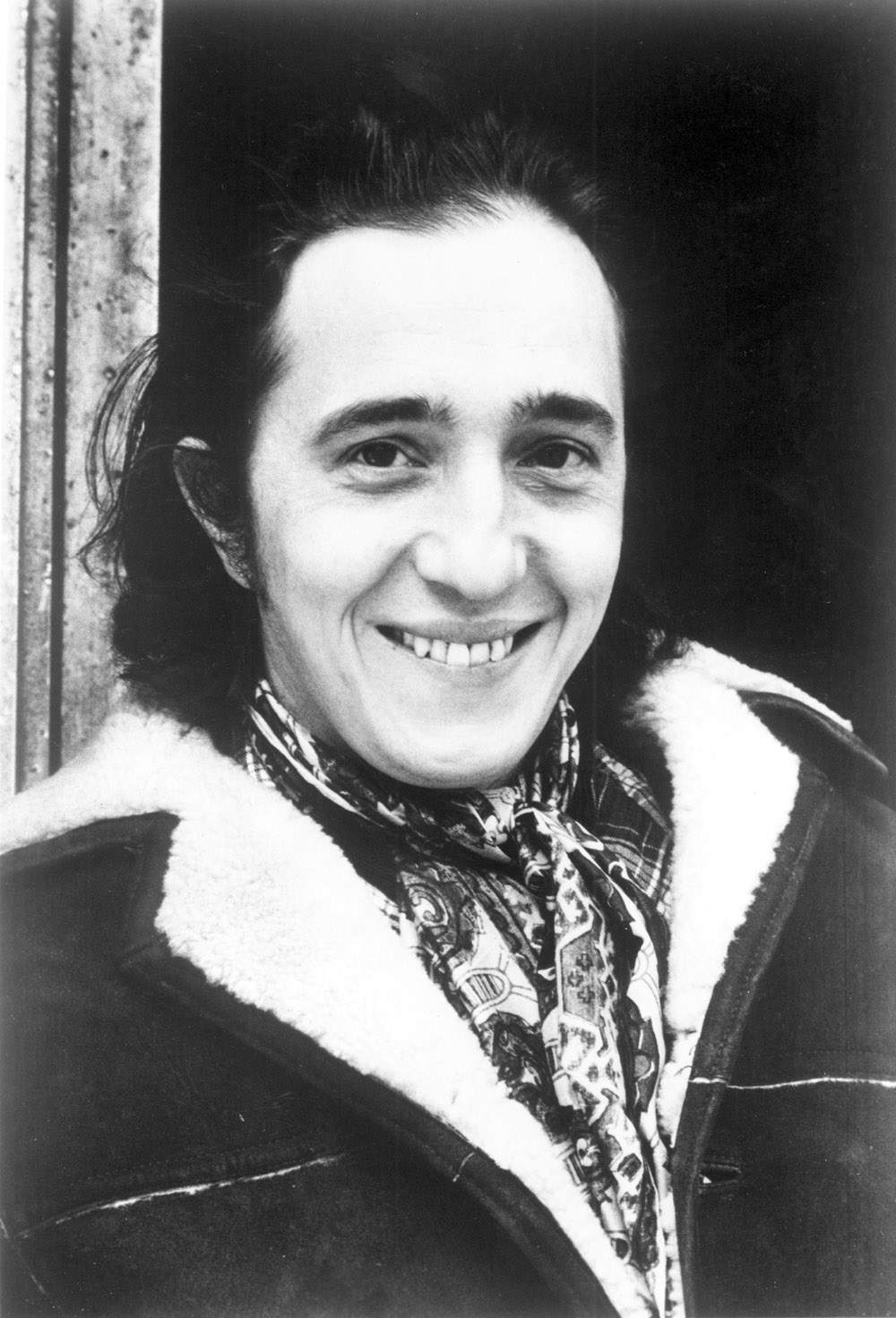

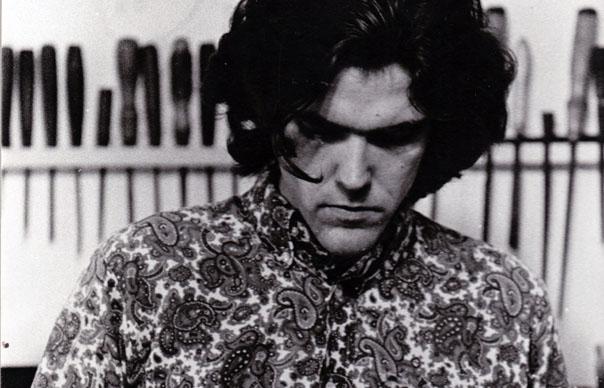

After spending last weekend catching up with what seems like a veritable deluge of great new music, I had a yen for some old favourites this weekend, among them two albums by the cult singer-songwriter, Paul Siebel, Woodsmoke & Oranges and Jack-Knife Gypsy.

