The Rolling Stones on our minds a lot this week, with the Keith Richards book finally out (please have a look at Allan’s immense review in the new Uncut), and a pile of page proofs from our forthcoming Rolling Stones Ultimate Music Guide for me to read.

The 41st Uncut Playlist Of 2010

Massive Attack to release music ‘spontaneously’ in 2011

Massive Attack have said they will “spontaneously” release new music during 2011.

Robert ‘3D’ Del Naja from the Bristol band admitted that “it’s more fun putting things out randomly” than sticking to a schedule.

“We got quite a bit of EPs out next year,” he told Spinner. “We’re tired of the cycle of album, tour. It’s more fun putting things out randomly, sort of spontaneously. We’ve done it quite traditionally this year, so maybe next year, a bit unorthodox.”

Meanwhile, Massive Attack[ will release their ‘Atlas Air EP’ on November 22. The four-track EP will include two new mixes of ‘Atlas Air’, plus a new song called ‘Redlight’, which features Elbow‘s Guy Garvey. Proceeds from the EP will be donated to War Child.

Latest music and film news on Uncut.co.uk.

Uncut have teamed up with Sonic Editions to curate a number of limited-edition framed iconic rock photographs, featuring the likes of Pink Floyd, Bob Dylan and The Clash. View the full collection here.

Peter Saville designs headstone memorial for Tony Wilson

Tony Wilson‘s memorial headstone has been unveiled, having been designed by his long-term Factory Records cohort Peter Saville and his associate Ben Kelly.

The black headstone, which is made of granite, is now sitting at The Southern Cemetery in Chorlton-Cum-Hardy, Manchester, reports Creative Review.

Wilson died of a heart attack in 2007, following a long-term battle with cancer. He is referred to on the headstone as a “broadcaster and cultural catalyst”. It also features the following book extract, selected by Wilson‘s family and taken from Isabella Varley Banks‘ 1876 novel The Manchester Man:

“Mutability is the epitaph of worlds/Change alone is changeless/People drop out of the history of a life as of a land/Though their work or their influence remains.”

Despite being designed by Saville and Kelly, the headstone does not feature one of Factory‘s trademark catalogue numbers. Wilson‘s coffin, labelled FAC 501, was the last of these.

Paul Barnes and Matt Robertson also helped Saville and Kelly to design the headstone.

Latest music and film news on Uncut.co.uk.

Uncut have teamed up with Sonic Editions to curate a number of limited-edition framed iconic rock photographs, featuring the likes of Pink Floyd, Bob Dylan and The Clash. View the full collection here.

Loretta Lynn recruits The White Stripes for tribute album

The White Stripes are among the bands to be handpicked by Loretta Lynn to feature on a tribute album featuring cover versions of her songs.

‘Coal Miner’s Daughter: A Tribute To Loretta Lynn’ is released on November 9 in the US, and also features covers by Paramore, Kid Rock, Faith Hill and Carrie Underwood.

The White Stripes have offered their 2002 version of ‘Rated X’ for the release. In 2004, Jack White produced, played on and co-wrote Lynn‘s album ‘Van Lear Rose’.

The tracklisitng for ‘Coal Miner’s Daughter: A Tribute To Loretta Lynn’ is:

Gretchen Wilson – ‘Don’t Come Home A Drinkin’ (With Lovin’ On Your Mind)’

Lee Ann Womack – ‘I’m A Honky Tonk Girl’

The White Stripes – ‘Rated X’

Carrie Underwood – ‘You’re Lookin’ At Country’

Alan Jackson and Martina McBride – ‘Louisiana Woman, Mississippi Man’

Paramore – ‘You Ain’t Woman Enough (To Take My Man)’

Faith Hill – ‘Love Is The Foundation’

Steve Earle and Allison Moorer – ‘After The Fire Is Gone’

Reba featuring The Time Jumpers – ‘If You’re Not Gone Too Long’

Kid Rock – ‘I Know How’

Lucinda Williams – ‘Somebody Somewhere (Don’t Know What He’s Missin’ Tonight)’

Featuring Loretta Lynn, Sheryl Crow and Miranda Lambert – ‘Coal Miner’s Daughter’

Latest music and film news on Uncut.co.uk.

Uncut have teamed up with Sonic Editions to curate a number of limited-edition framed iconic rock photographs, featuring the likes of Pink Floyd, Bob Dylan and The Clash. View the full collection here.

Jonny: “Jonny”

Spent a sizeable part of yesterday afternoon grappling again with “The Age Of Adz”, with little progress. It made me think, beyond the Sufjan Stevens album, there have been a good few albums this year, eagerly anticipated by me, that I’ve ended up delicately avoiding talking about here. Big personal disappointments, in other words: The Hold Steady’s “Heaven Is Whenever” and the Black Mountain album, whose title I’ve momentarily forgotten, spring to mind. I’d also, I think, end up filing “Shadows” by Teenage Fanclub in there: not a crushing disappointment, as such, more a mild, wearying one. It’d be churlish – and hopefully out of character – to criticise a band for growing older and reflecting changes of pace and perspective in their music. But struggling to articulate the frustration, I wish TFC had stuck at trying to be a rock band, rather than settling for being an indie one. That Raymond’s aesthetic hadn’t seemed to triumph over that of Norman and Gerry. Jonny, it must be said, are an indie band – or rather an indie project of sorts, featuring the Fanclub’s Norman Blake and Euros Childs, a tremendously gifted singer-songwriter who seems to have been bumbling along mostly below the radar since Gorky’s Zygotic Mynci split up. Their album, “Jonny”, is nothing like a return to the crunch of “Bandwagonesque”; if anything, it’s Childs’ musical history that’s referenced much more closely. It does, though, have a sprightliness, an ease and playfulness about it which comes as a relief after “Shadows”. Childs mostly takes the lead, but while Blake-fronted songs like the folk-rockish “You Was Me” and, especially, the lovely “Circling The Sun” would have fitted onto “Shadows” neatly enough, they seem to have a propulsion and lightness of touch which is, to me at least, much more pleasurable. “Candyfloss”, meanwhile, is an inspired coupling of the two talents – a Gorkys-style verse and a TFC chorus – which works just fine. Nevertheless, it’s Childs’ voice and vision which dominates “Jonny”, revisiting the stylistic highpoints of his old band as if guided by the gentle encouragement of Blake to do what he does best. Hence there are slightly dazed country songs – “I’ll Make Her My Best Friend”, “English Lady” – which recapture the somewhat autumnal whimsy of late Gorkys. There are daft glam songs which sound like the themes to ‘70s children’s programmes: “Wich Is Wich” and “Cave Dance”, the latter running off into a long and burbling drone-out which imbalances the whole album in a likeably perverse way. Best of all, the surging “Goldmine” and the prancing falsetto piano piece, “Bread”, sound like they could have been made around the same time as “The Game Of Eyes” and “Miss Trudy”. A very comforting album, really, and even the “Rubber Soul” pastiche, “Waiting Around For You” works perfectly, to the extent I keep expecting them to sing “Beep beep yeah” at any moment.

