Ultimate Record Collection – The 1970s Part 1

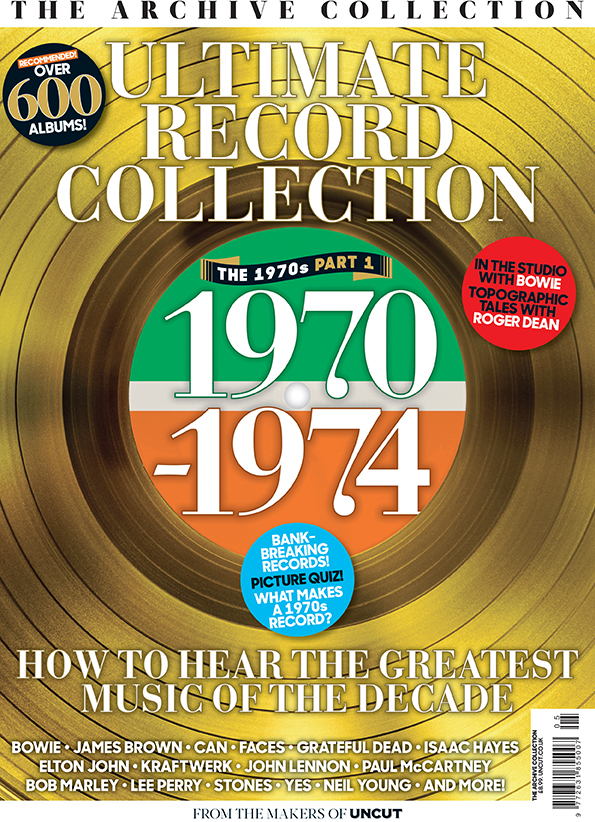

Brian Wilson postpones June tour due to mental health issues

Brian Wilson has postponed his June US tour due to mental health issues. In a candid letter published on his website, Wilson explains how his latest round of surgery on his back left him feeling “mentally insecure”.

“We’re not sure what is causing it but I do know that it’s not good for me to be on the road right now,” he writes. “I’m going to rest, recover and work with my doctors on this.”

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

Wilson was due to perform alongside fellow Beach Boy Al Jardine in a series of shows billed as Pet Sounds: The Final Performances. Wilson’s letter suggests the performances will be rescheduled, and his tour commitments for August and September currently remain unaffected.

“It is no secret that I have been living with mental illness for many decades,” writes Wilson. “There were times when it was unbearable but with doctors and medications I have been able to live a wonderful, healthy and productive life with support from my family, friends and fans who have helped me through this journey.

“As you may know in the last year or so I’ve had 3 surgeries on my back. The surgeries were successful and I’m physically stronger than I’ve been in a long time. However, after my last surgery I started feeling strange and it’s been pretty scary for awhile. I was not feeling like myself. Mentally insecure is how I’d describe it. We’re not sure what is causing it but I do know that it’s not good for me to be on the road right now so I’m heading back to Los Angeles.

“I had every intention to do these shows and was excited to get back to performing. I’ve been in the studio recording and rehearsing with my band and have been feeling better. But then it crept back and I’ve been struggling with stuff in my head and saying things I don’t mean and I don’t know why. It’s something I’ve never dealt with before and we can’t quite figure it out just yet. I’m going to rest, recover and work with my doctors on this. I’m looking forward to my recovery and seeing everyone later in the year. The music and my fans keep me going and I know this will be something I can AGAIN overcome.”

For help and advice on mental health issues, contact the Samaritans or Mind, the mental health charity.

Dr John dies aged 77

Mac Rebennack, aka Dr John, has died aged 77.

In a statement, Rebennack’s family said Dr John died on June 6, “toward the break of day”, following a heart attack.

— Dr. John (@akadrjohn) June 6, 2019

Born in 1941, Rebennack began playing in local New Orleans bands during the 1950s, later going on to work an A&R job at Ace Records.

As a teenager, he discovered drugs and later became a heroin addict. In 1960, the ring finger of Rebennack’s left hand was blown off in a shooting incident in Jacksonville, Florida and he switched to piano.

Despite his addiction issues, Rebennack moved to Los Angeles in 1964, becoming a respected session player, appearing on records by Aretha Franklin, Cher, Canned Heat, Irma Thomas, Professor Longhair and Frank Zappa among many others.

His 1968 debut album, Gris-Gris, establishing his visionary creative blueprint: a wild mix of R&B, funk and psychedelia generously sprinkled with New Orleans voodoo. The album also introduced Rebennack’s enduring musical personality, Dr. John Creaux the Night Tripper.

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

He signed with Atlantic, and in 1972 released Gumbo, featuring his versions of “Iko Iko”, “Let the Good Times Roll” and other New Orleans classics. The following year, he hit his commercial peak, when “Right Place Wrong Time” became a Top 10 in America.

Despite appearing in The Last Waltz, Rebennack’s fortunes declined during the Eighties. At the end of the decade, though, Ringo Starr invited Rebennack to join his inaugural All Starr Band Tour.

God bless Dr. John peace and love to all his family I love the doctor peace and love ?✌️?❤️??☯️☮️ pic.twitter.com/ljFWmMp9V9

— #RingoStarr (@ringostarrmusic) June 6, 2019

Rebennack continued to make music, including Anutha Zone in 1988 and the Dan Auerbach produced Locked Down in 2014. A serial collaborator throughout his career, he guested on albums as diverse as The Rolling Stones’ Exile On Main Street and Spiritualized’s Ladies And Gentlemen We Are Floating in Space and appeared in David Simon’s HBO series, Treme.

Click here to read our Album By Album interview with Dr John

Pixies announce new album, Beneath The Eyrie

Pixies have announced that their new album, Beneath The Eyrie, will be released by BMG/Infectious on September 13.

Listen to the lead single, “On Graveyard Hill”, below:

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

Beneath The Eyrie was produced by Tom Dalgety and recorded last December at Dreamland Recordings near Woodstock, NY. The making of the album was documented in a new podcast, helmed by author Tony Fletcher. “It’s A Pixies Podcast” launches on Apple, Spotify and all the usual podcast platforms on June 27.

