Reunited band rides a wave of serendipity in a surprising, deeply satisfying return... The stars aligned for Graham Parker in early 2011, when he impetuously reformed The Rumour 31 years after they’d last played as a unit. Shortly thereafter, he was contacted by filmmaker Judd Apatow, a longtime fan of Parker’s music, who asked the artist to act and perform in the movie he was working on, This Is 40, setting up a dramatically increased profile for the reunion. Not only that, but the recording sessions provided a dramatic climax for the Gramaglia Brothers’ feature-length documentary Don’t Ask Me Questions, a recounting of Parker’s career. And all this nearly 20 years after Parker, having been dropped from his last major label deal, reinvented himself as a DIY artist, still “searching for that fool’s gold”, his signature pissed-off snarl and cynical attitude reassuringly intact. When he first emerged in 1976, Parker updated and recontextualized the ’50s archetype of the English Angry Young Man at the perfect moment – the dawn of the punk revolution. Together with the newly formed Rumour – keyboard player Bob Andrews and guitarist Brinsley Schwartz, both formerly of the group that bore the latter’s name, ex-Ducks Deluxe guitarist Martin Belmont and the young rhythm section of bassist Andrew Bodnar and drummer Steve Goulding – Parker immediately secured his place in the vanguard of the new movement. Heat Treatment, the band’s debut album – produced by Nick Lowe, another Brinsleys alumnus – formed a bridge between pub rock and punk rock, as Parker kicked open the door for fellow angry young man Elvis Costello, who’d show up in ’77. Though G.P. And The Rumour never rose above cult status, the band’s four ’70s albums, topped off by 1979’s certified classic Squeezing Out Sparks, are as hard-hitting and eloquent as any series of LPs issued during that vital half-decade. The group recorded just one more LP, 1980’s The Up Escalator, before disbanding, whereupon Parker began his extended second act, frequently working with ex-Rumour members along the way. So how does this seminal ’70s band translate to the Internet Age? Quite naturally, it turns out. Tackling Parker’s material with immediacy and masterful finesse, the reunited players show no signs of rust – and this despite the fact that Schwartz has spent recent years working as a luthier at Chandler’s in London, while Belmont has been employed as a librarian in Yorkshire. Parker and his mates forcefully reclaim their turf with the fittingly vitriolic opener “Snake Oil Capital Of The World”, as Parker nicks the intro of Howlin’ Wind’s “Don’t Ask Me Questions” – a cosmic coincidence considering that he wrote these songs with no clue he’d be recording them with The Rumour. What’s immediately apparent is that this veteran has continued to evolve as a singer, no longer reliant on the primal howl that characterized him early on. On the following pair of midtempo cruisers, “Long Emotional Ride” and “Stop Cryin’ About The Rain”, both album highlights, the band’s economical playing leaves Parker plenty of space to explore the nuances of the song and the shadings his earthily elegant mature voice. This sort of knowing interaction animates the entire album, which has a refreshingly spontaneous feel, the result of their cutting the dozen songs live, including Parker’s vocals. Parker isn’t the only one who shines on this labour of love, as the band casually but emphatically occupies its sweet spot. Schwartz shows throughout that he’s one of rock’s most underrated song-serving guitarists. Witness his appropriately sinuous line through “Snake Oil Capital Of The World”, or his central riff on the title track, slurred notes burnishing an arching, evocative arpeggio as timeless as the song’s premise. Andrews is consistently effective in his supporting role, his Garth Hudson-like organ vamps enclosing the other instruments like a down comforter. And the Dylanesque “Coathangers”, the album’s most aggressive track, is distinguished by a taut, tasty ensemble performance, all six bandmembers clearly reveling in the fact that they’re waking up the echoes. When Parker sings in “Long Emotional Ride”, “Maybe I’m just getting old or something/But Something broke down my resistance/And opened the door”, the lines come across with the force of an epiphany. This prescient statement undoubtedly took on further resonance for Parker and his band as serendipity afforded them a welcome chance to once again squeeze out sparks together – though the enduring effect is one of warmly glowing embers. Bud Scoppa Q&A Graham Parker How did the reunion come about? Very simple, really. It just popped into my mind that Steve and Andrew would be really something as the rhythm section on my next record. I emailed both of them, and Steve said, “Why not get Martin, Bob and Brinsley as well? That would be a proper band… Kidding!” I stopped thinking then and started emailing people – because if you think about these things, you won’t do it. The next day, I was like, “What have I done?” You already had the songs written? Yeah. My first thought was, “What do these songs have to do with The Rumour?” But I never wrote any of those records for the band; I just wrote the songs. When did Judd Apatow get hold of you? No more than two weeks later. He said part of the movie would be about an indie label, and I would be the kind of artist this label would sign. I said, “Guess what? I’ve just reformed The Rumour.” He flew us all out to LA to do a two-day shoot. You can’t make this stuff up. We were onstage together for the first time in 31 years in this fabulous theatre with a film crew and excellent lunches – that was the best part. Brinsley was amazed that anyone would want to hear us. Did Apatow have any direct involvement with the album? He got this award-winning designer to do the cover, and the guy made this crazy cover that looks like gay Christian rock! When I saw it, I thought, “Oh my God, that is terrifying.” INTERVIEW: BUD SCOPPA