Spent a sizeable part of yesterday afternoon grappling again with “The Age Of Adz”, with little progress. It made me think, beyond the Sufjan Stevens album, there have been a good few albums this year, eagerly anticipated by me, that I’ve ended up delicately avoiding talking about here. Big personal disappointments, in other words: The Hold Steady’s “Heaven Is Whenever” and the Black Mountain album, whose title I’ve momentarily forgotten, spring to mind.

Yoko Ono unveils Montagu Square Blue Plaque for John Lennon

Yoko Ono has unveiled an English Heritage blue plaque on the Montagu Square apartment that she shared with John Lennon.

The ground floor and basement flat residence 34 Montagu Square was initially bought by Ringo Starr and then rented out to Paul McCartney and Jimi Hendrix.

Lennon and Ono moved into the property in 1968, and went on to shoot the naked cover of ‘Two Virgins’ in the apartment.

“I am very honoured to unveil this blue plaque and thank English Heritage for honouring John in this way,” said Yoko.

“This particular flat has many memories for me and is a very interesting part of our history. In what would have been John‘s 70th year, I am grateful to you all for commemorating John and this particular part of his London life, one which spawned so much of his great music and great art.”

Latest music and film news on Uncut.co.uk.

Uncut have teamed up with Sonic Editions to curate a number of limited-edition framed iconic rock photographs, featuring the likes of Pink Floyd, Bob Dylan and The Clash. View the full collection here.

The Charlatans drummer Jon Brookes returns to action following brain tumour

The Charlatans‘ drummer Jon Brookes has played with the band for the first time since being diagnosed with and treated for a brain tumour in September.

The drummer collapsed while onstage with the band in Philadelphia, and has been receiving treatment in the UK since then. On Saturday (October 23), he played during the encore of The Charlatans‘ set at the O2 Academy Birmingham.

Writing on Thecharlatans.net after the gig, Brookes admitted that he was feeling nervous ahead of the show.

“A huge feeling of goodwill came head-on towards me as over 2,000 Charlatans fans let me know that I was welcome back onstage,” he wrote.

He added: “I took the deepest breath and tried to let it flow. I hope it sounded OK, but to be honest I have no real measure, it was like I would imagine doing the 100 metres in the Olympic games would feel like! But please let me say thanks again to the Academy crowd for a top night!”

Brookes said that although he “won’t be doing much travelling this side of Christmas” he is “feeling strong and positive”.

The Verve‘s Pete Salisbury has been filling in for Brookes at The Charlatans‘ gigs while he is out of action.

Latest music and film news on Uncut.co.uk.

Uncut have teamed up with Sonic Editions to curate a number of limited-edition framed iconic rock photographs, featuring the likes of Pink Floyd, Bob Dylan and The Clash. View the full collection here.

Jimmy Page’s £495 autobiography sells out

A limited edition photographic autobiography from the Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page has sold out - despite not being officially released yet. 'Jimmy Page By Jimmy Page' – which cost £495 – is 512 pages long and features over 650 images of Page from throughout his career. It sold out through pre-orders. The hefty book is bound in leather and wrapped in silk and was compiled by Page himself, who also wrote the text. A selection of pictures from the book, taken by photographers such as Kate Simon, Neal Preston, Ross Halfin and Pennie Smith will be on display on November 5-6 at Elms Lester Painting Rooms in Covent Garden, London. Latest music and film news on Uncut.co.uk. Uncut have teamed up with Sonic Editions to curate a number of limited-edition framed iconic rock photographs, featuring the likes of Pink Floyd, Bob Dylan and The Clash. View the full collection here.

A limited edition photographic autobiography from the Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page has sold out – despite not being officially released yet.

‘Jimmy Page By Jimmy Page’ – which cost £495 – is 512 pages long and features over 650 images of Page from throughout his career. It sold out through pre-orders.

The hefty book is bound in leather and wrapped in silk and was compiled by Page himself, who also wrote the text.

A selection of pictures from the book, taken by photographers such as Kate Simon, Neal Preston, Ross Halfin and Pennie Smith will be on display on November 5-6 at Elms Lester Painting Rooms in Covent Garden, London.

Latest music and film news on Uncut.co.uk.

Uncut have teamed up with Sonic Editions to curate a number of limited-edition framed iconic rock photographs, featuring the likes of Pink Floyd, Bob Dylan and The Clash. View the full collection here.

THE ARBOR

Directed by Clio Barnard

Starring Manjinder Virk, Christine Bottomley

Andrea Dunbar was a success story of modern British drama – and one of its tragedies.

Best known to film audiences as writer of Alan Clarke’s Rita, Sue And Bob Too! (1986), Dunbar grew up on an impoverished Bradford estate and established herself, through the Royal Court, as a vital voice of working-class Britain.

However, she died at 29, after a drink-related decline.

Shot on the Bradford estate where she lived, Clio Barnard’s film documents its subject’s life and career, but beyond that, it paints a portrait of a family, a community and a harsh period of modern British history.

Named after Dunbar’s first play and her old street, The Arbor is as much imaginative essay as documentary, with actors lip-synching to the voices of real people – among them, the writer’s daughter, Lorraine.

The effect, distractingly artificial at first, serves to make this distressing story all the more immediate. Revealing, moving and entirely individual.