Pixies will tour Europe throughout September and October, peruse the full list of dates below:

SEPTEMBER

13 Motorpoint Arena, Cardiff, UK

14 Pavilions, Plymouth, UK

16 O2 Academy, Birmingham, UK

17 O2 Academy, Leeds, UK

18 O2 Apollo, Manchester, UK

20 Alexandra Palace, London, UK

21 O2 Academy, Newcastle, UK

22 O2 Academy, Glasgow, UK

23 Usher Hall, Edinburgh, UK

25 Ulster Hall, Belfast, UK

26 Olympia Theatre, Dublin, Ireland

29 Sentrum Scene, Oslo, Norway

30 Cirkus, Stockholm, Sweden

OCTOBER

1 KB Hallen, Copenhagen, Denmark

3 TivoliVredenburg, Utrecht, The Netherlands

4 O13 Poppodium, Tilburg, The Netherlands

5 Columbiahalle, Berlin, Germany

7 Palladium, Cologne, Germany

8 Lucerna Music Hall, Prague, Czech Republic

9 Gasometer, Vienna, Austria

11 Estragon, Bologna, Italy

12 Todays at OGR, Turin, Italy

13 X-Tra, Zurich, Switzerland

15 Tonhalle, Munich, Germany

16 Forest National, Brussels, Belgium

17 Luxexpo, Luxembourg City, Luxembourg

19 L’Olympia, Paris, France

20 Le Radiant, Lyon, France

21 Le Liberte, Rennes, France

23 Sant Jordi Club, Barcelona, Spain

24 Riviera, Madrid, Spain

25 Campo Pequeno, Lisbon, Portugal

26 Coliseum, Galicia, Spain

The 18th Uncut New Music Playlist Of 2019

Busy weeks – so a little bit of catch-up here. The new Bon tracks are so good I’ve taken the liberty of including them both. Elsewhere, new/old jams from Howlin Rain and Bill Ryder-Jones, more good new music from Sufjan, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Sleater-Kinney and King Gizzard. Dive in.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner

1.

BON IVER

“Hey, Ma”

(Jagjaguwar)

2.

DJINN

“Djinn And Djuice”

(Rocket)

3.

HOWLIN RAIN

“Goodbye Ruby” [Live]

(Silver Current)

4.

SLEATER-KINNEY

“Hurry On Home”

(Mom + Pop)

5.

PIXIES

“On Graveyard Hill”

(PIAS)

6.

BILL RYDER-JONES

“Don’t Be Scared, I Love You (Yawny Yawn)”

(Domino)

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

7.

SUFJAN STEVENS

“Love Yourself”

(Asthmatic Kitty)

8.

RYUICHI SAKAMOTO

“This Is My Last Day 2”

(Milan)

9.

KING GIZZARD & THE LIZARD WIZARD

“Self-Immolate”

(Flightless)

10.

JAI PAUL

“Do You Love Her Now”

(XL)

11.

HACKNEY COLLIERY BAND

“Derashe”

(Veki)

12.

BON IVER

“U (Man Like)”

(Jagjaguwar)

Watch a trailer for Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story

Rolling Thunder Revue: A Bob Dylan Story, Martin Scorsese’s documentary about Dylan’s fabled 1975/6 all-star tour, launches on Netflix and in select cinemas on June 12.

You can now watch the official trailer below:

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

The accompanying box set, Rolling Thunder Revue: The 1975 Live Recordings, is released on June 7. You can read a review of that in the current issue of Uncut, in shops now or available to buy online by clicking here.

Hear Jesse Malin’s new song “Room 13”, featuring Lucinda Williams

Jesse Malin has announced that his new album Sunset Kids will be released on August 30.

It’s produced by Lucinda Williams, who also co-writes and features on the lead-off track “Room 13”. Hear that below:

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

Malin describes “Room 13” as “the heart of the record, about those meditative moments far out of your comfort zone, where you’re forced to reflect on the things that really matter.”

The title of Sunset Kids is a dedication to the people Malin lost during the making of this album, including its very own engineer David Bianco, his lifelong friend and bandmate Todd Youth and his father. Other guests on the album include Joseph Arthur and Green Day’s Billie Joe Armstrong.

Jesse Malin tours the UK & Ireland in June, check out the dates below:

June 15 Brighton UK The Haunt

June 16 Manchester, UK Deaf Institute

June 18 Norwich, UK Norwich Arts Centre

June 19 Oxford, UK The Bullingdon

June 20 Glasgow, UK King Tut’s Wah Wah Hut

June 21 Dublin, IR Whelans

June 22 Belfast, UK The Limelight 2

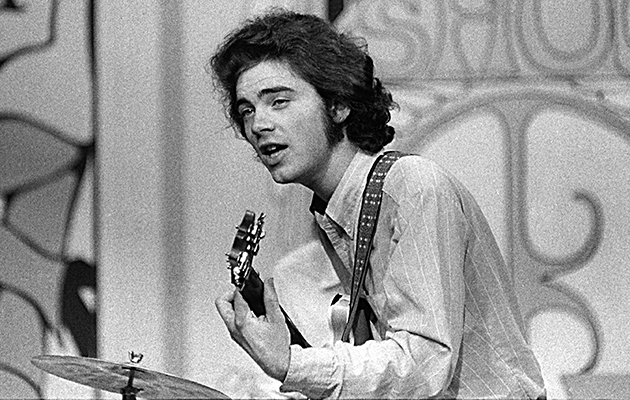

The 13th Floor Elevators: “We’re raising hell now!”

[From the July 2015 issue of Uncut]

Southeast of the Texas State Capitol Building is a small four-block street called Jinx Ave. Pulling up to a Wedgewood blue frame house, tucked beneath leafy pecan, ash and mesquite trees, down a path of paving stones, you can’t avoid thinking that it’s far too apt an address for the 13th Floor Elevators – a band whose genius was thwarted by a string of near-constant bad luck until they dissolved into acid-rock legend. When they fell, they fell from a high altitude, one that seemed impossible to return to.

Yet here in Clockright Studios, as unlikely as it seems, the Elevators – under the auspices of their leader, Roky Erickson – are preparing for a 50th anniversary reunion show at this year’s Austin PsychFest. A long white outer building opens up to reveal a small economical space, panelled in good wood, with oriental rugs, smartly framed posters, and an inner sanctum that holds vintage analogue equipment as well as more recent state-of-the-art gear. The studio is owned by Jason Richards, a member of Erickson’s recent backup band the Hounds Of The Baskerville. It got its name after the power blew out in the studio for a few days: when it came back on, the analogue clock read exactly the right time.

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

Things like that are common occurrences in the Ericksonian universe. Yet everything seems remarkably normal on this warm spring day. Two of the original band members — Erickson and drummer John Ike Walton – sit under a canvas umbrella sipping sweet tea, shielded from the late afternoon Texas sun. They are accompanied by bassist Ronnie Leatherman, who joined the band in June 1966, straight after graduating from high school.

Together, they wait to begin rehearsal. But one of their number is conspicuously absent. Electric jug player Tommy Hall is still in San Francisco, although he’s assured his fellow bandmates he will be in Texas for the show. He later tells me he has sworn off any inebriants before a show – he only smokes medical marijuana these days since his LSD connection dried up back in 2009. And, pressingly, he has to get a new electric jug. It’s been almost five decades since the founding members shared a stage together; or kept in touch with more than the occasional Christmas card. While Walton and Leatherman live within shouting distance from each other near their hometown of Kerrville, Texas, but they haven’t seen Erickson or Hall in more than 45 years.

Dressed in a black T-shirt, with mirrored sunglasses, jeans and black-and-white Vans embellished with racing stripes, Erickson closes his eyes and leans back in a white wrought-iron lawn chair. His scrupulously clean hands and preternaturally white fingers are stretched across the girth of his stomach like a belt. Breathing deeply, but not asleep, he seems to be conserving power. At this stage of life, it appears he’s figured out what is important to him. And taking things easy is one of them.

