Although the World Trade Center bombings have been scrutinised in unsparing and forensic media detail, Hollywood has been conspicuously slow off the mark to get involved. Five years on from 9/11 itself, Oliver Stone’s drama – drawn from the real life testimonies of two New York Port Authority cops extracted from the rubble of Ground Zero – is only the second film, after United 93 earlier this year, to directly address the 21st century’s inaugural act of man-made terror. Hollywood studios are often slow and cautious when responding to hot button events like 9/11. For sure, there are already a handful of films that have been informed, to varying degrees, by the attack on the Twin Towers – Fahrenheit 9/11, 25th Hour, War Of The Worlds, even Munich. Yet the fear of alienating great swathes of audience demographics and incurring political censure for tackling this explicitly sensitive issue sends studios scurrying back to their comfort zone of rom-coms, costume dramas and comic book adaptations. Matters presumably are further complicated by daily news broadcasts detailing the latest dispatches from President Bush’s vituperative and ill-conceived response to the tragedy – the rollercoaster-to-Armageddon commonly referred to as the War on Terror.

Which perhaps explains how United 93 came to be: although bankrolled by Universal, the director, Paul Greengrass, is Irish and the project was developed by Working Title – the English production company best known for Four Weddings And A Funeral. What makes World Trade Center so interesting as the first, full-blooded American take on 9/11 is that Oliver Stone isn’t the obvious candidate to helm a film like this. Although Stone has a lengthy history of on-screen political engagement – Salvador, the Vietnam trilogy, JFK, Nixon, his Castro and Arafat documentaries – his film-making style is traditionally too bombastic to handle a subject that’s still so raw and painful for many Americans. But Stone has made what might be, if the critical reception to World Trade Center in America can be believed, the most successful film of his career. Ironic, perhaps, as it appears to share little in common with any other movie on his CV. There’s no trademark Stone masonry, no great sound and fury (unless you count the breath-taking sequence around the 40 minute mark where the Towers come down), none of the dizzying, sensory overload you expect from the man who made Natural Born Killers. Stone opts for a straightforward approach to this story, which has led some to churlishly suggest World Trade Center is little better than a made-for-TV movie. Arguably, this demonstrates a fundamental lack of understanding of Stone – a great liberal humanist – and is also extraordinarily ungenerous to a movie that’s both commemorative and elegiac in its handling of an event which led to the deaths of 2,749 people, approximately 400 of whom were from the emergency services, there simply to do their job and save lives. Cage is perfect here. He does a great Jimmy Stewart: his John McLoughlin is an Everyman, just doing what he’s got to do, whatever it takes, no heroics, no showboating.

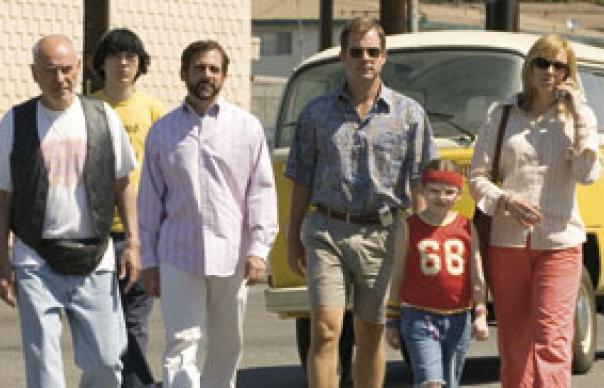

Stone – like Greengrass – elects to focus solely on the specific events as they unfold. He doesn’t acknowledge the wider context of what drove a group of religious fundamentalists to hijack four aeroplanes with the intention of flying them into high-profile targets on American soil. At its heart, World Trade Center is solely about two men struggling to survive in extraordinary, hellish circumstances. And, to Stone’s infinite credit, it never descends into schmaltz. The first third of the movie finds McLoughlin and Jimeno gearing up for a day’s work – it’s rather prosaic, matter-of-fact, following a similar trajectory to Greengrass’ film which showed the doomed crew and passengers of United 93 as they went through the equally mundane routines of their own lives prior to embarkation. Once the Towers come down, Stone explores the effects of the disaster on their families. His shrewd casting of Gyllenhaal and Bello means we never once get hysteria, no wailing and gnashing of teeth, just a genuine, impactful sense of the uncertainty, the dreadful not-knowing, as they wait for news.

The most contentious character in all this is David Karnes (Michael J Shannon). A former Marine whose response to the catastrophe is to dust off his uniform and go to the site where, with an almost pathological single-mindedness, he yomps across the blasted, nightmare landscape on a one-man mission to find survivors. His two-dimensional, gung-ho fervour is decidedly out-of-synch with the rest of the movie’s more rounded characters, and you could argue he’s emblematic of the director’s most sledge-hammer tendencies. But he reflects a part of the American mindset, and his decision to re-enlist at the end of the film (in a postscript, we learn he’s served in the Philippines and Iraq) is based on a very real, clear-cut notion of patriotism.

World Trade Center is part of America’s healing process after 9/11. And at the risk of sounding trite, it’s also part of Stone’s own personal healing after the astonishing critical demolition of his last film, Alexander. Here, he’s made a humbling and moving movie about enduring against the odds. And for a director who’s frequently been misunderstood and misrepresented, this is a particular triumph he should savour.

MICHAEL BONNER