Jonathan Romney

SUFJAN STEVENS – THE GENIUS OF ADZ

If you’re hoping to hear the next instalment of Sufjan Stevens’s “50 States Project” – his homage to Rhode Island, perhaps, with songs about the flooding of Scituate and the Gaspée Affair – then you may be waiting a long time. Stevens recently admitted that his pledge to record an album dedicated to every State in the Union was merely a promotional gimmick, although in the light of his erratic output since Illinois – Uncut’s second-best album of the year, 2005 – you kinda wish he’d stuck with the programme. Certainly Rhode Island, or even North Dakota, would have been preferable to The BQE, his multimedia paean to a Brooklyn flyover, or yet another volume of Christmas songs. Music For Insomnia, an album of ambient frittering recorded with his stepdad, at least made good on its promise to lull listeners to sleep. Last month, Stevens suddenly announced he was streaming a new – hour-long! – EP via his Bandcamp page, yet All Delighted People did little to dispel the impression that here was a major artist struggling to regain his focus. It certainly had its moments of trademark Sufjan sublimity, but these were overshadowed by two versions of the rococo title track and a moving ode to his little sister that could only be reached via a petulant ten-minute guitar solo. Now at last comes the official follow-up to Illinois, although it makes All Delighted People feel like a triumph of brevity and restraint. The concept, unusually for Stevens, is that there is no concept. Aside from the title track, which was inspired the apocalyptic collages of schizophrenic folk artist Royal Robertson, this is Stevens writing from the heart. Gone are the Biblical allusions and potted local histories, replaced by meditations on love, sex, ageing and regret, and a fairly brutal excavation of his own neuroses. The downside of Stevens’ inward journey is that it seems to have eroded his confidence, leading to a maddening tendency to sabotage his best tunes. “Futile Devices” is a deceptively sweet and sparing opener, but it’s followed by the (aptly-titled) “Too Much” – the first of several ostensibly pretty songs to be sunk by a tsunami of electronic glitches and orchestral over-indulgence. “I Want To Be Well” does a pretty good job of conveying the mental trauma Stevens suffered during a recent bout of debilitating depression, which is to say it’s virtually unlistenable. Rather than use synthetic beats to lend his music muscle and drive, Stevens treats his drum machines like toys, programming them full of antsy, ungroovy rhythms. Initially, he’d planned to avoid using any live instruments on the record whatsoever, but instead an unhappy compromise has been brokered. Strings, horns, harps and choirs are sliced and diced on the computer, Stevens acting the mad conductor as he triggers torrents of queasy glissando with a click of his mouse. Yet when he calls off the artillery, The Age Of Adz can be stunning. Final track “Impossible Soul”, encapsulates everything that is brilliant and exasperating about this album (and, arguably, Stevens’s career as a whole). Over the course of its 25 astonishing minutes, it evokes in turn Lennon’s Double Fantasy, Radiohead’s In Rainbows, Ne-Yo, Bon Iver, Matmos, and The Langley Schools Music Project version of “I’m Into Something Good”. Stevens begins the track in a loved-up rapture, before gradually picking apart the whole business of love and finally batting his eyelids furiously at anyone in sight. “Girl, I want nothing less than pleasure,” he purrs, as the song-suite flutters toward a dreamy conclusion. “Boy, we made such a mess together…” Hang on, “boy” as in a boy, or “boy” as in American for blimey? At last, Stevens sounds like he’s having fun. Despite much speculation, he’s never come out as either gay or straight, so the matter remains tantalisingly unresolved. As indeed does the question about whether he is one of the most important songwriters of his generation or just an infuriating, neurotic show-off. This album provides plenty of evidence for both arguments. Sam Richards Q+A Who is Royal Robertson and how did he influence the album? He was a Louisiana-based sign-maker and self-proclaimed prophet who suffered from schizophrenia and created weird art that was inspired by his prophetic visions. A lot of his art is centered around spaceships, the Apocalypse, alien monsters and a pantheon of cosmic characters. These songs are preoccupied with primal things – love, heartache, wellness, sexual desire, loneliness, basic needs. But, like Royal, they have this cosmic veneer, this obsession with vast abstractions of the universe. It’s a big hodgepodge. Why did you choose to write this album from a more personal perspective? Everything I write is personal. I don’t think this album is any more or less personal. I would call it more primal, more rudimentary. Maybe it feels more so because I finally I let go of all the conceptual outfits. I guess I got tired of the whole literary narrative approach. It seemed time to narrow the content and focus more on impulse, on instinct. That’s what everyone else is doing, singing about love and sex, letting it all hang out. Why can’t I? You’re quite hard on yourself in the lyrics… I’ve become more and more suspicious of my own motivations. I used to believe in some kind of redemption, but I’ve been abused too many times to invest confidence in anyone, especially myself. I’d rather not dwell on self-deprecating anthems, but these songs have got the best of my insecurities. INTERVIEW: SAM RICHARDS

If you’re hoping to hear the next instalment of Sufjan Stevens’s “50 States Project” – his homage to Rhode Island, perhaps, with songs about the flooding of Scituate and the Gaspée Affair – then you may be waiting a long time. Stevens recently admitted that his pledge to record an album dedicated to every State in the Union was merely a promotional gimmick, although in the light of his erratic output since Illinois – Uncut’s second-best album of the year, 2005 – you kinda wish he’d stuck with the programme.

Certainly Rhode Island, or even North Dakota, would have been preferable to The BQE, his multimedia paean to a Brooklyn flyover, or yet another volume of Christmas songs. Music For Insomnia, an album of ambient frittering recorded with his stepdad, at least made good on its promise to lull listeners to sleep.

Last month, Stevens suddenly announced he was streaming a new – hour-long! – EP via his Bandcamp page, yet All Delighted People did little to dispel the impression that here was a major artist struggling to regain his focus. It certainly had its moments of trademark Sufjan sublimity, but these were overshadowed by two versions of the rococo title track and a moving ode to his little sister that could only be reached via a petulant ten-minute guitar solo. Now at last comes the official follow-up to Illinois, although it makes All Delighted People feel like a triumph of brevity and restraint.