“Are you ready to go in there and practice?” his son Jegar asks him, inclining his head toward the studio about 15 feet from where his father is sitting. Erickson opens his milky blue eyes and fixes his son with a look, but doesn’t answer. Instead he turns his head to look at his wife. “Are we having steak for dinner?” he asks Dana, whom he first married in 1974, then again in 2008. “If that’s what you want, honey,” she answers, fussing a little with a strand of hair that has escaped her long black braid. Jegar asks his father again. This time he answers: “We might as well get it over with.”

The 13th Floor Elevators are perhaps rock’s most improbable comeback story. Never mind that it was five decades in coming. But Roky Erickson had a further distance to travel back than most. The prodigious amounts of LSD the band used to imbibe before shows had a profound effect on the frontman. When the Elevators performed at San Antonio’s HemisFair in 1968, Erickson began speaking gibberish on stage. The latest in a long string of similar, equally bizarre incidents, it resulted in the singer being taken to a Houston psychiatric hospital, where he was subjected to electroshock therapy. The band dissolved shortly after. Then, in 1978, guitarist Stacy Sutherland was shot by his estranged wife, Bunni, in a domestic dispute in Houston.

In their heyday, 13th Floor Elevators were bona fide rock stars: a little too good-looking for their own good, a little too dangerous-sounding, their hair a little too long, their pants pegged a little too much, their guitarist a little too brooding. Their debut single “You’re Gonna Miss Me” was a dissolute kiss-off to a love gone bad, with lyrics as beseeching as they were menacing. The song climbed halfway up the charts, landing the Elevators on Dick Clark’s American Bandstand twice in 1966. The song still looms large in Elevators’ lore.

“It is a really great pop song,” explains Patti Smith Band guitarist Lenny Kaye, who included it on his 1972 compilation, Nuggets: Original Artyfacts From The First Psychedelic Era, 1965–1968. “That song was the centerpiece of Nuggets. It’s got great hooky chords to start and it’s got that weird middle break with that kind of echo sound from Tommy Hall’s electric jug. I don’t think it has ever been used before or since. And those screams. They may be the best white screams. They’re on a par with Screaming Jay Hawkins.”

Kaye is not the only connoisseur to venerate either “You’re Going To Miss Me” or the Elevators themselves. ZZ Top’s Billy Gibbons – whose Houston psych group Moving Sidewalks were contemporaries of the Elevators – confirms the band’s pioneering sensibilities. “Roky and the 13th Floor Elevators were creating something otherworldly,” he explains. “Sound in a scene that had no previous incarnation. Psychedelia!”

The Elevators were brought together by Tommy Hall, a proto-hippie shaman, acid visionary and Texas musician. His plan was to hook up Erickson, then lead singer with The Spades, with another Texas band, the Lingsmen – whose line-up included guitarist Sutherland, drummer Walton, and bassist Benny Thurman. In Erickson, Hall found a voice for his acid revelations. While for his part, Erickson – a former child actor – had already written two songs by the time he was 15: “You’re Gonna Miss Me” and “We Sell Soul”. Founding bassist Benny Thurman explains the origins of the Elevators’ name in suitably Spinal Tappish terms: “Everyone else had only gone to 12. The music was so new that we called it the 13th floor.”

In the sleevenotes accompanying their 1966 debut, The Psychedelic Sounds Of The 13th Floor Elevators, the band advocated the use of LSD as a gateway to a higher state of consciousness. According to Billy Gibbons, they were “creating the vision of being able to go to an undiscovered space. Texas got bigger!”

“No rock band before or since ever delved as deeply into the idea of human consciousness being something that could be expanded into the higher evolution of the species,” says longtime supporter Bill Bentley, who co-ordinated the 1990 Erickson tribute album, Where The Pyramid Meets The Eye. “Tommy Hall worked in the world of psychedelics as a tool to help the progress of humanity. His song lyrics reflected what he learned while under the influence of LSD in a way that turned the band’s best songs, like ‘Slip Inside This House’ and ‘Postures (Leave Your Body Behind)’ into sonic sacraments for their acolytes.”

Almost from the first, Hall insisted that the band members ingest LSD before every show and “play the acid.” At first none of the members balked, embracing the spiritual, mind-expanding properties of the drug, but later there were dark rumblings that if they refused, Hall would sneak the substance into their drinks prior to shows. “The only way I could deal with it was pretend to take it and only take a quarter or half a tab at most instead of the whole,” explains bassist Ronnie Leatherman. Still slender as a boy, with graying hair, a baseball cap and a purple shirt, he has spent the past four decades working for a jewelry company. A perfect amethyst in his left ear will attest to the fact that he knows his gems. “If it was good, I might take some more later, but I really didn’t very often. Tommy was just real insistent, and I was young and wanting to experiment, of course. But we weren’t taking LSD to get blasted. It was spiritual. Stacy was very spiritual. He was a firm believer in God. I don’t have anything against Tommy. He could take all he wanted to. I just didn’t want to. But I don’t regret it a bit. And John Ike took it, but he just didn’t like it. And now he definitely doesn’t, and I wouldn’t ever again, that’s for sure.”

At 72, in his oversized white cowboy hat, Dockers, and striped shirt, John Ike Walton looks more like the manager of a neighborhood hardware store than a rock musician. When pressed, he admits he is reluctant to discuss the Elevators, preferring to save his memories for a book. “I’m tired of giving everything away. But for the record, I want to say, I did not take the LSD,” he huffs, contradicting much of what he has said in interviews over the years. Surprisingly, Erickson is more sanguine about his experiences with LSD. “I never really had a bad acid trip,” he confirms rather matter-of-factly. Admitting to more than 300 psychic excursions, he says, “You have to watch out for the way you view things and think it right. If you respected it, you would have a good trip; if you didn’t, you’d have a bad one.”

Unfortunately, the Elevators‘ existence proved to be a bad trip for the Texas establishment. The band were busted in a televised raid; although most of the charges were subsequently dropped, Hall and Sutherland struggled to find gigs in Texas under the terms of their parole. In 1969, meanwhile, Erickson was busted by the Austin police. In an attempt to avoid a prison sentence, he pled insanity and was sentenced to the Rusk State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in Austin. There, he was subjected to Thorazine treatments and electroshock therapy. He wrote a book of poetry and befriended a fellow convict, Jimmy Wolcott, an Elevators fan who had murdered his family while high on glue. Critically, Erickson also continued to write songs, forming a band called The Missing Links with his fellow inmates. “I would write these songs on my guitar,” he explains today, as he continues to recline in his lawn chair. “I was writing songs constantly there. I had them stored away in a box.”

++++++

There have been previous attempts to reunite the 13th Floor Elevators stretching back to 1972, when Erickson was finally discharged from Rusk. Did he miss the band?

“Yeah, sometimes I did.”

Did he ever think about putting it back together again?

“Yeah, I thought about it,” he allows. “They wanted us to do a get together of the Elevators when I came back. To regroup the band. It didn’t really work out.”

It’s not clear whether Erickson is entirely concerned with his band’s its 50th anniversary. Does he think their music still holds up today?

