Cosmic Cowboy’s indie label exhumed... Six years after his death, 47 years since his biggest hit (Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made For Walking”), Lee Hazlewood remains an enigma. Partly, he designed it that way. Throughout his career, he cast himself as an outsider, a drifter, a cowboy. What he didn’t quite accept, though the evidence is plentiful, is that in career terms he had a habit of shooting himself in the high-heeled boot. The label, LHI, was formed in 1966 when Hazlewood’s reputation was rising. Prior to his unlikely star-turn with Sinatra, the former DJ from Oklahoma had been round the block a couple of times; scoring a hit with Sanford Clark in 1956, and adding the echo to Duane Eddy’s twang. He had also laid the foundations of an idiosyncratic solo career with Trouble Is A Lonesome Town (1963) and The NSVIPs (1964). LHI took his ambition to another level, though it remains unclear just what Hazlewood wanted from the imprint. It can be viewed as one of the first great indie labels, though it was run from an office at 9000 Sunset Blvd with scant regard for commerce. Indeed, Suzi Jane Hokom, whose roles included production and art direction (as well as being romantically involved with Hazlewood) suggests the boss wasn’t bothered about hits. He ran a label because others were prepared to fund it. Still, he gave his co-conspirators free rein, and strange things happened, even if few people noticed. Hokom was allowed to develop as a producer, and used her influence to get the International Submarine Band signed, though Hazlewood was at best ambivalent about Gram Parsons. (Hokom suggests his disinterest was, at root, based on jealousy). A relaxed, chaotic endeavour, LHI had an open door approach, and a studio band comprised of key members of The Wrecking Crew (guitarist Al Casey was an associate from Hazlewood’s time as a DJ in Phoenix), with back-up from the likes of future-Byrd Clarence White and Ry Cooder. The output was varied. Between the grooves, you can hear the beginnings of a tear in the generation gap. Hazlewood is relaxed with the straight-up country of old buddy Sanford Clark (see the fine “Black Widow Spider” – a future hit for Richard Hawley, perhaps). The baroque pop of “Sunshine Soldier” by Arthur is simply extraordinary. But Hazlewood’s instincts pushed the Detroit girl group Honey Ltd away from political engagement. Indeed, LHI’s trademark is the tension between Hazlewood’s instincts and those of his acts (see the tethered psychedelia of “Maharishi”, by The Aggregation). Other acts were invented to fill quotas (Rabbitt, with Hokom’s pet rabbit Friday on the album cover). Of course, the whole thing is overshadowed by Hazlewood’s own recordings. True, Ann Margret isn’t quite a replacement for Nancy Sinatra, because the Swedish starlet over-enunciates. But the duets with Hokom are among his best work. The Virgil Warner and Suzi Hokom album is equally good – see the sultry “Summer Wine”. LHI ends when Hazlewood moves to Sweden, to collaborate with Torbjorn Axelman, escape the taxman, and help his son avoid the draft. The move coincides with the end of his relationship to Hokom, which he chronicles in the extraordinary 1971 album Requiem For An Almost Lady (included in full). It’s a nasty, poetic, beautiful, hurting record, in which the wounded poet tries to understand the hangover of his own hurt. As usual, Lee Hazlewood is the hero of his own song, making fun of the pain, looking for revenge in the comedy of his pathos. “In the beginning, there was nothing” he croons, “but it was kinda fun to watch nothing grow.” Alastair McKay EXTRAS: 10/10 The box comes in two editions. The simpler version has 4 CDs, with 107 tracks (all Hazlewood’s LHI Recordings, plus key tracks from LHI stable), 172 page book, Cowboy in Sweden on DVD (odd, but worth it), flexidisc and other ephemera. Deluxe edition also has 3 DVD data discs, including 17 albums, and 140 single A&B sides in WAV and MP3 format. Plus promo photos. Q&A SUZI JANE HOKOM How did you meet Lee? We all hung out those days at Martoni’s, an Italian restaurant in the heart of Hollywood where everybody hung out – promotion men, A&R guys, artists. I was 19, I’d already made some records, and I met him through mutual friends. I found him so refreshingly fascinating. How was LHI run? All of us were in it for our lives. We were there ’cause this was going to be our shot at doing something fabulous. But then you have The Master dictating what he thinks, and Lee wasn’t the hippest when it came to rock’n’roll. With the little finite nuances of these artists – sometimes he didn’t get it. How would you sum Lee up? Basically, Lee really was a writer. I would have loved to have seen him write books. He just had such an interesting take. There was a bitterness, and yet a great sensitivity and romanticism. That’s what I fell in love with – his writing. I think writing was a way that he could express what he couldn’t express himself in life. He was a small guy. Short, tiny. There was this gruff exterior … he called himself Grey Headed Old Son of a Bitch – every love letter was signed GHSOB. That was who he decided he was gonna be. His sensitivity and his great humour came out in his writing. INTERVIEW: ALASTAIR McKAY

Cosmic Cowboy’s indie label exhumed…

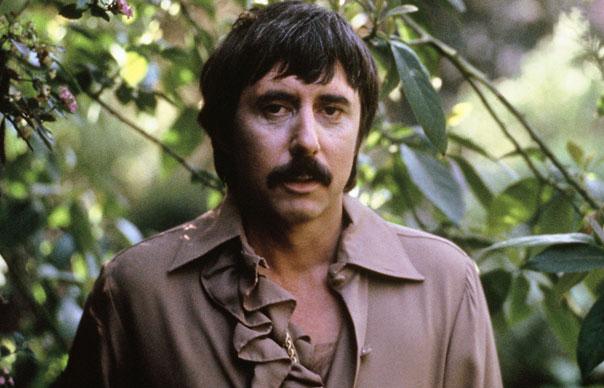

Six years after his death, 47 years since his biggest hit (Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made For Walking”), Lee Hazlewood remains an enigma. Partly, he designed it that way. Throughout his career, he cast himself as an outsider, a drifter, a cowboy. What he didn’t quite accept, though the evidence is plentiful, is that in career terms he had a habit of shooting himself in the high-heeled boot.