The concept, unusually for Stevens, is that there is no concept. Aside from the title track, which was inspired the apocalyptic collages of schizophrenic folk artist Royal Robertson, this is Stevens writing from the heart. Gone are the Biblical allusions and potted local histories, replaced by meditations on love, sex, ageing and regret, and a fairly brutal excavation of his own neuroses.

The downside of Stevens’ inward journey is that it seems to have eroded his confidence, leading to a maddening tendency to sabotage his best tunes. “Futile Devices” is a deceptively sweet and sparing opener, but it’s followed by the (aptly-titled) “Too Much” – the first of several ostensibly pretty songs to be sunk by a tsunami of electronic glitches and orchestral over-indulgence. “I Want To Be Well” does a pretty good job of conveying the mental trauma Stevens suffered during a recent bout of debilitating depression, which is to say it’s virtually unlistenable.

Rather than use synthetic beats to lend his music muscle and drive, Stevens treats his drum machines like toys, programming them full of antsy, ungroovy rhythms. Initially, he’d planned to avoid using any live instruments on the record whatsoever, but instead an unhappy compromise has been brokered. Strings, horns, harps and choirs are sliced and diced on the computer, Stevens acting the mad conductor as he triggers torrents of queasy glissando with a click of his mouse.

Yet when he calls off the artillery, The Age Of Adz can be stunning. Final track “Impossible Soul”, encapsulates everything that is brilliant and exasperating about this album (and, arguably, Stevens’s career as a whole). Over the course of its 25 astonishing minutes, it evokes in turn Lennon’s Double Fantasy, Radiohead’s In Rainbows, Ne-Yo, Bon Iver, Matmos, and The Langley Schools Music Project version of “I’m Into Something Good”.

Stevens begins the track in a loved-up rapture, before gradually picking apart the whole business of love and finally batting his eyelids furiously at anyone in sight. “Girl, I want nothing less than pleasure,” he purrs, as the song-suite flutters toward a dreamy conclusion. “Boy, we made such a mess together…” Hang on, “boy” as in a boy, or “boy” as in American for blimey? At last, Stevens sounds like he’s having fun. Despite much speculation, he’s never come out as either gay or straight, so the matter remains tantalisingly unresolved.

As indeed does the question about whether he is one of the most important songwriters of his generation or just an infuriating, neurotic show-off. This album provides plenty of evidence for both arguments.

Sam Richards

Q+A

Who is Royal Robertson and how did he influence the album?

He was a Louisiana-based sign-maker and self-proclaimed prophet who suffered from schizophrenia and created weird art that was inspired by his prophetic visions. A lot of his art is centered around spaceships, the Apocalypse, alien monsters and a pantheon of cosmic characters. These songs are preoccupied with primal things – love, heartache, wellness, sexual desire, loneliness, basic needs. But, like Royal, they have this cosmic veneer, this obsession with vast abstractions of the universe. It’s a big hodgepodge.

Why did you choose to write this album from a more personal perspective?

Everything I write is personal. I don’t think this album is any more or less personal. I would call it more primal, more rudimentary. Maybe it feels more so because I finally I let go of all the conceptual outfits. I guess I got tired of the whole literary narrative approach. It seemed time to narrow the content and focus more on impulse, on instinct. That’s what everyone else is doing, singing about love and sex, letting it all hang out. Why can’t I?

You’re quite hard on yourself in the lyrics…

I’ve become more and more suspicious of my own motivations. I used to believe in some kind of redemption, but I’ve been abused too many times to invest confidence in anyone, especially myself. I’d rather not dwell on self-deprecating anthems, but these songs have got the best of my insecurities.

INTERVIEW: SAM RICHARDS

ELTON JOHN AND LEON RUSSELL – THE UNION

In the mid-’60s, while the teenage piano player Reg Dwight was breaking into showbiz, Leon Russell was building his rep as a top-flight LA session man and a key member of the legendary Wrecking Crew. The transplanted Oklahoman was also the ringleader of LA’s Southern mafia, a talented, hard-living posse of musicians that included Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett, Gram Parsons, Dr John and fellow Tulsa natives JJ Cale, Jim Keltner and Chuck Blackwell, intermittently infiltrated by honorary shitkickers George Harrison, Eric Clapton, Keith Richards and Mick Jagger. One night in August 1970, soon after he’d completed his job as the musical director of Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs & Englishmen, Russell was among the curious folks packed into the Troubadour on Santa Monica Boulevard to check out a much-hyped young Brit, now renamed Elton John. Russell was impressed, and the feeling was mutual. “I copied Leon Russell, and that was it,” Elton admitted in 1971. Russell’s influence is readily apparent on rollicking uptempo songs like “Take Me To The Pilot”, “Amoreena” and “Honky Cat”. And when Elton broke in America it was with “Your Song”, the kissin’ cousin of Russell’s exquisite love ballad, “A Song For You”. All of that makes The Union, Elton’s heartfelt, T Bone Burnett-curated attempt to give Russell his due, a matter of payback as well as a tribute. Not surprisingly, Elton and lyricist Bernie Taupin, with Russell frequently alongside them, chose to revisit the rustic terrain of Tumbleweed Connection, and their romantically imagined America locks in seamlessly with the 68-year-old Russell’s deep grounding in the real thing. A number of these freshly minted tunes would have fitted comfortably onto any of Elton’s early-’70s classics or Russell’s self-titled 1971 debut album, while the culminating “Never Too Old (To Hold Somebody)” and “The Hand Of Angels” reflect back on those days with a mix of “been there, done that” satisfaction and valedictory nostalgia. The material is designed to showcase the principals’ piano playing, and skilled engineer Mike Piersante has set up the mic’ing and mix by putting Russell’s piano on one side of the stereo spectrum, Elton’s on the other, making the record a particular kick under headphones. Some of these cuts, including the adrenalised “Monkey Suit”, were built on top of basic tracks containing only Russell and Elton’s pianos, played perfectly in sync with each other. “No one uses two pianos on a record anymore, since Phil Spector, probably,” Elton noted. More often than not during its 63-minute length, The Union sounds like an Elton John album, thanks to his signature melodies enwrapping Taupin’s image-filled lyrics, his still-powerful voice and undiminished presence. Only through repeated listenings does Russell’s Hoagy Carmichael-like lazy drawl assert itself, as he sings with disarming poignancy and tenderness, his always-grainy voice now as rutted as a dirt road. (Russell, it should be noted, underwent brain surgery shortly before the sessions began.) For Burnett, who obsessively pursues aural authenticity, this expansive project – with its gospel choir, brass section and an all-star cast including Booker T Jones on Hammond organ and Robert Randolph on pedal steel, along with the producer’s own wrecking crew – is the antithesis of his monophonic, single-mic recording of John Mellencamp’s recent No Better Than This. The arrangements come closer to excess than any of Burnett’s recent productions – perilously close at times. There’s an over-abundance of ballads, some of which feel more ponderous than reflective, and wall-to-wall choral carpeting thickens passages that call out for spare, close-mic’ed intimacy. But these missteps are counter-balanced by the galloping rock’n’boogie of “Hey Ahab”, “A Dream Come True”, “Monkey Suit”, “Hearts Have Turned To Stone” and the elegiac resonance of “Jimmie Rodgers’ Dream”. The most captivating slow-tempoed song is Taupin’s Civil War fable “Gone To Shiloh”, which plays out as a brass-encrusted New Orleans funeral march. Russell takes the first verse and Elton the third, bookending an appearance by Neil Young in a spine-tingling cameo. The pomp of the arrangement almost befits a Broadway production number, and yet its sheer gut impact is immense. If “Gone To Shiloh” isn’t the sort of track you’d go to on a regular basis, it seems tailor-made for special occasions. And that’s perfectly fitting, as this gathering of old-timers with something still to say, if not to prove, seems special indeed. Bud Scoppa