“They haven’t played in a long time, but the albums are still out there,” he says a little peevishly, with an odd choice of pronoun, which may prove revealing. “When I was in Philadelphia [actually Pittsburgh, living with his younger brother Sumner after leaving Rusk] I’d listen to the Elevators a little and they’re very exciting. I enjoyed listening to the words. They were talking about metaphysical stuff and things like leaving your body. But I think that’s a hard thing to do.”

So does it feel different being a member of the 13th Floor Elevators in 2015 than it did in 1965?

“Oh, I feel like I have it more down. See, you study, you know certain things,” he says mysteriously. “Things you didn’t know before. I’m studying trying to mingle fiction with existentialism, psychology. That sort of thing. You keep going and you get to where you can identify with what people are trying to teach you.”

Still, there are uncertainties and changes. Tommy Hall is no longer calling the shots from his hotel in San Francisco’s Tenderloin, where he lives on government assistance (and the “thousand a year or so” he claims to earn from Elevators royalties) and watches German television programs all day. More important, there are no drugs any more, save blood-pressure medicine for these 60-somethings. The band have also needed to find a suitable replacement for Sutherland, whose reverb-drenched guitar work was as critical to the band’s sound as Erickson’s unnerving scream and Hall’s electric-jug sorcery. In fact, it’s taking two guitarists: Fred Mitchim and Eli Southard. Southard, who had been playing in the Hounds Of The Baskerville since 2012, observes that Sutherland’s role in the band was crucial, and that the other guys “looked to him for all the cues.

“I really love the records,” he adds. “I wanted to sound as close to the record as I can get but still throw down a genuine-like vibrant performance. I can’t learn all those solos verbatim, mainly because he was just vamping out a lot of it anyway, and it’d kinda go against the spirit of it to just learn what he played that one time verbatim.”

While Southard is talking, Erickson gets up and walks into the air-conditioned studio. The band members — new and old — join him inside, taking their places around their instruments. Erickson settles himself in a chair in the centre of the room, while Walton squeezes in behind his drum kit which is pushed into the far corner. There is an awkward silence while they attempt to get the mics working properly. Jegar Erickson swoops in and swiftly resolves the problem. He removes a roll of black tape out of his pocket, pulls off a piece and puts it over a stray wire in front of his father and then steps back. Without hesitation the band start playing as one – as if they’d been doing this every day for the last 50 years, in fact – “Splash 1”, from their debut album. The song is one of their rare ballads. Southward begins proceedings picking out the song’s minimalist guitar lines before the rest of the band join in. Then Erickson starts singing; he co-wrote the song with Hall’s former wife Clementine, about what happened when the two of them met: “The neon from your eyes is splashing into mine / It’s so familiar in a way I can’t define. If anything, Erickson’s voice is more refined than it was those five decades ago, sounding a bit like the Airplane’s Marty Balin with a bit more tremor, a little more ache. His timing is impeccable, his pitch superb; the rest of the band are impressively tight.

They move quickly on to “(I’ve Got) Levitation,” an out-and-out rocker written by Hall and Sutherland. This version, which barely stretches beyond the two minute mark, is dirty garage rock at its best, as Erickson narrows his odd-shaped eyes and punctuates the song’s breaks with an appropriate “All right” that bring to mind a young Jagger. As soon as it starts, it stops. The silence in the studio is suddenly broken by the piercing scream that kicks off “You’re Gonna Miss Me”. What’s truly odd is that Erickson’s face doesn’t change expression at all when he emits the scream, almost as if it doesn’t come from him. In this version, Erickson comes in behind the beat; it seems slower, more sure-footed, yet more of a lament than the original version. After it closes, Walton takes off his big Texan 10-gallon hat and wipes his brow before they start in on “Roller Coaster”. Based on Hall’s recitation of the acid experience, the song on record is compressed and anxious but today it picks up steam as they play it. There is a palpable sense of tension dissipating when it finishes.

++++++

When Roky Erickson left Rusk Hospital in 1972, it was claimed he had forgotten all the words to the Elevators songs – but he could remember every single Dylan lyric. Six years ago, Erickson admitted to Uncut that was true. Evidently, things have changed in the intervening years. Jegar has assiduously printed off lyric sheets for the songs the band practice during rehearsal, and Erickson hasn’t needed to consult a single one, instead reeling off the words as if he’d written them only yesterday. In a break during the rehearsals, Southard explains that for quite some time, Erickson would regularly perform only two Elevators songs – “Splash 1” and “You’re Gonna Miss Me” during Hounds Of The Baskerville shows. But Southard noticed a change of attitude over the last couple of years.

“We started incorporating a lot of the Elevators tunes into the set, because Roky was really into it,” he reveals “We didn’t really expect that. I don’t know because I wasn’t around, but as I understand it he wasn’t really into playing those tunes with previous bands, for whatever reason. So when we just kind of pitched the idea, ‘Rok, would you want to try playing “Levitation” sometime, or “Fire Engine”? He was, “Well, yeah, I love those songs.’”

Back in Clockright Studios, Walton whoops, “We’re raising hell now!” Erickson nods in agreement. “Yup. It sounds good,” he adds. “Let’s do ‘Reverb’ next.” The song – actually titled “Reverberation” – was a co-write between Hall, Erickson and Sutherland. Thankfully, the lyric “You start to fight against the night that screams inside your mind/When something black, it answers back and grabs you from behind” no longer has the sway over them it once did. “Take it easy with that one,” reminds Erickson, then he says, “Was that four or five?” It transpires that this is code: asking about the time usually signifies that Erickson has had enough. “Want to take a break, Roky?” asks Jegar, who never calls his father “Dad”.

“Nope,” comes the reply. “We can do one more.”

After a little adjustment to his chair, Erickson is ready to go again, tapping his foot even though no music is currently being played. The band ease into “Tried To Hide”, a song Sutherland wrote about burying joints in the sandy beach. Erickson emits soft, approving “Yeahs” during the song. Three minutes later they’re done, which seems to thrill Erickson. “It was good today,” he enthuses. “Nice and easy. That big old cup of hot tea helped.” Although I didn’t see him have one. Yet for all his gnomic aspects, Erickson is clearly the band’s driving force. According to Jason Richards, the studio owner, “Roky is a workhorse. The more we put him to work and the more he sings every day, you’ll watch the rest of us get weary and tired, [but] Roky’s a machine. He just keeps going.”

Southard adds, “He’s got his own set of quirks. It’s not easy to learn them. He always likes to say, ‘Well, you guys are taking it easy on me.’ Which is his way of saying, ‘Please don’t make me play too many songs,’ or ‘Hey, I’m tired.’ I also think he wants it to be cool with everybody. Probably in the past he’s had a lot of contentious relationships with his bandmates. So he’s just like, ‘Let’s all just take it easy.’ He speaks his own kind of weird language, but he’s a lot sharper than I thought he was going to be. He’s really on point most of the time, and he can be the anchor on tour sometimes because he’ll be like, no, no, let’s all calm down. Or when things get tense he’ll make a joke.”