The label, LHI, was formed in 1966 when Hazlewood’s reputation was rising. Prior to his unlikely star-turn with Sinatra, the former DJ from Oklahoma had been round the block a couple of times; scoring a hit with Sanford Clark in 1956, and adding the echo to Duane Eddy’s twang. He had also laid the foundations of an idiosyncratic solo career with Trouble Is A Lonesome Town (1963) and The NSVIPs (1964).

LHI took his ambition to another level, though it remains unclear just what Hazlewood wanted from the imprint. It can be viewed as one of the first great indie labels, though it was run from an office at 9000 Sunset Blvd with scant regard for commerce. Indeed, Suzi Jane Hokom, whose roles included production and art direction (as well as being romantically involved with Hazlewood) suggests the boss wasn’t bothered about hits. He ran a label because others were prepared to fund it.

Still, he gave his co-conspirators free rein, and strange things happened, even if few people noticed. Hokom was allowed to develop as a producer, and used her influence to get the International Submarine Band signed, though Hazlewood was at best ambivalent about Gram Parsons. (Hokom suggests his disinterest was, at root, based on jealousy).

A relaxed, chaotic endeavour, LHI had an open door approach, and a studio band comprised of key members of The Wrecking Crew (guitarist Al Casey was an associate from Hazlewood’s time as a DJ in Phoenix), with back-up from the likes of future-Byrd Clarence White and Ry Cooder. The output was varied. Between the grooves, you can hear the beginnings of a tear in the generation gap. Hazlewood is relaxed with the straight-up country of old buddy Sanford Clark (see the fine “Black Widow Spider” – a future hit for Richard Hawley, perhaps). The baroque pop of “Sunshine Soldier” by Arthur is simply extraordinary. But Hazlewood’s instincts pushed the Detroit girl group Honey Ltd away from political engagement. Indeed, LHI’s trademark is the tension between Hazlewood’s instincts and those of his acts (see the tethered psychedelia of “Maharishi”, by The Aggregation). Other acts were invented to fill quotas (Rabbitt, with Hokom’s pet rabbit Friday on the album cover).

Of course, the whole thing is overshadowed by Hazlewood’s own recordings. True, Ann Margret isn’t quite a replacement for Nancy Sinatra, because the Swedish starlet over-enunciates. But the duets with Hokom are among his best work. The Virgil Warner and Suzi Hokom album is equally good – see the sultry “Summer Wine”.

LHI ends when Hazlewood moves to Sweden, to collaborate with Torbjorn Axelman, escape the taxman, and help his son avoid the draft. The move coincides with the end of his relationship to Hokom, which he chronicles in the extraordinary 1971 album Requiem For An Almost Lady (included in full). It’s a nasty, poetic, beautiful, hurting record, in which the wounded poet tries to understand the hangover of his own hurt. As usual, Lee Hazlewood is the hero of his own song, making fun of the pain, looking for revenge in the comedy of his pathos. “In the beginning, there was nothing” he croons, “but it was kinda fun to watch nothing grow.”

Alastair McKay

EXTRAS:

10/10

The box comes in two editions. The simpler version has 4 CDs, with 107 tracks (all Hazlewood’s LHI Recordings, plus key tracks from LHI stable), 172 page book, Cowboy in Sweden on DVD (odd, but worth it), flexidisc and other ephemera. Deluxe edition also has 3 DVD data discs, including 17 albums, and 140 single A&B sides in WAV and MP3 format. Plus promo photos.

Q&A

SUZI JANE HOKOM

How did you meet Lee?

We all hung out those days at Martoni’s, an Italian restaurant in the heart of Hollywood where everybody hung out – promotion men, A&R guys, artists. I was 19, I’d already made some records, and I met him through mutual friends. I found him so refreshingly fascinating.

How was LHI run?

All of us were in it for our lives. We were there ’cause this was going to be our shot at doing something fabulous. But then you have The Master dictating what he thinks, and Lee wasn’t the hippest when it came to rock’n’roll. With the little finite nuances of these artists – sometimes he didn’t get it.

How would you sum Lee up?

Basically, Lee really was a writer. I would have loved to have seen him write books. He just had such an interesting take. There was a bitterness, and yet a great sensitivity and romanticism. That’s what I fell in love with – his writing. I think writing was a way that he could express what he couldn’t express himself in life. He was a small guy. Short, tiny. There was this gruff exterior … he called himself Grey Headed Old Son of a Bitch – every love letter was signed GHSOB. That was who he decided he was gonna be. His sensitivity and his great humour came out in his writing.

INTERVIEW: ALASTAIR McKAY

The soundtrack will feature instrumental versions of 'Porno' and 'Supersymmetry'. Both tracks appeared on the Canadian band’s UK Number One album, 'Reflektor'. The latter was apparently written for the film, according to its director Spike Jonze.

In an interview with

The soundtrack will feature instrumental versions of 'Porno' and 'Supersymmetry'. Both tracks appeared on the Canadian band’s UK Number One album, 'Reflektor'. The latter was apparently written for the film, according to its director Spike Jonze.

In an interview with