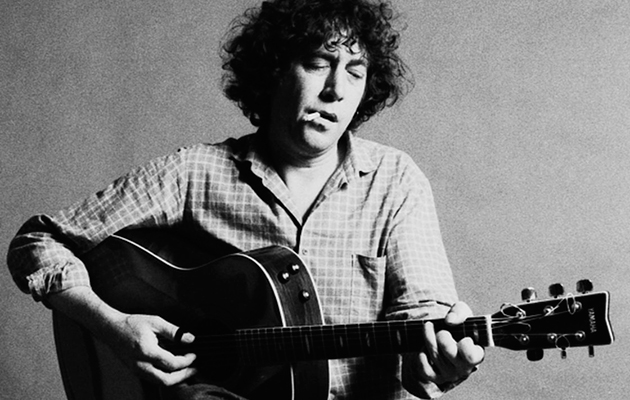

“To address another human was one thing, but a singing voice was capable of so much more,” writes Chrissie Hynde in her fascinating 2015 memoir, Reckless. “Romance made you weak and love was about suffering. I wanted what the jazz musicians were looking for: the supreme. I wanted my voice to take life by the throat and rattle it until it made sense.”

It’s easy to forget what a wonderful instrument Hynde’s voice is. Within a deliberately restricted range, it’s a voice that sighs and swoops, flirts and rebuffs, sneers and charms. And Alone – Hynde’s 12th Pretenders album – is filled with tremendous vocal performances. The title track, the first of three urgent, punky songs that kick off the album, is a celebration of the independent life that switches between swaggering sung phrases (“Nobody tells me I can’t/Nobody tells me I shan’t”) and spoken-word beat poetry (“life’s a canvas and I’m on it!”). On “Blue Eyed Sky” the lovelorn lyrics tumble out of her arrhythmically, like Dylan. On the ballads, Hynde’s smoky contralto glides lazily up to the correct tone and then swoops down at the end of each phrase, rather like the saxophonist Coleman Hawkins. It’s a virtuoso performance.

The album was going to be credited to Chrissie Hynde alone, the follow-up to her 2014 solo debut Stockholm. Where Stockholm was recorded with Swedish pop producer Björn Yttling and veered towards machine-tooled Swedish pop, Alone has the feel of the first three Pretenders albums – all chiming guitars, Phil Spector drum stomps and creaky vintage studio details. “It felt like the gang was back,” says Hynde. “It made sense to use the Pretenders name for this album.”

Since the death of guitarist James Honeyman Scott in 1982 and bassist Pete Farndon in 1983, the Pretenders has been a pretty nebulous concept. Drummer Martin Chambers, the other founder member, is part of the current touring band but he hasn’t played on a Pretenders album since 2002’s Loose Screw. Alone – like most Pretenders albums – is pretty much Hynde with hired hands.

The most important hired hand here is producer Dan Auerbach, the frontman of the Black Keys, Grammy-winning producer and, like Hynde, a native of Akron, Ohio. Auerbach has worked his sonic magic on a varied cast of American pop heroes, from Dr John to Lana Del Ray, from Lee Fields to Ray LaMontagne. On Alone, Auerbach enlists as a backing band his side-project The Arcs (including drummer and multi-instrumentalist Richard Swift) along with twangy country rock guitarist Kenny Vaughan and Johnny Cash’s bass player Dave Roe.

There’s always been a slight, natural wobble in Hynde’s voice. Tracey Thorn, in her excellent book on the art of singing, Naked At The Albert Hall, compares Hynde’s natural vibrato to the tremolo setting on a guitar amp. One reason why Auerbach seems like Hynde’s most simpatico producer since Chris Thomas is because his work is imbued by that heavily tremolo’d sound, and it’s certainly all over this album.

On the second track, a rambunctious tribute to her backline technicians called “Roadie Man” is transformed from chugging 12-bar blues by some shimmering guitar riffs. On the rumba-tinged “One More Day”, the antique Cuban guitar patterns provide the perfect counterpoint as Hynde spins out extemporised riffs at the upper end of her range. On “The Man You Are”, a woozy guitar provides a deliciously off-kilter countermelody to Hynde’s sighing, unromantically romantic vocal. On “I Hate Myself”, the tremolo’d guitars mesh with the Spectorised drums as Hynde spills out one of her hymns to masochism. On the dramatic “Never Be Together”, the tremolo guitar is provided by none other than Duane Eddy himself.

Best of all might be the album’s closing ballad, “Death Is Not Enough”. It’s the one song not written by Hynde herself: it was initially written by her friend Marek Rymaszewski as a string-drenched miniature. But, in the same way that she transformed Ray Davies’ “I Go To Sleep”, Hynde completely owns this song, recreating it as a heart-stopping power ballad that could provide the sensational climax to a funeral. starts with a celebration of loneliness and ends with a celebration of death. It’s a wonderfully bloody-minded riposte to the clichés of rock’n’roll from one of the genre’s undersung greats.

Q&A

Chrissie Hynde

How did you hook up with Dan Auerbach?

It wasn’t really that we both came from Akron – I bailed out of that place years ago! – although I had actually met Dan’s dad there once! It was more that I had admired the Black Keys from afar and I liked the guy. I mean, you can tell a lot about a musician by the way he holds his guitar. You really can tell if he *gets* rock’n’roll music!

How did he change the way you worked?

He’s half my age but seems older than me! He sits in his studio surrounded by vintage recording equipment, old sculptures and Nudey suits, listening to obscure, crackly old records. He works fast – we recorded this in two weeks. I wrote most of these songs on my own – most of them are autobiographical – but Dan would always come up with wonderful textures and sound effects and guitar riffs, to the point where he gets a co-credit on some of them. The role of a guitarist is always to set up a singer, like a footballer providing an assist, setting up a goal. Dan’s great at setting me up.

What’s the difference between a Pretenders album and a Chrissie Hynde solo one?

If I’m completely honest, nothing! I mean, I lost my guitarist and bass player in 1982, 1983, and I was pretty traumatised by that. I soldiered on using the Pretenders name and insisted it was always a band, but I guess it was always just me all along! This started out as a solo album – in fact a couple of songs are co-written with Björn Yttling, the producer on my last album, Stockholm – but none of my records are solo albums. I need to be surrounded by a band, a gang.

Did writing your memoir last year, Reckless, rekindle your punky enthusiasm?

Possibly. But an autobiography is more about getting stuff off your chest. For a few years I had been sinking into a depression. Grammy culture has swallowed up everything I love about rock’n’roll. It’s now the establishment, it’s stadium pop, it’s mainstream, or it’s wimpy vagina rock. Now I think bands are back. That thrill of picking up a guitar or bashing a drum kit when you’re 16, you can’t beat it. What writing Reckless reminded me is that, if you’re a rock’n’roll figure, you don’t change. Lemmy couldn’t retire from being Lemmy. He was Lemmy until the end. I mean, I talk to John McEnroe about this – if you’re a sportsperson, you work like a dog for a few years and, by 35, you gotta find something else to do. People in rock’n’roll have a duty be themselves. I’m 65 and I’ve barely changed since I was 17!

INTERVIEW: JOHN LEWIS

The December 2016 issue of Uncut is now on sale in the UK – featuring our cover story on Pink Floyd, plus a free CD compiled by Lambchop’s Kurt Wagner that includes tracks by Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds, Sleaford Mods, Yo La Tengo, Can. Elsewhere in the issue, there’s TheDamned, Julia Holter, Desert Trip, Midlake, C86, David Pajo, Nils Frahm and the New Classical, David Bowie, Tim Buckley, REM, Norah Jones, Morphine, The Pretenders and more plus 140 reviews