The key, according to Jegar, is not to be careful around him and “have straight conversations with him. He’s very deliberate in what he chooses to say and the messages he wants to put across. But he’s comfortable in his skin and he doesn’t have to overcompensate, so I just found [it’s best to be] really direct and always 100 percent honest, never misleading, because he knows if you’re not telling the full truth. He’s probably at a point where it’s like. ‘If you want to talk to me that way, I’ll respond back to you that way.’”

What’s the best way to communicate with Erickson Snr, then? Jegar considers his answer. “He doesn’t like pussyfoot conversations.” He says eventually. “He wants to be talked to like a dude. That’s what he likes about getting out with the band, now that he knows the band. It’s like, ‘Hey, Rok, how you doing?’ And game on. He likes getting out of the house and hanging out with his brothers and playing some music.”

And, of course, he likes steak.

Pavement are reforming again

Pavement have announced that they are reforming for the second time to play Primavera Sound festivals in Barcelona and Porto in 2020.

A Tweet from the band’s official account stated that these would be the band’s “only two worldwide shows in 2020”.

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

It’s official. We’re getting back together for two exclusive concerts in 2020. See you next June at Primavera Sound in Barcelona and NOS Primavera Sound in Porto! pic.twitter.com/FQeS1HODpI

— PAVEMENTtherockband (@pavement_band) June 1, 2019

Pavement previously reformed for a global tour in 2010 to coincide with the release of their best-of compilation Quarantine The Past.

Hear two new Bon Iver songs, “Hey, Ma” and “U (Man Like)”

Following last night’s headline show at All Points East, Bon Iver have released two new songs.

Hear “Hey, Ma” and “U (Man Like)” below:

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

Both tracks are credited to several writers alongside Bon Iver mainman Justin Vernon, including regular collaborators Brad Cook and BJ Burton. “U (Man Like)” features contributions from, among others, Bruce Hornsby, Moses Sumney, Wye Oak’s Jenn Wasner and Brooklyn Youth Chorus with Bryce Dessner. Read more about the various musicians involved here.

Says Vernon, “This project began with a single person, but throughout the last 11 years, the identity of Bon Iver has bloomed and can only be defined by the faces in the ever growing family we are.”

Roky Erickson dies aged 71

Roky Erickson has died aged 71.

Variety reports that the 13th Floor Elevators’ bandleader died on Friday, May 31, in Austin.

Erickson’s death was confirmed by his brother Mikel to Bill Bentley, the Texan-born journalist and former publicist who produced the all-star 1990 Erickson tribute album, Where The Pyramid Meets The Eye.

Born Roger Kynard Erickson in Austin, Roky formed his first band, the Spades, after dropping out of high school in 1965. Later in the same year, he formed the 13th Floor Elevators along with electric jug player Tommy Hall and guitarist Stacy Sutherland.

Taken from their 1966 debut album The Psychedelic Sounds Of The 13th Floor Elevators, the band’s single “You’re Gonna Miss Me” became a regional hit.

“It is a really great pop song,” Lenny Kaye, who included the song on his legendary garage rock compilation, Nuggets, told Uncut. “That song was the centerpiece of Nuggets. It’s got great hooky chords to start and it’s got that weird middle break with that kind of echo sound from Tommy Hall’s electric jug. I don’t think it has ever been used before or since. And those screams. They may be the best white screams. They’re on a par with Screaming Jay Hawkins.”

The Elevators went on to release three more albums: Easter Everywhere (1967), Live (1968) and Bull Of The Woods (1969).

After the Elevators broke up, Erickson played in a series of other bands throughout the ’70s. After a fallow Eighties, Roky enjoyed renewed attention in 1990, with the release of Where The Pyramid Meets The Eye, which featured covers by R.E.M., Primal Scream, Julian Cope and The Jesus And Mary Chain.

In 1995, Roky released All That May Do My Rhyme, and he published Openers II, a collection of his lyrics. A 2005 documentary You’re Gonna Miss Me shone a spotlight on his personal struggles.

In his later years, he toured regularly, backed by such acts as the Black Angels, and collaborated with Mogwai on their 2008 track, “Devil Rides”.

In 2010, he released the album True Love Cast Out All Evil, which featured Okkervil River as his backing band.

Erickson finally reunited with the 13th Floor Elevators in 2015 and headlined Levitation, the Austin psych-rock festival that had been named after one of their songs.

Mavis Staples – We Get By

‘Change’ is not a theme one expects from an artist approaching her 80th birthday. More usual would be a reprise of old glories or some Johnny Cash-style meditations on death. Mavis Staples is not so easy to predict, however. 2016’s Living On A High Note deliberately requisitioned songs that had a joyous, upbeat feel. The three recent albums she made with Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy – an unexpected pairing for sure – ranged wide in both their choice of material, from Randy Newman to George Clinton by way of gospel standards, and in their musical treatment. 2017’s If All I Was Was Black, for example, often sounded like “Family Affair”-era Sly Stone.

On We Get By, Staples rings the changes again, this time working with Californian bluesman Ben Harper on a set that ranges from funky to subdued. It’s a sparser affair than the Tweedy-produced trio, adding only backing voices to a bass/drums/guitar lineup in which Harper’s searching playing provides the principal, sometimes sole counterpoint to Mavis’s earthy, heartfelt vocals, their power remarkably intact in her advancing years.

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

Staples and Harper have worked together before as one of the pairings on Living On A High Note. Born 30 years apart, they share a history of political activism. Mavis’s advocacy stretches back to the Civil Rights struggles of the 1960s, when her father, a close friend of Martin Luther King, lent the Staple Singers to the movement’s soundtrack. Her commitment has never wavered. Harper has been similarly relentless since he arrived in 1994 with Welcome To The Cruel World, an album whose standout, “Like A King”, paid tribute to both Martin Luther King and Rodney King as martyrs to the Civil Rights cause.

At first it seems that this will be an album of protest songs. “Change”, the opener and lead single, is funky blues with a John Lee Hooker groove and a snappy vocal that’s custom cut to become an anthem for today’s troubled times. “One’s the number, blue’s the colour, now’s the time/We gonna change around here,” snaps Mavis to a background of gospel voices, while Harper throws in a dirty solo. We may be hearing a lot of more of it in the next two years.

After that, however, the tone of the record begins to soften and take on a more soulful hue. The defiance of “Anytime” is set to a riff that could be from Stax-era Staples, adorned with some off-kilter guitar work. “We Get By” is slower still, a testimony to the stoicism of people who have little but survive on “love and faith” and sung like a lovelorn B-side on an old soul single.

That imaginary single might have “Sometime” on its A-side. Its lyric – “Everybody got to change sometime/Cry sometime/Pray sometime” – is a thread that has run through blues and gospel traditions for the last century, and gets an infectious treatment here, with Harper laying down a rolling, reverberating groove much in the manner of the late Pop Staples, while hand claps and gospel hollers help drive things along.

There are more personal pieces here. “Hard To Leave” is a love song addressed to a lifelong companion, comparing the passage of time to a warm summer breeze, and detailing the intimacy of “softly reaching for your touch in my sleep”. More stringent is “Chance On Me”, calling on a stone-hearted lover to open up and embrace possibility, delivered with an anguish that’s matched by Harper’s stinging solo. The same forlorn mood haunts “Never Needed Anyone”, an achingly intimate piece that verges on despair.