In the mid-’60s, while the teenage piano player Reg Dwight was breaking into showbiz, Leon Russell was building his rep as a top-flight LA session man and a key member of the legendary Wrecking Crew.

The transplanted Oklahoman was also the ringleader of LA’s Southern mafia, a talented, hard-living posse of musicians that included Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett, Gram Parsons, Dr John and fellow Tulsa natives JJ Cale, Jim Keltner and Chuck Blackwell, intermittently infiltrated by honorary shitkickers George Harrison, Eric Clapton, Keith Richards and Mick Jagger.

One night in August 1970, soon after he’d completed his job as the musical director of Joe Cocker’s Mad Dogs & Englishmen, Russell was among the curious folks packed into the Troubadour on Santa Monica Boulevard to check out a much-hyped young Brit, now renamed Elton John. Russell was impressed, and the feeling was mutual. “I copied Leon Russell, and that was it,” Elton admitted in 1971. Russell’s influence is readily apparent on rollicking uptempo songs like “Take Me To The Pilot”, “Amoreena” and “Honky Cat”. And when Elton broke in America it was with “Your Song”, the kissin’ cousin of Russell’s exquisite love ballad, “A Song For You”.

All of that makes The Union, Elton’s heartfelt, T Bone Burnett-curated attempt to give Russell his due, a matter of payback as well as a tribute. Not surprisingly, Elton and lyricist Bernie Taupin, with Russell frequently alongside them, chose to revisit the rustic terrain of Tumbleweed Connection, and their romantically imagined America locks in seamlessly with the 68-year-old Russell’s deep grounding in the real thing. A number of these freshly minted tunes would have fitted comfortably onto any of Elton’s early-’70s classics or Russell’s self-titled 1971 debut album, while the culminating “Never Too Old (To Hold Somebody)” and “The Hand Of Angels” reflect back on those days with a mix of “been there, done that” satisfaction and valedictory nostalgia.

The material is designed to showcase the principals’ piano playing, and skilled engineer Mike Piersante has set up the mic’ing and mix by putting Russell’s piano on one side of the stereo spectrum, Elton’s on the other, making the record a particular kick under headphones. Some of these cuts, including the adrenalised “Monkey Suit”, were built on top of basic tracks containing only Russell and Elton’s pianos, played perfectly in sync with each other. “No one uses two pianos on a record anymore, since Phil Spector, probably,” Elton noted.

More often than not during its 63-minute length, The Union sounds like an Elton John album, thanks to his signature melodies enwrapping Taupin’s image-filled lyrics, his still-powerful voice and undiminished presence. Only through repeated listenings does Russell’s Hoagy Carmichael-like lazy drawl assert itself, as he sings with disarming poignancy and tenderness, his always-grainy voice now as rutted as a dirt road. (Russell, it should be noted, underwent brain surgery shortly before the sessions began.)

For Burnett, who obsessively pursues aural authenticity, this expansive project – with its gospel choir, brass section and an all-star cast including Booker T Jones on Hammond organ and Robert Randolph on pedal steel, along with the producer’s own wrecking crew – is the antithesis of his monophonic, single-mic recording of John Mellencamp’s recent No Better Than This. The arrangements come closer to excess than any of Burnett’s recent productions – perilously close at times. There’s an over-abundance of ballads, some of which feel more ponderous than reflective, and wall-to-wall choral carpeting thickens passages that call out for spare, close-mic’ed intimacy. But these missteps are counter-balanced by the galloping rock’n’boogie of “Hey Ahab”, “A Dream Come True”, “Monkey Suit”, “Hearts Have Turned To Stone” and the elegiac resonance of “Jimmie Rodgers’ Dream”.

The most captivating slow-tempoed song is Taupin’s Civil War fable “Gone To Shiloh”, which plays out as a brass-encrusted New Orleans funeral march. Russell takes the first verse and Elton the third, bookending an appearance by Neil Young in a spine-tingling cameo. The pomp of the arrangement almost befits a Broadway production number, and yet its sheer gut impact is immense. If “Gone To Shiloh” isn’t the sort of track you’d go to on a regular basis, it seems tailor-made for special occasions. And that’s perfectly fitting, as this gathering of old-timers with something still to say, if not to prove, seems special indeed.

