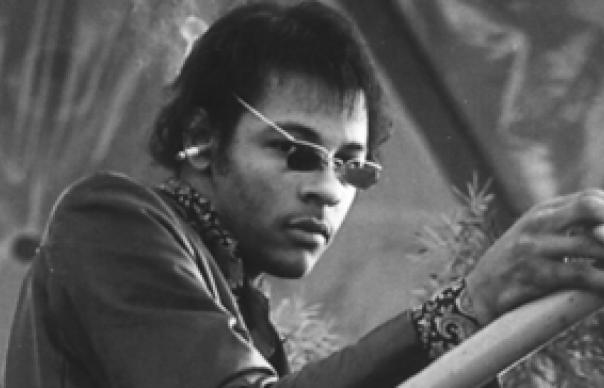

Love’s 1967 masterstroke, Forever Changes, was a monster to live up to, and Arthur Lee knew it. An intoxicating mix of hope and hate, ebullience and paranoia, shifting perspectives and orchestral beauty, it sprang from the Summer Of Love with a mysterious elegance and wisdom all too rare in pop.

It wasn’t a commercial breakthrough, though, and instead of rallying the group behind its genius, the classic 1966-68 Love lineup (featuring crucial second songwriter Bryan MacLean) imploded in a haze of recrimination, drug abuse, and legal trouble. Lee retrenched, carrying on under the Love banner, but he could never have replicated the magic of Forever Changes, even if he’d been foolish enough to try.

Thus began one of rock’s more peculiar odysseys – Arthur Lee’s downward spiral from shaman to burnout, from Sunset Strip’s most resplendent hipster to just another lost hippy soul sleepwalking through the ’70s. Beginning with Forever Changes’ 1969 follow-up, Four Sail, Lee’s recordings proffered ever-dwindling returns.

Aided by a succession of musically adroit yet ininspired backing musicians, Love plummeted into hippy jams and anonymous hard rock, callow pop and perfunctory forays into R’n’B. Even the best of it wasn’t traceable back to the man responsible for “The Red Telephone” and “Seven And Seven Is.”

Lee remained a powerful singer, though, and glimmers of the old magic occasionally surfaced. But the songwriting was half-baked and mundane. It was as if the maelstrom had stripped Arthur of his identity. One would be hard-pressed to find a more precipitous artistic drop-off in all rock’n’roll than 1967’s Forever Changes to 1974’s Reel To Real.

Love Lost, Sundazed’s surprise unearthing of all-but-forgotten 1971 session tapes (laid down during the band’s brief alliance with Columbia Records), throws a fascinating wrinkle into Love’s disintegration. Veering from captivating to frustrating, charming to maddening, it’s a typically uneven set. Yet there are moments of sheer beauty, and Lee clearly poured his heart into the grooves. Reinventing himself in the image of his recently deceased friend Jimi Hendrix, interweaving blazing rock with sublime, fly-on-wall acoustic tracks, Dear You, as the Columbia album was to be called, had enough mojo to fuel a plausible comeback.

Evidence that Hendrix’s death hit Arthur Lee hard lurks everywhere – in his vocal phrasing and spoken asides, in guitarist Craig Tarwater’s high-voltage riffs, in the souped-up bluesy arrangements. In fact, if imitation is the highest form of flattery, Love Lost could be interpreted as a Hendrix tribute album par excellence (although, to be fair, bits of Cream, Mountain, the Jeff Beck Group, and others percolate throughout). “I Can’t Find It”, which with a bit more work might have been the single, echoes “The Wind Cries Mary”; the stuttering strut of “Midnight Sun” is drenched in Electric Ladyland-isms. And on and on.

These are fine efforts – vicarious pleasures to be sure – that nonetheless get under your skin. “Product Of The Times” even gets away from stock paeans to troubled love affairs for a bit of self-reflective commentary, a flicker of Lee’s old songwriting spark. “Product,” riding a gutbucket riff and some sizzling lead guitar, and everyman anthem “Everybody’s Gotta Live”, given a hair-raising Lee vocal, are impassioned, fully realised gems.

Yet, for all the group’s chutzpah, Arthur Lee‘s indulgences – a tendency to over-sing into a screech, some cringeworthy misogyny – blunt the impact. Curiously, Columbia assigned no producer for these sessions, terminating the band’s contract without releasing a note. A clearheaded producer, one capable of adding some discipline, focus and editing, might well have crafted Dear You into a remarkable rebirth.

For all Lee’s bluster, though, the austere power of Love Lost‘s acoustic cuts suggest the hard-rock moves sabotaged his natural talent and melodic gifts. “He Said She Said”, a springy shuffle with flashing Dylanesque imagery, sparkles with a spontaneity and freshness the electric cuts can’t touch. Album opener “Love Jumped Through My Window”, Lee’s soulful tenor soaring over some choppy guitar runs, is pure joy. It’s a tempered direction Lee should have explored more.

Love Lost was, in effect, Arthur Lee’s last true creative songwriting burst. Despite Columbia’s abandonment of the project, Lee hardly gave up on this body of work, revisiting 12 of its 14 songs, on Vindicator (his 1972 hard-rock turn on A&M), 1973’s Black Beauty (recorded for the short-lived Buffalo Records but never released), and Reel To Real (Love’s last major-label fling, an R’n’B-flavoured set on Robert Stigwood’s RSO Records in 1974). Lee’s career truly unspooled thereafter: a few archival releases, an ill-fated 1978 reunion with Bryan MacLean, and only very occasional half-hearted rehabilitations. From 1996 to 2001, Lee served time in a California prison, just another troublemaker caught up in the state’s controversial so-called “three strikes” law.

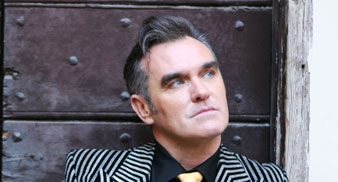

But unlike, say, Syd Barrett or Skip Spence, Lee managed a hardly expected, entirely revelatory comeback, beginning in 2002. Making peace with the incandescence of Elektra-era Love, Lee raced the clock, making up for nearly three lost decades in five short years. Resuming his alliance with a hungry, young Love – LA garage band Baby Lemonade – Lee played Hollywood and criss-crossed Europe, sometimes adding string and horn sections in breathtaking recreations of Forever Changes. In a familiar echo of Lee’s mercurial past, it was as if the hard-rock-and-Hendrix-obsessed Love circa 1968-74 – and Love Lost – had never existed.

Luke Torn