Mavis has always walked an ambiguous line between the sacred and the secular, her records often managing to inhabit both worlds simultaneously. So it is with “Stronger”, where the “Nothing is stronger than my love for you” chorus might equally be addressed to a lover or to Jesus; take your choice. There isn’t much ambiguity about “Heavy On My Mind” or “One More Change”. The former is almost a farewell – “We tried so hard to slow this world down/But now my love is in the ground.” Delivered spoken as much as sung and backed only by Harper’s spare guitar, it’s a deep, affecting piece. The “One More Change” of the album’s final track isn’t specified as death but it’s implied. Unsurprisingly, it’s a harrowing piece, with Mavis hoarse and tormented; but soaked in gospel influences as it is, it’s also transcendent, which is the gift that Mavis Staples has been bringing since she was a 1950s teenager singing “Uncloudy Day” with her family.

Mac DeMarco – Here Comes The Cowboy

Every artist contains a multitude of selves, a good many of which may not be on speaking terms with each other a lot of the time. Efforts must nevertheless be made to maintain some kind of coherent identity – after all, there may be no worse sin in the age of Instagram than having an inconsistent brand.

Yet there are some people who feel quite comfortable about being one of Kris Kristofferson’s walkin’ contradictions. As both a craftsman of growing sophistication and a dude who’s always ready to be his own punchline, Mac DeMarco could be modern music’s most bewildering and endearing example.

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

There are moments on the Canadian’s fourth album of such grace, simplicity and sweetness, they could only be created by a singer and songwriter of the utmost sensitivity and maturity, one who’s able to look deep down into the murkiest crevices of his heart and find the most direct means of expressing what he found. On Here Comes The Cowboy, the most affecting results of this continual process of excavation include “K”, an achingly sincere addition to DeMarco’s exquisite canon of ballads for his girlfriend, and “Skyless Moon”, one of several more darkly hued songs that suggest that when it comes to his taste in early-’70s troubadours, the 28-year-old may now have less of an affinity for James Taylor’s casual ease and more for Nick Drake’s stark desolation.

Such songs add further nuance and texture to the more melancholy sensibility that strongly emerged on 2017’s This Old Dog. DeMarco demonstrating a new power and depth in his writing, songs like “Dreams Of Yesterday” and “Moonlight On The River” saw him explore the confusing welter of emotions he felt upon seeing his estranged father on what appeared to be his deathbed. (The singer admitted to feeling even more confused when his dad’s health rebounded.)

If Here Comes The Cowboy contained nothing but these moments, it could’ve easily earned DeMarco the respect he’s due from the doubters who view him as a fun-loving, beer-swilling goofball who’ll do whatever it takes to keep an audience entertained (and do it minus his pants). Of course, that other Mac came to this party, too. He even brought his gong.

As heard in “Choo Choo” – an irresistibly daft, cod-funky mid-album exercise in comic relief that also gives DeMarco the opportunity to do a steam-whistle impersonation – the telltale reverberations of the golden king of percussion instruments are another indication that he’s not so eager to leave childish things behind. He’d rather have an outlet for his cheeky, occasionally juvenile sense of humour, which is also discernible in the new album’s abundance of cowboy kitsch. The opening track entails him repeating the album’s name in a corny drawl – elsewhere, he sings of “pretty cattle”, hopping trains and a sweetheart who’s unsure whether to stay down on the farm. While DeMarco’s abiding love of shtick may frustrate the admirers who recognise his capabilities, Here Comes The Cowboy is the strongest evidence yet that his many selves can coexist in a surprisingly harmonious manner.

Indeed, it shows a growing courage on his part to let those contradictions be so plain to the ear. That’s down to the spare, relatively unadorned style DeMarco chose for the mostly subdued songs he recorded in January in his Los Angeles home studio with the help of his touring sound engineer Joe Santarpia. (Drugdealer’s Shags Chamberlain and Alec Meen of DeMarco’s live band provided further assistance.) Whereas DeMarco lent a smeary, smudgy quality to the sounds on his 2014 breakthrough Salad Days by multi-tracking his vocals and using varispeed tape effects and other tactics, he’s largely content to leave well enough alone here. The layers upon layers of synthesisers that made This Old Dog standouts like “On The Level” so shimmering and sumptuous have also been reduced to more modest levels.

All that marks a dramatic shift for a musician whose early releases were steeped in a particular late-’00s strain of lo-fi maximalism, when DeMarco antecedents like Ariel Pink slathered everything they touched in reverb and anything else they could use to simulate the sound of a chewed-up cassette tape. Instead, on songs like lead-off single “Nobody”, DeMarco leaves ample space between the few elements he uses besides his forlorn vocals: a loping beat, a few plucked guitar notes, a burbling synth that struggles to stay in tune.

The new album’s bare-bones production aesthetic may not be hugely surprising to listeners familiar with last year’s Old Dog Demos and the other collections of early-draft recordings that DeMarco has released as stopgaps between his albums proper. But there’s nothing rough or tentative about the performances here. For one thing, his singing has never been more expressive. On “Preoccupied” and “Heart To Heart”, he shifts back and forth from a lazy murmur to a sultrier croon with a new-found finesse. The spare setting also gives new prominence to the emotional vulnerability that he’d previously preferred to obscure, as well as the thornier feelings that he used to only hint at or hide inside wisecracks.

Longings for home fill many of the songs, as befits the wandering-cowboy motif. Out on the range, our hero contends with a deepening darkness. On “Nobody”, he calls himself “another creature who’s lost its vision”. The good cheer in the ragtag-singalong “Baby Bye Bye” belies the bitter edge in the lyrics: “Another night you don’t sleep at all/You lay awake waiting for her call/But it never comes and it never will”. An equally fraught successor to This Old Dog’s poignant “Moonlight On The River”, “Skyless Moon” charts a loss of hope and time spent too carelessly. “No-one wants you singing along,” DeMarco sings before making a high lonesome sound of his own.

Since the mood sometimes threatens to grow too heavy, listeners may feel supremely grateful for digressions that might’ve seemed self-indulgent if they weren’t so crucial for the balance of elements and emotions here. In other words, Here Comes The Cowboy needs the big lovey-dovey burst of “K” just as much as it needs the nutty levity of “Choo Choo”. Another dose of loping, whacked-out funk, “The Cattleman’s Prayer” provides the silliest of codas. “Yee-haw!” cries DeMarco before unleashing a series of cackles and a closing, “Get along, li’l doggie!” It’s a fitting final flourish for an artist who’s unafraid to seem ridiculous if it gets him to where he wants to go. The result is an album that’s braver, weirder and richer than most of his more sensible and brand-conscious peers could ever manage.

Watch a video for Bruce Springsteen’s new song, “Tucson Train”

Bruce Springsteen has released a video for “Tucson Train”, the latest song to be taken from his new album Western Stars, due out June 14.

Watch it below:

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

The video was directed by Thom Zimny, who also helmed the Springsteen On Broadway Netflix special and The Ties That Bind documentary on the making of The River. The video features many of the musicians who appear on Western Stars.