It’s sadly probable that only a handful of people reading this will actually have heard of Siebel, let alone the music he made on these two incredible records. Originally released in 1970 and 1971, they quickly disappeared without trace, vinyl chimera, as did, soon after, Siebel, their charismatic author.

What acknowledgement they received at the time was unbelievably meagre, but often ecstatic. For those of us fortunate enough to have heard them on first release, these albums were testaments to a breathtaking talent, whose genius flared briefly, but brilliantly enough to be mentioned in the same breath as any of the songwriting legends who rode the folk and country rock booms of the 60s and early 70s, from Dylan to Gram Parsons. Much revered by his contemporaries, Siebel simply blew out of town after Jack-Knife Gypsy, destination: obscurity.

He was born in Buffalo, New York, in 1937, studied at the university there and later spent time in the US Army. By 1965, after serving a musical apprenticeship in the clubs and coffee houses in Buffalo, he was in Greenwich Village, playing the usual haunts. Inspired by Hank Williams and Dylan, he was also by now writing the brilliant songs that eventually got him signed to Elektra, who bankrolled the four three hour sessions it took to record Woodsmoke And Oranges.

With fiddles, acoustic guitars, occasional pedal steel and Siebel’s glorious voice to the fore, Woodsmoke’s honky tonk exuberance, backporch ruminations and broken-hearted ballads are more than passingly reminiscent of Gram Parsons’ first solo album, GP. It would be fair to say from some of these songs that Siebel’s view of love is somewhat more than jaundiced, and there’s a cruel misogynistic edge to songs like “Miss Cherry Lane” that wouldn’t be out of place in the Jagger-Richards’ songbook. More typical, however, of Siebel’s temperament, is the dream-like reverie of “Long Afternoons”, a requiem for lost love set to one of his most achingly affecting melodies – as keenly piercing as anything on Blood On The Tracks. Siebel also has an unflinching eye for the sad detail of emotional trauma.

And while the captivating “Then Came The Children” and the anti-war song “My Town” are lyrically allusive, powerfully allegorical, the best of his early songs – “Louise” and “Bride 1945” – are models of narrative clarity, deeply moving portraits of a lonely truckstop whore and a young war bride, the two women separately condemned to lives of mutual disappointment and serial unhappiness. If he’d never written anything else, these two songs alone would justify Siebel’s reputation as one of the finest songwriters of his time.

The people who heard it and got it loved Woodsmoke. . ., but it sold poorly. Elektra gave Siebel another chance, however, and with a band of crack session men – including Byrds’ guitarist Clarence White, David Grisman on mandolin, Buddy Emmons on pedal steel, drummer Russ Kunkel, Doug Kershaw, Sea Train’s Richard Greene – he recorded Jack-Knife Gypsy, which is by turns ravishing, forlorn, ecstatic, delirious and ultimately bleak beyond words.

Dylan’s influence is again enormous – especially on the dark and menacing title track and the surreal “Jasper And The Miners” – with Siebel revelling in the vernacular story-telling styles of The Basement Tapes and John Wesley Harding. Elsewhere, there’s the rhapsodic “Prayer Song”, the desperate “If I Could Stay” and – best of all – the desolate introspection of “Chips Are Down”, one of the most self-lacerating songs ever written, a bleak nugget, as soiled as Dylan’s “Dirge”.

Disappointed by poor sales, Siebel went into artistic decline, writer’s block giving way to addiction, depression and self-destruction. He was last heard of, in 1996, working as a bread-maker in a café in Maryland. We shouldn’t lament for too long his drift towards the edge of things, however, because over the course of these two albums Siebel recorded more good songs than most artists manage in a lifetime.

Elektra re-released Woodsmoke & Oranges and Jack-Knife Gypsy in 2004 as a double CD, after a long period out of catalogue. Miraculously, it’s still available or you can download them individually on iTunes for an incredibly reasonable £3.95 each. There’s also a third album, Live At McCabe’s, recorded in 1978 with guitarists David Bromberg and Gary White that you can also get easily enough from either Amazon or iTunes, that features tracks from his two studio albums as well as covers of “Lonesome House”, originally recorded in 1927 by Blind Lemon Jefferson, Hank Williams’ “I’m So Lonely I Could Cry” and Jimmie Rodgers’ “Woman Made A Fool Out Of Me” and “I’m In The Jailhouse Now”. Give them a listen, at least.

Have a good week.