This oral history of the Rolling Thunder Revue that first appeared in Uncut’s June 2019 issue.

Welcome, then, to the Rolling Thunder Revue –

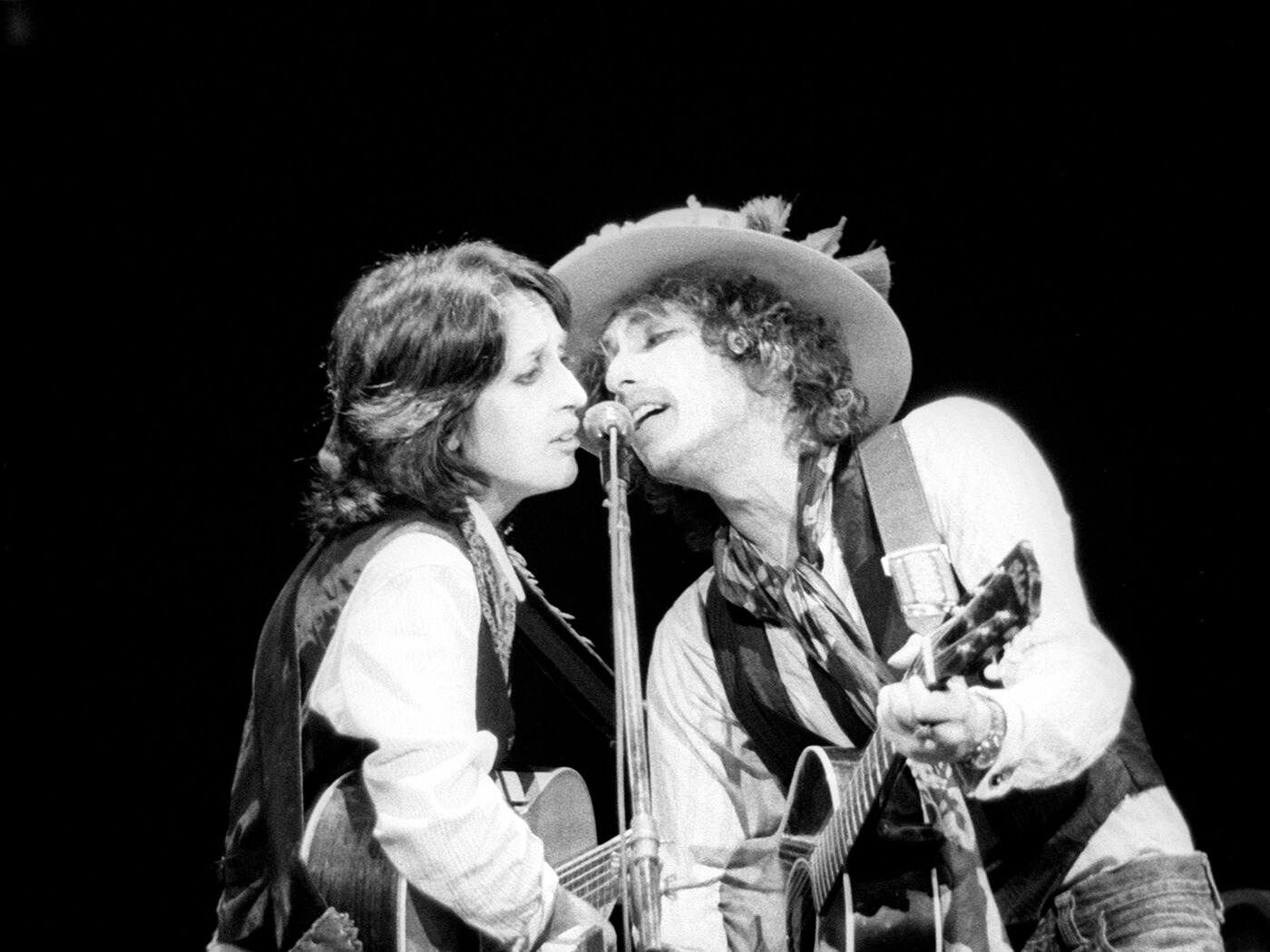

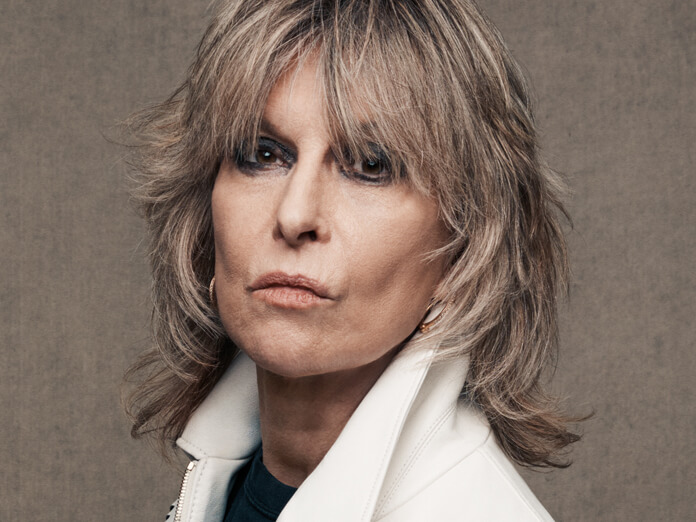

Bob Dylan‘s colourful charabanc that wound its way across America during 1975 and 1976. Peter Watts talks to tour insiders and hears tall tales involving doppelgangers, Beat poets and mysterious shamen. “It was extraordinary,” recalls Joan Baez. “You just wanted to be there.”

In 1974, Bob Dylan decided, not for the first time, he wanted to do something different – only he wasn’t entirely sure exactly what. After his successful comeback tour with The Band and the acclaim of Blood On The Tracks, he could have pursued a lucrative, conventional touring model. Instead, he envisaged “something like

a circus,” he explained to his friend Roger McGuinn. From such a loose idea, however, emerged something entirely unique: a free-wheeling, multi-artist caravan – the Rolling Thunder Revue – that began in October 1975 and finished up in May 1976.

The Rolling Thunder Revue was conceived in the folk venues of Greenwich Village and took Dylan and friends around the small towns of New England and Canada. Liberated, Dylan wore hats, scarves and flowers and sometimes performed in masks or whiteface. Venues were town halls and civic centres, where the players often arrived

with hardly any notice. Shows lasted four hours

– sometimes two sets a day – and culminated in mass singalongs of “This Land Is Our Land” or “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door”.

The tour mixed old friends – McGuinn, Joan Baez, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Bob Neuwirth –

with new faces like bassist Rob Stoner, multi-instrumentalist David Mansfield, violinist Scarlet Rivera and singer Ronee Blakley. There were wild cards like Mick Ronson, Allen Ginsberg and T-Bone Burnett, guest appearances from Robbie Robertson, David Blue, Arlo Guthrie, Kinky Friedman, Gordon Lightfoot and Ronnie Hawkins. Joni Mitchell played one show in New Haven and enjoyed it so much, she joined the tour.

At the same time, Dylan was making Renaldo