Bud Scoppa

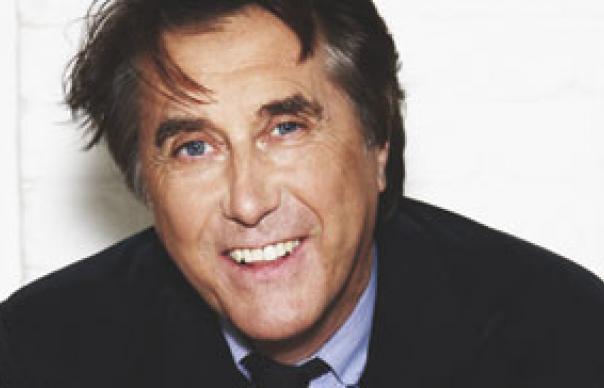

BRYAN FERRY – OLYMPIA

“Take me on a rollercoaster / Take me on an airplane ride...” From the start Bryan Ferry was bewitched by the exotic glamour of pop, its promise of some fabulous elsewhere, “far beyond the pale horizon, some place near the desert strand”. But if he once conjured with the contradictions of dream homes and heartaches, in later years he seemed to elide the difference between the real and make-believe and take refuge in misty never-neverlands: Avalon, Mamouna, the Hollywood Casablanca of “As Time Goes By”. On the face of it Olympia might be the latest station on this wistful tour: vaguely redolent of deco movie palaces or even a Leni Riefenstahl-style propaganda spectacle. Until you realise that it’s likely a more prosaic reference to the West Kensington neighbourhood, all exhibition halls and office blocks, where you find Ferry’s studio. And indeed rather than some great departure, Ferry’s first album of original material since 2002’s Frantic sticks pretty close to home. Neurotically so: just like Frantic, Olympia draws heavily on material originally recorded back in 1996 with Dave Stewart (conspicuously absent from the stellar list of names – Scissor Sisters, Eno, Nile Rodgers, Jonny Greenwood, David Gilmour – highlighted in the advance publicity). At least three tracks here – “You Can Dance”, “Alphaville”, and the closing “Tender Is the Night” – date from those sessions, while the Scissor Sisters collaboration, the coyly titled “Heartache By Numbers”, was apparently recorded over five years ago. And yet Olympia was trailed with such promise. First DJ Hell had stripped down “You Can Dance” to a chilly techno pulse, recasting Ferry as the vampiric crooner we once knew from Roxy tracks like “Ladytron”. Then Groove Armada hit upon one of their seemingly random moments of genius, cutting up Ferry with Truffaut and reworking “Shameless” into a brooding electraglide in blue. Finally Leo Zero joined the dots from Godard to Daft Punk, rerecording “Alphaville” as relentless Parisian funk. All three versions worked brilliantly at reclaiming Ferry as the founding retrofuturist of British avant-pop, but none appear on the album as it now arrives. Instead “You Can Dance” (which in the 1996 version available on bootlegs was actually a curious essay in drum and bass), is draped in the gilded, otiose funk that’s been Ferry’s signature soundworld since 1985’s Boys And Girls – perfectly rendered in the accompanying video, which is like if Gustav Klimt had directed a Robert Palmer promo. In many ways it’s an awesome production – nobody except Sade dares to make records that sound so impeccably imperious any more. But listen to it against the Hellish remix and its finery pales. The tendency to overload and overwork the song, the result of too many hours of Olympian fretting, comes to a head on the cover of Tim Buckley’s “Song To The Siren”. The track credits five guitarists, including Nile Rodgers, Phil Manzanera, David Gilmour and Jonny Greenwood – Eric Clapton and Johnny Marr were presumably out of the country – three drummers, a percussionist, and Brian Eno playing some obscure synth, and the result is a stupendously overblown gas giant of a cover, one that’s simply blown away by Liz Fraser and Robin Guthrie’s spare Mortal Coil version. Ferry clearly realises this – it’s why he enjoys his breezy cocktail jazz outings and bar band Dylan dalliances. And the best tracks on Olympia benefit from a certain lightness of touch: “Me Oh My” fans the embers of torch song – “Everything I care about is gone/I wonder why?” – and makes a virtue of the husk of Ferry’s lunar croon. And the closing “Tender Is The Night” taps into Ferry’s familiar F Scott Fitzgerald feel for fading romance; like Gatsby, enchanted by the green light of promise but, like “Boats against the current/Borne back ceaselessly into the past”. Olympia could do with a little more of that future-facing yearning, the contemporary spirit that crackled through the remixes, to remind us of times when Ferry seemed as much a figure from our future as from our recent past. Stephen Trousse

“Take me on a rollercoaster / Take me on an airplane ride…” From the start Bryan Ferry was bewitched by the exotic glamour of pop, its promise of some fabulous elsewhere, “far beyond the pale horizon, some place near the desert strand”.

But if he once conjured with the contradictions of dream homes and heartaches, in later years he seemed to elide the difference between the real and make-believe and take refuge in misty never-neverlands: Avalon, Mamouna, the Hollywood Casablanca of “As Time Goes By”. On the face of it Olympia might be the latest station on this wistful tour: vaguely redolent of deco movie palaces or even a Leni Riefenstahl-style propaganda spectacle. Until you realise that it’s likely a more prosaic reference to the West Kensington neighbourhood, all exhibition halls and office blocks, where you find Ferry’s studio.

And indeed rather than some great departure, Ferry’s first album of original material since 2002’s Frantic sticks pretty close to home. Neurotically so: just like Frantic, Olympia draws heavily on material originally recorded back in 1996 with Dave Stewart (conspicuously absent from the stellar list of names – Scissor Sisters, Eno, Nile Rodgers, Jonny Greenwood, David Gilmour – highlighted in the advance publicity). At least three tracks here – “You Can Dance”, “Alphaville”, and the closing “Tender Is the Night” – date from those sessions, while the Scissor Sisters collaboration, the coyly titled “Heartache By Numbers”, was apparently recorded over five years ago.

And yet Olympia was trailed with such promise. First DJ Hell had stripped down “You Can Dance” to a chilly techno pulse, recasting Ferry as the vampiric crooner we once knew from Roxy tracks like “Ladytron”. Then Groove Armada hit upon one of their seemingly random moments of genius, cutting up Ferry with Truffaut and reworking “Shameless” into a brooding electraglide in blue. Finally Leo Zero joined the dots from Godard to Daft Punk, rerecording “Alphaville” as relentless Parisian funk.

