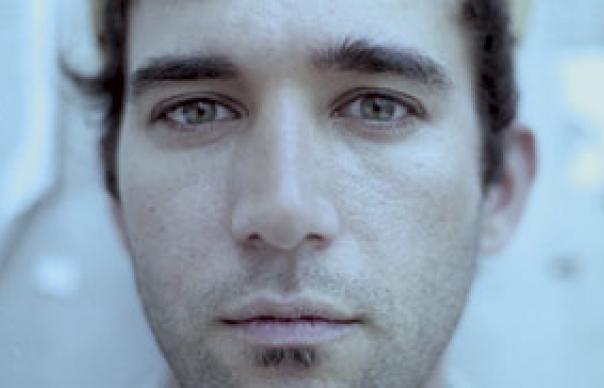

If you’re hoping to hear the next instalment of Sufjan Stevens’s “50 States Project” – his homage to Rhode Island, perhaps, with songs about the flooding of Scituate and the Gaspée Affair – then you may be waiting a long time. Stevens recently admitted that his pledge to record an album dedicated to every State in the Union was merely a promotional gimmick, although in the light of his erratic output since Illinois – Uncut’s second-best album of the year, 2005 – you kinda wish he’d stuck with the programme.

Certainly Rhode Island, or even North Dakota, would have been preferable to The BQE, his multimedia paean to a Brooklyn flyover, or yet another volume of Christmas songs. Music For Insomnia, an album of ambient frittering recorded with his stepdad, at least made good on its promise to lull listeners to sleep.

Last month, Stevens suddenly announced he was streaming a new – hour-long! – EP via his Bandcamp page, yet All Delighted People did little to dispel the impression that here was a major artist struggling to regain his focus. It certainly had its moments of trademark Sufjan sublimity, but these were overshadowed by two versions of the rococo title track and a moving ode to his little sister that could only be reached via a petulant ten-minute guitar solo. Now at last comes the official follow-up to Illinois, although it makes All Delighted People feel like a triumph of brevity and restraint.

The concept, unusually for Stevens, is that there is no concept. Aside from the title track, which was inspired the apocalyptic collages of schizophrenic folk artist Royal Robertson, this is Stevens writing from the heart. Gone are the Biblical allusions and potted local histories, replaced by meditations on love, sex, ageing and regret, and a fairly brutal excavation of his own neuroses.

The downside of Stevens’ inward journey is that it seems to have eroded his confidence, leading to a maddening tendency to sabotage his best tunes. “Futile Devices” is a deceptively sweet and sparing opener, but it’s followed by the (aptly-titled) “Too Much” – the first of several ostensibly pretty songs to be sunk by a tsunami of electronic glitches and orchestral over-indulgence. “I Want To Be Well” does a pretty good job of conveying the mental trauma Stevens suffered during a recent bout of debilitating depression, which is to say it’s virtually unlistenable.

Rather than use synthetic beats to lend his music muscle and drive, Stevens treats his drum machines like toys, programming them full of antsy, ungroovy rhythms. Initially, he’d planned to avoid using any live instruments on the record whatsoever, but instead an unhappy compromise has been brokered. Strings, horns, harps and choirs are sliced and diced on the computer, Stevens acting the mad conductor as he triggers torrents of queasy glissando with a click of his mouse.

Yet when he calls off the artillery, The Age Of Adz can be stunning. Final track “Impossible Soul”, encapsulates everything that is brilliant and exasperating about this album (and, arguably, Stevens’s career as a whole). Over the course of its 25 astonishing minutes, it evokes in turn Lennon’s Double Fantasy, Radiohead’s In Rainbows, Ne-Yo, Bon Iver, Matmos, and The Langley Schools Music Project version of “I’m Into Something Good”.

Stevens begins the track in a loved-up rapture, before gradually picking apart the whole business of love and finally batting his eyelids furiously at anyone in sight. “Girl, I want nothing less than pleasure,” he purrs, as the song-suite flutters toward a dreamy conclusion. “Boy, we made such a mess together…” Hang on, “boy” as in a boy, or “boy” as in American for blimey? At last, Stevens sounds like he’s having fun. Despite much speculation, he’s never come out as either gay or straight, so the matter remains tantalisingly unresolved.

As indeed does the question about whether he is one of the most important songwriters of his generation or just an infuriating, neurotic show-off. This album provides plenty of evidence for both arguments.

Sam Richards

Q+A

Who is Royal Robertson and how did he influence the album?

He was a Louisiana-based sign-maker and self-proclaimed prophet who suffered from schizophrenia and created weird art that was inspired by his prophetic visions. A lot of his art is centered around spaceships, the Apocalypse, alien monsters and a pantheon of cosmic characters. These songs are preoccupied with primal things – love, heartache, wellness, sexual desire, loneliness, basic needs. But, like Royal, they have this cosmic veneer, this obsession with vast abstractions of the universe. It’s a big hodgepodge.

Why did you choose to write this album from a more personal perspective?

Everything I write is personal. I don’t think this album is any more or less personal. I would call it more primal, more rudimentary. Maybe it feels more so because I finally I let go of all the conceptual outfits. I guess I got tired of the whole literary narrative approach. It seemed time to narrow the content and focus more on impulse, on instinct. That’s what everyone else is doing, singing about love and sex, letting it all hang out. Why can’t I?

You’re quite hard on yourself in the lyrics…

I’ve become more and more suspicious of my own motivations. I used to believe in some kind of redemption, but I’ve been abused too many times to invest confidence in anyone, especially myself. I’d rather not dwell on self-deprecating anthems, but these songs have got the best of my insecurities.

INTERVIEW: SAM RICHARDS