& Clara – with playwright Sam Shepard as the nominal screenwriter – shooting concert footage alongside largely improvised scenes like Dylan’s visit to Jack Kerouac’s grave with Ginsberg. The first leg culminated with a benefit show for imprisoned boxer Rubin “Hurricane” Carter at Madison Square Garden on December 8.

A second leg took place in spring 1976 but didn’t have the spirit that made Rolling Thunder such a blast for performers and audiences alike. “There was so much music on that tour,” recalls Larry “Ratso” Sloman, the Rolling Stone reporter who wrote a book about his experiences, On The Road With Bob Dylan. “Music in the hallways of the motels, in the motel rooms, in tour buses, in the dressing rooms, the hospitality suite. People were jamming all night and then poured into the bus for the next show.”

“He wanted to do something different”

Ideas percolate over baseball in Malibu and in the Greenwich Village folk clubs

JOAN BAEZ: I knew it would be a great thing to do. My main memory is sitting in the audience every night to see Bob. The first leg was colourful and beautiful. There was a lot of insanity, and Bob filming it, and people I knew, and people I didn’t know, like a floating ship of crazies.

ROGER McGUINN: Bob came over to my house in Malibu one day. There was a basketball hoop over the carport and we played one and one. At one point, he said he wanted to do something different. If Bob says he wants to do something it could be, “Let’s all go to Mars”, something wild and crazy. He said, “I don’t know, something like a circus.” Then we went back to basketball. He won because he’s much better than I am.

LOUIE KEMP: I was a businessman in the commercial fish process in Alaska. Bob and I were friends since we were 11. We were hanging out in LA as he got ready to go on tour in ’74 with The Band. He asked me if I wanted to come. That gave me an insight into how the tour business worked. Eighteen months later we were in Minnesota. He had this idea for a tour, but the promoters kept discouraging him because it wasn’t commercial. He wanted to do something more down to earth that would be fun for the audiences and bands. He didn’t care if he made any money, he wanted to have fun,

play some cool places like a musical gypsy caravan. Everybody told him it wouldn’t work, but I thought it was a great idea. He said do I want to produce it. I agreed.