All three versions worked brilliantly at reclaiming Ferry as the founding retrofuturist of British avant-pop, but none appear on the album as it now arrives. Instead “You Can Dance” (which in the 1996 version available on bootlegs was actually a curious essay in drum and bass), is draped in the gilded, otiose funk that’s been Ferry’s signature soundworld since 1985’s Boys And Girls – perfectly rendered in the accompanying video, which is like if Gustav Klimt had directed a Robert Palmer promo. In many ways it’s an awesome production – nobody except Sade dares to make records that sound so impeccably imperious any more. But listen to it against the Hellish remix and its finery pales.

The tendency to overload and overwork the song, the result of too many hours of Olympian fretting, comes to a head on the cover of Tim Buckley’s “Song To The Siren”. The track credits five guitarists, including Nile Rodgers, Phil Manzanera, David Gilmour and Jonny Greenwood – Eric Clapton and Johnny Marr were presumably out of the country – three drummers, a percussionist, and Brian Eno playing some obscure synth, and the result is a stupendously overblown gas giant of a cover, one that’s simply blown away by Liz Fraser and Robin Guthrie’s spare Mortal Coil version.

Ferry clearly realises this – it’s why he enjoys his breezy cocktail jazz outings and bar band Dylan dalliances. And the best tracks on Olympia benefit from a certain lightness of touch: “Me Oh My” fans the embers of torch song – “Everything I care about is gone/I wonder why?” – and makes a virtue of the husk of Ferry’s lunar croon. And the closing “Tender Is The Night” taps into Ferry’s familiar F Scott Fitzgerald feel for fading romance; like Gatsby, enchanted by the green light of promise but, like “Boats against the current/Borne back ceaselessly into the past”.

Olympia could do with a little more of that future-facing yearning, the contemporary spirit that crackled through the remixes, to remind us of times when Ferry seemed as much a figure from our future as from our recent past.

Stephen Trousse

Bryan Ferry talks to The Mighty Boosh about his new album

The Mighty Boosh‘s Noel Fielding has spoken to Bryan Ferry about his new solo album ‘Olympia’.

The pair spoke ahead of the Roxy Music man releasing his new record on Monday (October 25) – at the studio where Ferry recorded the LP in a video interview with NME.

The chat sees them talk about comedy and Roxy Music‘s classics gigs and fans, plus Fielding discovers that his hero’s first ever gig was actually a unique moment in rock ‘n’ roll history, Bill Haley And The Comets‘ first ever European tour.

“There was a Radio Luxembourg competition and I won it, it was two front row seats, and it was the first rock ‘n’ roll tour where the Teddy Boys congregated and went down and wrecked the seats,” recalls Ferry. “It was amazing, I was only 10. I took my big sister.”

Asked by Fielding if he was “quite frightened ” by the violence, Ferry replied: “No I was quite up for it! I was sitting in my school blazer just watching.”

Watch [url=http://www.nme.com/news/the-mighty-boosh/53530] Noel Fielding talking to Bryan Ferry now[/url].

Antony & The Johnsons’ Antony Hegarty hints at quitting touring

Antony And The Johnsons frontman Antony Hegarty has hinted that he may never tour again.

The singer admitted that it took him a year to recover from touring his last 2009 album ‘The Crying Light’, which left him burnt out and exhausted.

“This last year I haven’t travelled at all,” he told The Independent. “I’ve been in a quandary – I have a problem with the amount of travelling there is, so it’s a huge issue. And does that mean I’m never going to tour again? I don’t really know.”

Hegarty, who recently released his latest album ‘Swanlights’, has yet to line-up any tour dates in support of his current LP other than a show with the Orchestra Of St Luke‘s at the Alice Tully Hall Starr Theater on New York‘s Broadway on October 30.

“It took me a year to recover,” he added. “It wrings out the marrow from your bones. I remember Devandra Banhart once told me, ‘I feel like a piece of charcoal’. When you’ve poured everything out and there’s nothing left, you feel like a piece of coal.”

Hallogallo 2010: London Barbican, October 21, 2010

A couple of days ago, I asked here whether anyone had seen the Michael Rother & Friends/Hallogallo 2010 show yet. Olmanal was one person who responded. The show in Ghent was great, he said, but noted, “‘Deluxe (Immer Wieder)’ with Steve Shelley pounding away on the drums, may not be exactly how you remember it.” Watching Rother, Shelley and bassist Aaron Mullan (listed as from Tall Firs, though I prefer his other band, Glass Rock) at the Barbican in London last night, Olmanal’s warning turned out to be something of an understatement. When “Deluxe” hoves into view, you can still pick out that immeasurably beautiful, serene melody from the Harmonia original. But around it, the music is much more bombastic and heavy, and it feels as if the grace has been sacrificed for quite a lot of rock heft. This turns out to be the plot for most of the show. Michael Rother, encamped behind a desk with laptop, water bottles and FX, begins a song with a splutter of electronics and loops, then carves out a frictional, meaty version of one of his strafed riffs. Shelley locks into a generally steroidal version of motorik, so loud that it often dwarfs Rother’s work. Aaron Mullan, mainly, is hard to pick up. At times, the sound they make is genuinely rousing. But more often (and I suspect, judging by most reactions, that I’m very much in the minority with the caveats), it leaves me a little frustrated. There’s much to be admired in Rother’s treatment of his old songs as open-ended; that their arrangements shouldn’t be preserved in aspic, but allowed to evolve over the years. If we continue to celebrate Neu! as a forward-thinking band, it stands to reason we should applaud Rother for handling his mighty consistent music in a contemporary way. But I have to say, I prefer the clean lines and elegant simplicity of the originals to what amounts, cruelly, as a technobludgeoning. “Silberstreif”, for example, still begins with one of those lovely, twanging lines that Rother perfected on his early solo albums. Again and again, though, Shelley’s drumming leaves the delicacies in his dust. He’s a tremendous player, no doubt, and parts of the show feel like a celebration of his resolute, linear pummelling. But for some reason, he plays in a very mechanical way – following the “endless line”, for sure, but in a muscular and somewhat mechanical fashion which misses the bounce – the funkiness, of sorts – provided by Klaus Dinger and Jaki Liebezeit. I kept thinking what a different, lighter tack Joe Dilworth, from Th’Faith Healers and Stereolab, would’ve brought to the show. I have a hunch why Hallogallo 2010 sounds like this, and it comes down not to Shelley’s technique (God knows I’ve seen him play much more subtly many times over the years with Sonic Youth), but to Rother’s musical preferences over the past few years. Time and again, Rother has talked about his love of Secret Machines (Ben Curtis, once of that band, even figured in an early version of Hallogallo 2010, I think), and consequently, he seems to have reconfigured many of his quicksilver old tunes in the thudding image of that band; a kind of bruising, stadium rock revamp of motorik, and not one I particularly liked. It’s only in the encore, really, that the approach totally works for me, when Hallogallo 2010 have a go at one of Neu!’s heaviest, most grinding tunes, “Negativland”. Here, the faintly industrial scrapes, the sheet metal guitar sound, are tremendously effective, and Shelley and Mullan are brilliant at pulling off the lurching changes of speed that punctuate the piece. For the rest: well, I guess I’m just a bit of a lightweight.

