Not for now, just for forever. Insurgent Country’s big bang…

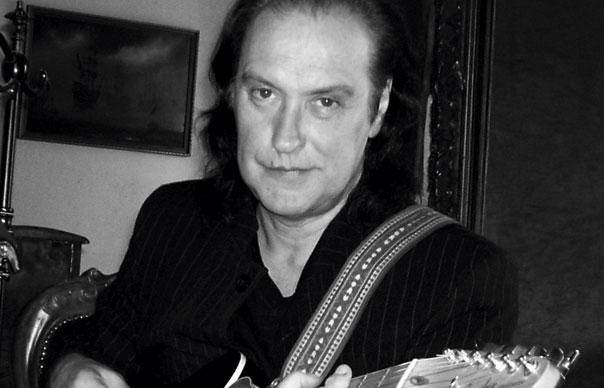

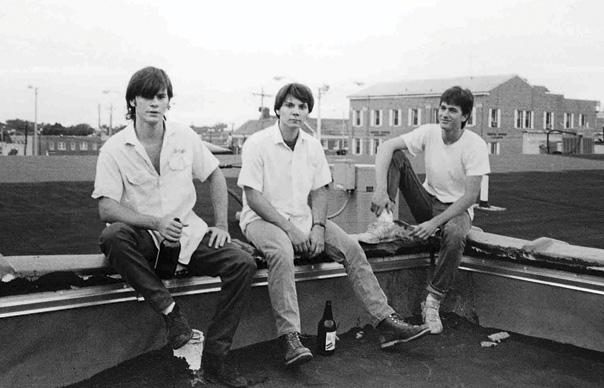

They were still wet behind the ears in 1987, barely into their twenties, but Belleville, Illinois trio Uncle Tupelo (guitarist Jay Farrar, bassist Jeff Tweedy, drummer Mike Heidorn) had been woodshedding in various combinations around St. Louis for years, first as upstart rockabillies (the Plebes), later as garage/punk acolytes (the Primitives). Soaking up every conceivable influence, they spun out everything: Nuggets-style ‘60s garage tunes, indie rock (leaning, especially, on the styles of the Replacements, Green on Red, and the Minutemen), the folk and folk-rock of Dylan and the Byrds, blues and hardcore country.

By the time their first true original songs arrived, though, they were beyond it all, and asking the hard questions; fun time was over. Or, as Tweedy later snapped in an interview: “This was not a game.”

“Before I Break,” “Screen Door,” and “Whiskey Bottle,” grim vignettes laid down on lo-fi cassettes (and included here as alternate takes), ushered in a tidal wave of brutally honest material documenting—and defying—hopelessness, of being trapped with a nowhere life in a nowhere town. The songs, focused treatises on poverty and the search for meaning, were immersed in booze and disillusionment, tapping deep into the tattered psyche of Ronnie Reagan’s now decimated ‘City on a Hill’ generation. “Well, time won’t wait, better open the gate,” Farrar barks out, in a rush of words on No Depression’s opening blast, “Graveyard Shift.” “Get up and start what needs to be done.”

These sentiments could be delivered in a gale-force rush of explosive electric guitar, noisy slabs of rhythm, and tricky, stop-on-a-dime time changes. Or, alternatively—and stunningly—with a wistful, floating melody dug out from A.P. Carter’s dusty songbooks, accented by banjo, mandolin, fiddles, pedal steel, and gorgeous two-part harmonies. Both methods were equally devastating.

This almost randomized reconnection to America’s deepest musical roots was timely. Mainstream country music, abandoning all self-respect, had transmogrified into something truly ghastly. Embracing line dancing, big hats, and a new generation of crossover stars — Garth Brooks, Billy Ray Cyrus — they kicked Cash, Buck, Merle, and Possum to the curb. Blue-collar indie rock was on the run, too, soon to be subsumed into the pop mainstream in the post-Nirvana years. No Depression—mixing, on one hand, age-old sentiments of trial and trouble with urgent, cut-throat punk rock and, on the other, age-old musical styles with contemporary yearning for a better life—felt revelatory, inspirational, real.

Plenty of others — Jason & the Scorchers, the Blasters, Rank and File — had been pounding it out for years, searching for, among other things, common ground between the Clash and George Jones. But Tupelo’s ability to reclaim the very fabric of American music, especially its distressed, hardscrabble underpinnings, to personalize it, and shepherd it into the conscience of a new generation, well, that was a different thing entirely. By the mid-1990s, youngsters like Whiskeytown, Old ’97s, and Gillian Welch, rediscovered treasures like Lucinda Williams and Billy Joe Shaver, even legendary old-timers — like Johnny Cash — were in ascension.

Produced by Paul Kolderie and Sean Slade, fresh off work with indie heroes Dinosaur Jr., No Depression was out as summer 1990 dawned. Farrar was indisputably band’s visionary at this point, handling most of the singing and writing. “Graveyard Shift”, “Before I Break” and “Whiskey Bottle” flying by in an adrenalin rush, were the hardest hitters, swinging at a pugilistic sonic presentation the band would, inevitably, drift away from. Slightly scaled-back, subtler numbers, though, like “Outdone” and the Tweedy-written “That Year,” were just as affecting. The beatific title cut, of course, a cover of the Carter Family’s soul-searching, spirit-seeking gem, was a stroke of genius.

This expanded edition appends 22 tracks, including a dozen cuts from those primordial cassettes—highlighted by a fine acoustic version of the Flying Burrito Brothers‘ “Sin City”. The crown jewel, though, is Not Forever, Just for Now, a 10-song demo assembled for record-label attention in 1989. All the major No Depression material is here, fully formed, plus a fateful, forgotten masterpiece—”I Got Drunk”—fusing dark, galloping bluegrass hues to an all-too-familiar protagonist drinking himself into oblivion. With a fluid, gutsy sound leaning ever so slightly toward power pop, the start-stop, punch-in-the-face dynamics of the official versions are (slightly) less pronounced here, as if they’re not trying quite so hard. A blistering portrait of the group just uncovering the breadth of their power.

Luke Torn

Q&A

Mike Heidorn

You had garage-band roots; where did the country influences come from?

The punk rock, the garage rock was definitely the common element that Jeff and Jay had. Jay’s family and his upbringing lent itself to the acoustic instruments by way of the Missouri Ozarks [his mother’s home], a very rural area southwest of Belleville. But his folks had banjos—I remember going there as a 14-year-old—fiddles, harmonicas, pianos, acoustic guitars galore. Jeff, his upbringing brought acoustic [instruments] to the family gatherings. I think he had some uncles who played country, so those two were in touch with the country. When they brought those acoustic guitars and harmonicas to band practice, that was really fascinating. It was like ‘Hell, we can do all these things!’

A lot of these songs, the restlessness and frustration, still resonate now, really hold up…

I think that while Jeff was right behind him, that premise from Jay’s lyrics really hit home with me as an individual living in Belleville. The lyric that personified Uncle Tupelo for many years—well other than “On liquor I’ll spend my last dime” (from “Before I Break”) was from the song “Whiskey Bottle”: “not forever, just for now,” in other words, there’s a life out there, a life worth living. Those songs seemed so real to me. It was like these guys were really looking around.

What strikes me is how the early Tupelo songs connect to the past, into age-old emotions, yet played for a very young crowd?

I think if you’d have tried to purposely study how to do that, you’d have failed! The future takes its course…

INTERVIEW: LUKE TORN