RAMBLIN’ JACK ELLIOTT: I was playing in a club in Greenwich Village, The Other End or The Bitter End, they were always changing the name, and Bob showed up. Patti Smith sang solo, Bob sang a few songs and at the end, Bob said he was thinking of doing a little tour playing small halls with Joan Baez and would I be interested. I said count me in.

SCARLET RIVERA: I dropped out of Southern Illinois University and bought a one-way ticket to New York.

I had an idea I was going to integrate the violin into contemporary music and fate made it happen. I was walking in the East Village with my violin case over

my shoulder when a nondescript green car pulled alongside me. A guy that looked like Bob Dylan rolled down the window to ask, “Could I play that thing?”

I was about to cross the street when Dylan saw me. If

I had crossed one minute before he’d never have seen

me at all – although we connected in such a deep way,

I think it was inevitable.

LARRY “RATSO” SLOMAN: I was in Gerde’s Folk City with Roger McGuinn. We heard Dylan was at The Other End, so we walked over. Dylan was at this big table at the back. He said, “Roger, come on the road with us, we are doing an incredible thing.” And he said I should come and write about it for Rolling Stone.

KEMP: We asked Barry Imhoff, Bill Graham’s ex-partner, to be tour director. We mapped out a tour of the north-eastern states but we didn’t tell the venues who the principal performers were, we just told them it was the Rolling Thunder Revue. Then we’d break the concerts a day before, so people would wake up and hear that Bob Dylan was in town. We didn’t tell the artists where we were going, either. We wanted it to be mysterious and fun for everybody.

ELLIOTT: We started in New England, then went up to Canada and then back to New York for the Night Of The Hurricane at the Garden.

SLOMAN: This was a way for Bob to get back to his roots and bring some of those people like Joan and Jack who were meaningful to his early career.

“The spirit was new…”

Rehearsals begin in October in New York’s SIR studio. The first night of the tour takes place at Plymouth’s tiny War Memorial Auditorium

ROB STONER: I was bandleader. Every night after rehearsal, I listened to cassettes and made notes about what could be improved. I realised we’d be under a microscope. This was Dylan’s new effort and everyone would compare us to The Band. A hard act to follow.

SLOMAN: They had a solid base – Howie Wyeth on drums, Rob Stoner on bass. They could play any sort of music. Then there was T-Bone Burnett and Steven Soles and Mick [Ronson] from Hull.

I don’t know how Ronson happened, I think it was through Neuwirth. He was the nicest guy, sweet and unpretentious.

STONER: We had these figures from his past, but I was trying real hard to guard against it being a museum piece. I wanted it to sound like contemporary arena rock music du jour. Mick Ronson was a great element. He kept it from sounding too folky, and David Mansfield’s versatility was very important.

I tried to arrange the tunes so they didn’t sound mouldy. Fortunately I had Howie Wyeth and also Luther Rix, both very versatile drummers.

BAEZ: This was fresh and way evolved from the coffee houses of the ’60s. The spirit and the music was new.

It didn’t feel like the old days in the Village. It was important that it wasn’t trying to repeat the past. It was extraordinary and out of the ordinary and just crazy enough that you wanted to be there.

SLOMAN: The first night was at Plymouth’s tiny War Memorial Auditorium on October 30, 1975. They were staying at a hotel that was hosting a Jewish women’s retreat. They played some songs and Ginsberg did a reading for a crowd of blue-haired elderly Jewish women.

ELLIOTT: They didn’t understand what we were singing about but they smiled and clapped. Not the best audience.

SLOMAN: It was a little old hall, but there was an electricity in the air. The second night was Halloween and Bob and Neuwirth came out in these masks to sing “When I Paint My Masterpiece”. People were astonished to see Bob in such an intimate setting. It was a thrill to be that close.

STONER: To get the crowd warmed up, the people in the band who were experienced as frontmen or songwriters each got a song. Neuwirth did a tune, I did a tune, Ronson did a tune, Soles did a tune. We were a self-contained opening act. Then we’d bring out the guest artists. McGuinn did his hits, Ramblin’ Jack would do some tunes and then to take it home for the first half, Bob would come out. We’d ease into that with him and Neuwirth singing “…Masterpiece” together in funny masks. Then there’d be 30 minutes of Bob before an intermission. Then we’d have Bob and Joan, then Joan, then Bob on his own. Then there was the grand finale with everybody on stage. We had so many arrows in the quiver.

SLOMAN: Jacques Levy was writing lyrics and he was a great stage director, so he put together the whole format.