Hear Sleater-Kinney’s new single, “Hurry On Home”

Sleater-Kinney have released a new single, their first new music since 2015’s No Cities To Love.

Hear “Hurry On Home”, produced by Annie Clark (AKA St Vincent) below:

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

No album has yet been announced but a press release teases “more eagerly anticipated new music on the horizon”.

Regarding this, the band’s Carrie Brownstein says, “Instead of just going into the studio to document what we’d done, we were going in to explore and to find the essence of something. To dig in deeper.” Corin Tucker says working on the new music “was like this manic energy of empowerment.”

Sleater-Kinney have also announced a North American tour for the autumn – for the full list of dates visit their official site.

Hear two new Sufjan Stevens songs

Sufjan Stevens has today released two new songs in celebration of Pride Month.

Hear “Love Yourself” and “With My Whole Heart” below:

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

“Love Yourself” is based on a sketch Stevens wrote 20 years ago – the original 4-track demo he recorded in 1996 has also been made available, as well as a short instrumental reprise. “With My Whole Heart” is a completely new song that Stevens wrote as a personal challenge to “write an upbeat and sincere love song without conflict, anxiety or self-deprecation.”

Both tracks are available on all digital platforms now, and will also be released on limited-edition 7” vinyl on June 28 via Asthmatic Kitty. A portion of the proceeds from this project will go to two organisations that provide support for LGBTQ and homeless kids in America: the Ali Forney Center in Harlem, NY, and the Ruth Ellis Center in Detroit, MI.

Cate Le Bon: “I hate everything I do right after I’ve done it!”

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

Originally published in Uncut’s June 2019 issue

“Quite different? Yeah, it’s almost the complete opposite,” says Cate Le Bon, pondering her move from Los Angeles to rainy Lake District. There, she took a year-long course at a renowned furniture school. “Since finishing school,” she explains, “I made a chair that looks like my record sounds. I’m gonna build that chair again during the Marfa Myths annual festival in April. I’ve been asked to do something musical at the festival, but it’s like, ‘No way, I’m here to build a chair…’”

The new album in question, Reward, is Le Bon’s fifth, and perhaps her most complete work. Taming the weirdness of Crab Day and her records with White Fence’s Tim Presley, it finds the Welsh singer-songwriter composing primarily on piano. Now back in her native Cardiff, Le Bon takes some time out on her birthday to talk us through her work so far, from 2009’s Me Oh My and Drinks all the way through to this year’s Reward and the latest Deerhunter album, which she produced. “I hate everything I do right after I’ve done it,” she laughs, “then sometimes I hear a song and go, ‘Oh yeah, that one’s all right!’ It depends what mood I’m in!”

____________________

CATE LE BON

ME OH MY

IRONY BORED, 2009

Le Bon’s enchanting debut, stripped-down and folky

Kris Jenkins, who played with Super Furry Animals a lot, had seen me open for Gruff Rhys and told me I should go and do some recording with him at his studio, Signal Box. He’s a wonderful man, really kind, really encouraging, so I started working on a record and had lots of fun, and experimented. I’d never really been into a studio before, and we had this loose idea to make a record, but I had this moment – I think it was where I was putting down the mouth harp – where I thought, ‘Oh my God, we’ve completely lost our way…’ And I totally scrapped that first record. So I got 10 songs together and rehearsed with a band and then took that into Signal Box again, but with a bit more structure. I couldn’t even tell you what that scrapped record sounded like – it sounded like about 15 different records playing at the same time! I guess Me Oh My was probably a reaction to having become completely lost, so it was pretty stripped-back and pretty classic, I suppose, instrumentation-wise. I think it was pretty indicative of what was going on musically then. There was a lot of talk of freak folk and psychedelia, and I guess it seemed like the record to make at that time.

____________________

CATE LE BON

CYRK

OVNI/TURNSTILE, 2012

A more freewheeling album, inspired by Le Bon’s new

German passions

What had happened in between the debut and this was I’d found krautrock. I discovered Faust IV, which continues to be my all-time favourite record – it’s one of the best records ever, I think. Its playfulness and experimentation, not just with instruments, but with melodies and form. It’s insanely inspiring. And I had probably learnt a bit more about being in a studio, that you can employ abandonment and still get a record finished. I was back at Signal Box for Cyrk, with Kris Jenkins – I was again experimenting, but with one eye on actually having to finish a record so it doesn’t turn into a quagmire. I remember Kris really pushing me to try loads of things and not be timid in the studio, so it was a really joyful, exciting process. The “Cyrk II” EP collected the slower songs from these sessions – I guess things sometimes pool together in two very separate puddles. Gruff Rhys worked out the tracklists for this album, and Me Oh My and Mug Museum, I think.

Morrissey – California Son

For a brief moment in 2006, Morrissey was dangerously close to being embraced by his homeland. “Irish Blood, English Heart” had entered the charts at number three. You Are The Quarry was his first solo album to go platinum. And then he outperformed Paul McCartney and David Bowie in the BBC’s poll of Britain’s Greatest Living Icons.

It all feels a lifetime ago. Since then it’s hard to imagine a more sustained project of artistic self-sabotage: World Peace Is None Of Your Business, released in July 2014, then withdrawn barely three weeks later following a bitter dispute with his label; Low In High School, launched in 2017 with interviews lauding Islamophobes and rehashing far-right talking points, followed by a cancelled European tour.

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

If he’d released a crowd-pleasing covers album in 2007, he might have finally ascended to the status of dotty, domesticated national treasure, alongside Alan Bennett, Elton and David Hockney. As it is, in this context, California Son can’t help but feel like a fairly desperate attempt to reboot the career before he terminally alienates his fanbase.

On the face of it, it’s a strange success. For those still keeping count, “Morning Starship” is his best single since “Something Is Squeezing My Skull”. Though it was glam rock that warped his adolescent brain, he’s not often been able to translate that freaky formative rapture into his own music – “Panic” and “Shoplifters” bought Bolan’s cosmic boogie down to provincial highstreets, while his live covers of Bowie and Roxy too evidently echoed the pale teenage boy singing along in his box bedroom. But here he transcends Jobriath’s original, with Joe Chiccarelli’s sumptuous, sci-fi baroque production framing an ardent, imperious vocal.

The straitlaced cover of “It’s Over”, the album’s first lead song, had hinted that he was going to play it safe in a Richard Hawley/torch song twang kind of way, aimed squarely at the heart of Radio 2, but “Morning Starship” suggested that California Son might be a more ambitious affair, a reckoning and refashioning of his own back pages that might add up to a more telling musical autobiography than his own Autobiography, and a pop art confection to place alongside Bryan Ferry’s These Foolish Things or Bowie’s Pin Ups. You might expect a collection of songs to rival his Meltdown curation in its heterogeneity: some girl groups, some glam, some MOR (he should record his cover of Gilbert O’Sullivan’s “I Didn’t Know What To Do” sometime), some bewildering transgender artsong.