Reunited band rides a wave of serendipity in a surprising, deeply satisfying return…

The stars aligned for Graham Parker in early 2011, when he impetuously reformed The Rumour 31 years after they’d last played as a unit. Shortly thereafter, he was contacted by filmmaker Judd Apatow, a longtime fan of Parker’s music, who asked the artist to act and perform in the movie he was working on, This Is 40, setting up a dramatically increased profile for the reunion. Not only that, but the recording sessions provided a dramatic climax for the Gramaglia Brothers’ feature-length documentary Don’t Ask Me Questions, a recounting of Parker’s career. And all this nearly 20 years after Parker, having been dropped from his last major label deal, reinvented himself as a DIY artist, still “searching for that fool’s gold”, his signature pissed-off snarl and cynical attitude reassuringly intact.

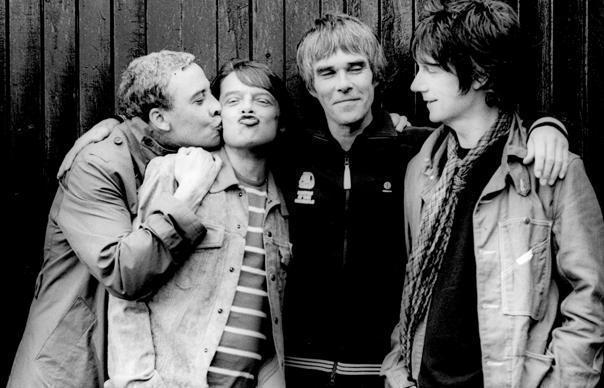

When he first emerged in 1976, Parker updated and recontextualized the ’50s archetype of the English Angry Young Man at the perfect moment – the dawn of the punk revolution. Together with the newly formed Rumour – keyboard player Bob Andrews and guitarist Brinsley Schwartz, both formerly of the group that bore the latter’s name, ex-Ducks Deluxe guitarist Martin Belmont and the young rhythm section of bassist Andrew Bodnar and drummer Steve Goulding – Parker immediately secured his place in the vanguard of the new movement. Heat Treatment, the band’s debut album – produced by Nick Lowe, another Brinsleys alumnus – formed a bridge between pub rock and punk rock, as Parker kicked open the door for fellow angry young man Elvis Costello, who’d show up in ’77. Though G.P. And The Rumour never rose above cult status, the band’s four ’70s albums, topped off by 1979’s certified classic Squeezing Out Sparks, are as hard-hitting and eloquent as any series of LPs issued during that vital half-decade. The group recorded just one more LP, 1980’s The Up Escalator, before disbanding, whereupon Parker began his extended second act, frequently working with ex-Rumour members along the way.