RIVERA: Backstage on opening night there is a photo

of Bob kneeling down in front of me with his guitar. Bob was sensitive to the fact I’d never played in front of that many people and I was nervous. He offered reassuring words so I could go out and deliver with confidence.

ELLIOTT: I’d play the last two songs of my set with T-Bone Burnett’s guitar. He was in the band that played behind Bob, they were called Guam. I played solo for about three songs, then Guam came and joined me for two hotter numbers. I did my set early in the show and then as I ran off Bob would run on and say, [does Dylan impression] “Good set, Jack.” Then he’d go on without announcement.

BAEZ: I’m limited in this sort of situation as I do covers, not hits.

I did “Diamonds And Rust” and whatever I felt would get through. Bob was always respectful and introduced me in a polite way, but I felt a little like I did at Live Aid – “What am I doing here?” I had to find ways to keep people amused. I’d go out and dance.

RIVERA: I was fearful of so many people staring at me, so I put

on dark glasses and painted a talisman of protection on myself. That was the beginning of the white face. I sometimes appeared with a painting on my face of butterfly wings or spider web. Bob started wearing the whiteface and I feel certain he understood

the symbolism behind what I was painting.

“He had these prescription sunglasses…”

An unconventional blessing ceremony takes place. Frank Zappa’s tour bus is requisitioned. A young musician shows his appreciation

ELLIOTT: Bob never told us why it was called Rolling Thunder and I never asked. He just thought it was a good name. A friend of mine, a Native American medicine man from Nevada, was called Rolling Thunder. I asked Bob if he knew there was a Native American called Rolling Thunder. He said, “No, I didn’t know that.”

That’s what Bob always says if you ever ask him any question in the world. He always says, “No, I didn’t know that.” When we were staying in Newport, Rhode Island, we all went down to the beach and Rolling Thunder lit

a bonfire. We took turns to say a prayer and he blessed the tour with an eagle feather.

McGUINN: We danced around singing, “Yeah Yeah Yeah Yeah Coco Baby Bop Dooap Bop Dooap,” and it felt good.

I said later that it saved my soul.

BAEZ: I felt Bob wasn’t entirely comfortable with the ceremony. Bob sang his song in that way he has where he wants to get rid of it.

McGUINN: We had this tour bus we rented from Frank Zappa. It had “Phydeaux” – Fido – written on the side and a picture of a greyhound. Bob was in “the green machine”, a GMC motorhome. One time I went with him. He had prescription sunglasses and it was getting dark and he couldn’t see where he was going. That was

a real interesting experience.

SLOMAN: I was in a rental car. Management were always fucking around with me. At one point in New Haven they actually pulled some wires in my car so the battery wouldn’t work. They were sabotaging me. They even discussed getting me a ticket and putting me on a steamer, but I don’t think they had the balls

to do that.

ELLIOTT: Joni Mitchell performed

a couple of shows, and then she came and joined us.

McGUINN: Joni likes to sit up front behind the driver. She had a book, a speckled exercise book, and she was always writing songs. One day I got a song from her, “Dreamland”.

ELLIOTT: At one show, a young man came to the dressing room asking for my autograph. I asked if he played guitar and he said he did. I wished him luck and asked his name. He said it was Bruce. Bruce Springsteen.

STONER: It was an evolving entity. It would change from night to night. It was always in flux, there were always surprises and it always kept you on your toes. That meant there was sheer terror on my behalf throughout the show as I knew there’d be something we’d never done and I had to hope the band could remember from rehearsal. And I had to hope Bob remembered it the same as the band did. We were all strung out, 30 feet across the stage, about eight of us, and everybody seemed to be on guitar.

SLOMAN: When Bob was on they’d all come out and watch. He was so great on that tour. A lot of these songs were epic journey songs and Bob was able to almost act them out. He was wearing whiteface. “Isis” is a great example, or “One More Cup Of Coffee”. These songs were very cinematic and you could really see him emoting.

McGUINN: Bob was amazing, full of surprises. You didn’t know what he was doing next.

BAEZ: He was spectacular. It was a stellar performance every night. I went down into the crowd. Sometimes people noticed me, but I’d just look at them and say “Sssh” and they’d not bother me.

STONER: There were all these stop-and-start type

songs that Bob was very enamoured of at that time, like “Durango” and “Oh, Sister”. Every time they started up again my heart would be in my throat wondering if these motherfuckers would know when to go. The whole time, I’m singing harmony, conducting with the neck of my bass and watching Bob’s mouth to see when the next syllable was coming. It was a high-wire act.