But though it has plenty of light relief in loving renditions of turn-of-the-decade soft pop (the best of which is a giddy take on Laura Nyro’s “Wedding Bell Blues”, with backing vocals from Green Day’s Billie Joe Armstrong) California Son proves to be a more peculiar affair, a rum collection of American artfolk from the 1960s and ’70s. Once upon a time the young Morrissey crooned “I thought that if you had an acoustic guitar/Then it meant that you were/A protest singer/Oh I can smile about it now but at the time it was terrible”, and carefully positioned himself away from the mid-’80s Red Wedge agit-pop enragés he frequently shared stages with. But in many respects this is an artfully framed album of cosmic protest songs, not so much an apology for his increasingly eccentric geopolitical turn as a contextualising of it.

Here, after all, is a stentorian take on “Only a Pawn in their Game”, the song where Dylan explored the perspective of the “poor white on the caboose of the train” who is taught to “hide ’neath the hood”, and “kill with no pain”. The song is now so safely tamed and framed within sentimental pop-histories of the Civil Rights movement that it’s hard to hear just how scandalous it might once have been to express some degree of curiosity, if not sympathy with the thoughts of the white trash who ended up in the Klan. Hard as it might be, for example, to write a song from the perspective of the family of a boy joining the NF (as Morrissey did on “National Front Disco”). It’s an interesting comparison, one which casts Morrissey as a brave prophet of systemic injustice, much like the venerable Nobel laureate. But in a moment when an actual white supremacist is in the White House, judging that there are some “very fine people” in the Klan, it feels profoundly tactless at best. Moreover, Dylan has never, as far as we know, advocated voting for Britain First, which renders fine considerations of moral complexity somewhat moot.

He reprises his elegiac protest croon on a waltz through the mud and murder of Phil Ochs’ “Days of Decision”, but he’s on safer ground on his covers of female artists. Joni Mitchell is an underappreciated influence on the Morrissey canon – “Amelia” alone is at the core of at least three of his finest songs – but his version of “Don’t Interrupt The Sorrow” is a little too faithful, and his band unable to emulate Mitchell’s uncanny strum and swoon. “Suffer The Little Children” originally by Buffy Sainte-Marie, is stronger, beefed up with honky-tonk swagger, as it surveys the nation’s children, institutionalised into corporate slavery.

The album builds to a glorious swansong with Melanie Safka’s “Some Say I Got Devil”. Originally released on her 1971 album Gather Me, it sounded like a wistful, Greenwich Village version of some old East European Romany folksong, a la “Those Were Those The Days, My Friend”. Here Chiccarelli and the Morrissey band recast it as a relentless march to the scaffold, in the mode of Klaus Nomi – that is, a perfect Morrissey showstopper, tailor-made for the final curtain of his forthcoming Broadway residency. California Son may not entirely succeed in repositioning Morrissey as a righteous protest singer, boldly crooning truth to power, but in fleeting moments like this, it confirms him as as a peerless modern practitioner of deep song, the pop artist who can divine, even in the work of the singer of “Brand New Key”, Lorca’s dark, abymsal spirit of duende.

Rory Gallagher: “The energy level was frightening”

The new issue of Uncut – in shops now or available to buy online by clicking here – features an extensive profile of Irish blues guitarist Rory Gallagher, whose legend has only grown since his premature death in 1995.

In the piece, Graeme Thomson talks to Gallagher’s family, friends and bandmates to assemble a portrait of complex figure – a quiet, guarded personality who poured his heart and soul into his intense and febrile performances.

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

He also reveals how Gallagher almost joined The Rolling Stones. “[Mick] Jagger had been very positive about Rory in interviews and particularly liked that Rory had a good sense of country music,” recalls Donal Gallagher, Rory’s younger brother and longstanding manager. Gallagher jammed with the band for three days in Rotterdam, playing tracks from the forthcoming Black And Blue album. “On the final night he was asked up to Keith’s suite to have a chat about things,” says Donal. “Keith was comatose. Rory waited all night for him to wake up – but he never did.” With matters unresolved, Gallagher headed for the airport, already cutting it fine for his own Japanese tour.

In the end, Ronnie Wood got the Stones gig, and Gallagher continued ploughing his own unique furrow. Would the combination of a mercurial Irish bluesman and the world’s biggest rock’n’roll band have worked? “I don’t think so,” says Gerry McAvoy, who played bass with Gallagher from 1971–1992. “Rory was a frontman in his own right.”

“Nobody could work a stage like Rory,” said Ted McKenna, Gallagher’s former drummer. “Clapton certainly couldn’t do it, not even Hendrix could. The energy level was frightening, quite honestly. He would wear a crowd out.”

“He’s the equal of any guitarist you might care to mention, and perhaps he doesn’t get the coverage he deserves,” adds his nephew Daniel Gallagher, who oversaw Blues, an illuminating new anthology of largely unreleased Gallagher performances. “But he didn’t care about being voted No 1. He didn’t want to be a superstar; he didn’t want a cloak-and-dagger lifestyle.”

The quiet, handsome boy from Cork possessed a fierce belief in his own abilities and an unswerving idea of what was best for his music. “He was such a private individual, all I could do was witness the artist in him and the torture he put himself through,” says Donal Gallagher. “For good or ill, Rory ran his own race.”

You can read much more about Rory Gallagher in the new issue of Uncut, out now with The Black Keys on the cover.

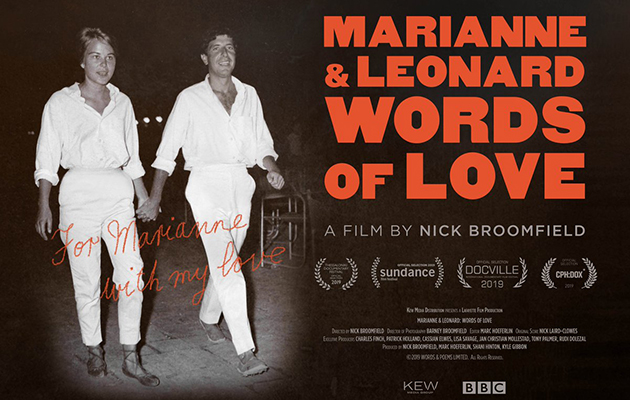

Watch a trailer for Marianne & Leonard: Words Of Love

As first featured in the March 2019 issue of Uncut, Nick Broomfield’s Leonard Cohen documentary will be released in UK cinemas on July 26.

Marianne & Leonard: Words Of Love is billed as a “beautiful yet tragic love story between Leonard Cohen and his Norwegian muse Marianne Ihlen… who was the inspiration for several of Cohen’s best-known songs including ‘Bird on a Wire’ and ‘So Long, Marianne’.”

Watch the first trailer below:

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home!

Speaking to Uncut earlier this year, Bård Kjøge Rønning – a Norwegian filmmaker who contributed to the documentary – said that, “Nick’s film is really based on his personal involvement with Marianne. They were seeing each other in London for almost half a year, in ’68. And he built this story on the character of the Marianne that he knew. Nick told me that Marianne had this special kind of energy she gave to everyone. And she gave it to him. He was 20 at the time, and doubting whether to be a filmmaker. She said, ‘Go for it.’ She inspired him a great deal.”