So how does this seminal ’70s band translate to the Internet Age? Quite naturally, it turns out. Tackling Parker’s material with immediacy and masterful finesse, the reunited players show no signs of rust – and this despite the fact that Schwartz has spent recent years working as a luthier at Chandler’s in London, while Belmont has been employed as a librarian in Yorkshire. Parker and his mates forcefully reclaim their turf with the fittingly vitriolic opener “Snake Oil Capital Of The World”, as Parker nicks the intro of Howlin’ Wind’s “Don’t Ask Me Questions” – a cosmic coincidence considering that he wrote these songs with no clue he’d be recording them with The Rumour. What’s immediately apparent is that this veteran has continued to evolve as a singer, no longer reliant on the primal howl that characterized him early on. On the following pair of midtempo cruisers, “Long Emotional Ride” and “Stop Cryin’ About The Rain”, both album highlights, the band’s economical playing leaves Parker plenty of space to explore the nuances of the song and the shadings his earthily elegant mature voice. This sort of knowing interaction animates the entire album, which has a refreshingly spontaneous feel, the result of their cutting the dozen songs live, including Parker’s vocals.

Parker isn’t the only one who shines on this labour of love, as the band casually but emphatically occupies its sweet spot. Schwartz shows throughout that he’s one of rock’s most underrated song-serving guitarists. Witness his appropriately sinuous line through “Snake Oil Capital Of The World”, or his central riff on the title track, slurred notes burnishing an arching, evocative arpeggio as timeless as the song’s premise. Andrews is consistently effective in his supporting role, his Garth Hudson-like organ vamps enclosing the other instruments like a down comforter. And the Dylanesque “Coathangers”, the album’s most aggressive track, is distinguished by a taut, tasty ensemble performance, all six bandmembers clearly reveling in the fact that they’re waking up the echoes.

When Parker sings in “Long Emotional Ride”, “Maybe I’m just getting old or something/But Something broke down my resistance/And opened the door”, the lines come across with the force of an epiphany. This prescient statement undoubtedly took on further resonance for Parker and his band as serendipity afforded them a welcome chance to once again squeeze out sparks together – though the enduring effect is one of warmly glowing embers.

Bud Scoppa

Q&A

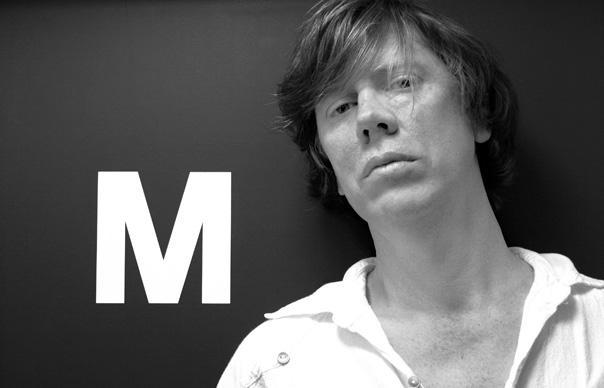

Graham Parker

How did the reunion come about?

Very simple, really. It just popped into my mind that Steve and Andrew would be really something as the rhythm section on my next record. I emailed both of them, and Steve said, “Why not get Martin, Bob and Brinsley as well? That would be a proper band… Kidding!” I stopped thinking then and started emailing people – because if you think about these things, you won’t do it. The next day, I was like, “What have I done?”

You already had the songs written?

Yeah. My first thought was, “What do these songs have to do with The Rumour?” But I never wrote any of those records for the band; I just wrote the songs.

When did Judd Apatow get hold of you?

No more than two weeks later. He said part of the movie would be about an indie label, and I would be the kind of artist this label would sign. I said, “Guess what? I’ve just reformed The Rumour.” He flew us all out to LA to do a two-day shoot. You can’t make this stuff up. We were onstage together for the first time in 31 years in this fabulous theatre with a film crew and excellent lunches – that was the best part. Brinsley was amazed that anyone would want to hear us.

Did Apatow have any direct involvement with the album?

He got this award-winning designer to do the cover, and the guy made this crazy cover that looks like gay Christian rock! When I saw it, I thought, “Oh my God, that is terrifying.”

INTERVIEW: BUD SCOPPA