seems to be invested with its own hefty emotional charge. Take the haywire guitar solo on the slow, quasi-anthemic “Skeleton Is Walking”, played by Mills on his fretless sustainer guitar, and cited as a pivotal moment in the creation of the album. While the lyrics are fearful and unsure, the solo explodes like a dam bursting. As Mills observes, “It says a lot of things that the singer can’t say. And for that reason, it feels very cathartic.”

You can file Jelly Road alongside Dirty Projectors’ Swing Lo Magellan and those recent Bon Iver albums, where Justin Vernon successfully deconstructed his approach without sacrificing any emotional impact. Mills shares with Vernon a love of ’80s synths and guitar tones previously considered taboo by the folk-rock crowd, skilfully combining them with more traditional acoustic sounds to create an alternate timeline where John Prine hung out at Paisley Park.

Just as with the music, Mills’ lyrics toy with the tropes of rootsy American songwriting while simultaneously unpicking them. There are horses and moons and highways, but there are also metaphysical quandaries and “futuristic hellscapes”. He may seem to write in proverbs and koans, but his elegant, oblique style only makes the break-up described in “Jelly Road” all the more poignant: “The dinosaurs were happy, up until they froze/Though we’ve had some good times, this is what we chose”.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given his advanced studio tan, several of the songs appear to be about songwriting itself. “What can make a song unbearable?” Mills ponders on “Unsingable”. “What’s dignified? What’s just a pose?” Yet obviously it’s a song about life, too: the little choices we make every day that mould us into who we are. Whatever this album may or may not reveal about the real Blake Mills, he’s evidently a person who cares deeply – even obsessively – about his chosen artform, and its ability to delight, console and transform. Jelly Road regularly does all three.