“It was a big party for a long time”

Baez as Bob. Sam Shepard’s film. Muhammad Ali attends the show at Madison Square Garden. The first leg concludes

McGUINN: T-Bone Burnett would lasso me when I was playing “Chestnut Mare”. Joan Baez and I would sing “Eight Miles High” and she’d do this dance in the middle of it, a sort of boogaloo that nobody would have thought of Joan Baez.

ELLIOTT: Joan warned me in Toronto she was going to do something during my set. She came out dressed in this very funny outfit, like a bobbysoxer with striped socks and a miniskirt chewing bubble gum doing a jitterbug. Nobody knew who she was, so one of our security guards lifted her over his shoulder and took her off the stage.

BAEZ: I remember dressing up as Bob for one show. You could not tell from a distance which of us was which. He didn’t have an ass, but we didn’t turn round for the public. I did a spectacular Dylan impersonation.

ERIC ANDERSEN: I was doing a show in Niagara Falls with Tony Brown, who played on Blood On The Tracks. We went to see Rolling Thunder, then went on for the finale. Bob asked if I wanted to do a number, but I was singing choruses, having

a good time. After the gig I went to the party and saw Joni and Ginsberg. I think there were a lot of drugs. Something had to keep it rolling.

McGUINN: It was a big party for

a long time.

SLOMAN: As well as playing

every night, Dylan was doing Renaldo & Clara.

ELLIOTT: The film is totally unrelated to anything that really happened. They are all last-minute made-up scenes that Bob made up. He invited Sam Shepard and his job officially was scriptwriter for this film, but we rarely had a written script.

BAEZ: The film was goofy. I had no particular confidence what would come out of the film.

I didn’t think there were any professionals around. It was like a Boy Scout camp making a cool film, that’s what it felt like and kind of what it ended up.

SLOMAN: “Hurricane” [Dylan’s November 1975 song about imprisoned boxer Rubin Carter] was a real return to his roots. He’d done a lot of songs about racial injustice and this wasn’t new for him to pick up the cause of a black guy screwed by the justice system. The last big event on the first leg was the Night Of The Hurricane at Madison Square Garden. Muhammad Ali was there, it was amazing.

ELLIOTT: We also did a concert at Carter’s prison for the inmates. They were all black. They didn’t appreciate Joni, she was too white. They didn’t tap their feet for Joni.

BAEZ: I’m pretty good at penitentiaries. I kind of get what the inmates want, what they’re missing, and how to relate. They’re usually Latinos or black, and I have that repertoire. I remember Joni singing something wordy, long and white, and they weren’t interested, they got restless. Bob didn’t have to think about it, he’s in his own stratosphere. They wouldn’t care if he got up and farted.

RIVERA: The prison was a very sad experience. At the Garden, I got to shake Ali’s hand. That was an incredible show. But almost every show was a great show, I don’t think we did a bad one. Every night and every place. We didn’t get tired. This was music that everybody was passionate about and an experience that we all knew was never going to happen again.

“It just faded away…”

The tour ends up where it began – in New York’s Greenwich Village, where one final revelation from Dylan awaits

RIVERA: Before the second leg, we did another benefit for Carter at the Houston Astrodome. It was an all-star concert with Stevie Wonder and our guest drummer was Ringo Starr. We all deferred our salaries for the fund.

McGUINN: I think somebody decided he’d lost

a lot of money, so they did another tour in ’76 at larger venues in the South. That wasn’t as much fun, the first half was great. I do remember we went to see Bobby Charles in Louisiana, and for dinner he had this alligator wrapped in aluminium foil on the table and a keg of beer. You poured yourself a beer and grabbed a hunk of alligator flesh. It tasted like chicken.

SLOMAN: The second part didn’t have the same spirit. You look at the footage and it’s a whole different Bob. He’s got a different outfit, he’s reinvented himself again. He was ready to move on, ’cos one thing he never does is repeat himself.

BAEZ: All the colour is gone, the pretty scarves and flowers, and with it the excitement. It wasn’t over, it just wasn’t the same.

KEMP: The second tour was similar but in a different location, so had a different flavour. It was a one-of-a-kind tour and that’s why it is legendary. No-one had done anything like it before or since.

McGUINN: It just faded away. There was never

a wrap party. The real party was at the front hanging out at Gerde’s before we left.

SLOMAN: Every night I got to see Dylan pour

his heart out in the most amazing fashion. At the end of the tour we were back at the Other End where it all began and somebody played “Like

A Rolling Stone” on the jukebox. I started kidding Bob, “You didn’t even play your best songs on

this tour!” And he said to me, “Ratso, did I ever

let you down?”