A couple of days ago, I asked here whether anyone had seen the Michael Rother & Friends/Hallogallo 2010 show yet. Olmanal was one person who responded. The show in Ghent was great, he said, but noted, “‘Deluxe (Immer Wieder)’ with Steve Shelley pounding away on the drums, may not be exactly how you remember it.”

Laura Marling: ‘I’m not releasing two albums this year now’

Laura Marling has revealed that she is now not going to release two albums this year – but the extra time will make her third album better.

The singer, who features in the 2010 [url=http://www.nme.com/coollist]NME Cool List[/url], [url=http://www.nme.com/news/laura-marling/49306]had originally planned to release a second album in 2010, following the release in March of her second record ‘I Speak Because I Can'[/url].

However Marling now says fans will have to wait a little bit longer for her next release.

“It’s not going to be this year, but it’s good,” she explained. “It will be on its way soon, which is nice. It’s becoming different from the last album actually, because I’ve scrapped a bit of it halfway through. I hope to have it done by February. Setting deadlines is not my favourite thing!”

To see where Marling is in this year’s Cool List and for an exclusive interview get this week’s issue of NME on UK newsstands, or available digitally worldwide right now.

U2 recruit Danger Mouse to produce new album

U2 frontman Bono has revealed that Danger Mouse is working on their forthcoming album.

The record, which is tentatively titled ‘Songs Of Ascent’ and is [url=http://www.nme.com/news/u2/53482]due out next year according to the band’s manager Paul McGuinness [/url], has been produced by the Gnarls Barkley and Broken Bells man, otherwise known as Brian Burton.

“We have about 12 songs with him,” Bono told Theage.com. “At the moment that looks like the album we will put out next, because it’s just happening so easily.”

The singer also revealed that the band are currently working on two other albums, the first of which is a “club” record featuring Lady Gaga collaborator RedOne, Black Eyed Peas‘ Will.i.am and David Guetta.

“U2‘s remixes in the 1990s were a real treasure,” he said. “So we wanted to make a club sounding record. We have a pile of songs.”

The band are also hoping to make a concept album based on songs Bono and guitarist The Edge have written for their Spider-Man musical, [url=http://www.nme.com/news/faithless–2/52501]which opens on Broadway next month[/url].

“We haven’t convinced the rest of the band to do that yet,” added the singer. “[Drummer] Larry [Mullen Jr] definitely has a raised eyebrow.”

The Slits’ Ari Up dies aged 48

The Slits‘ frontwomen Ari Up has died at the age of 48.

The singer – real name Arianna Forster – passed away yesterday (October 20).

News of her death was confirmed by the Sex Pistols and PiL frontman John Lydon, who is married to Forster‘s mother. He delivered the news about her death on his website.

“John[Lydon] and Nora [Forster] have asked us to let everyone know that Nora‘s daughter Arianna – aka Ari-Up – died today (October 20) after a serious illness,” was posted on JohnLydon.com. “She will be sadly missed. Everyone at JohnLydon.com and PiLofficial.com would like to pass on their heartfelt condolences to John, Nora and family. Rest in Peace.”

Forster formed The Slits in 1976 at the age of 14. They released two albums, 1979’s ‘Cut’ and 1981’s ‘Return Of The Giant Slits’, before splitting up.

She later went on to release a solo album called ‘Dread More Dan Dead’ in 2005, among other projects, before reforming The Slits later that year.

Johnny Marr has been among those to pay tribute to Up, posting on Twitter: “Respect to Ari Up. The Slits played with The Cribs last year and she was great.”

Rolling Stones’ Keith Richards: ‘Mick Jagger is still a great friend’

The Rolling Stones‘ Keith Richards has insisted that he is still “great friends” with Mick Jagger, despite branding the singer “unbearable” in his new book.

The guitarist admitted that his bandmate was angry about certain sections of his autobiography, Life, but they are still close pals.

“He was a bit peeved about this and that,” Richards told Rollingstone.com. “[But] Mick and I are still great friends and still want to work together. Can you imagine if life went along smoothly and everybody agreed? Nothing would happen. There’d be no blues.”

The guitarist added that the pair have even talked about more activity from The Rolling Stones in 2011.

Richards‘ comments come after [url=http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/51942/220045]he recently admitted in an interview that the pair do not get on[/url], branding the singer “Brenda” and “Your Majesty”.

He also admitted that he not been in Jagger‘s dressing room for more than 20 years.

Life is set to be released on October 26.

The Fall’s Mark E Smith: ‘I threw a bottle at Mumford & Sons’

The Fall‘s Mark E Smith has claimed that he threw a bottle at Mumford And Sons at a recent festival.

The singer said that he took matters into his own hands because he did not like the sound of Marcus Mumford and the gang warming up their vocals.

“We were playing a festival in Dublin the other week,” he told Australian magazine Brag. “There was this other group warming up in the next sort of chalet, and they were terrible.”

He added: “I said, ‘Shut them cunts up,’ and they were still warming up, so I threw a bottle at them. The band said, ‘That’s the Sons Of Mumford [sic] or something, they’re Number Five in charts!’. I just thought they were a load of retarded Irish folk singers.”

The Fall and Mumford And Sons were both on the bill for the Electric Picnic festival, which took place near Dublin last month.