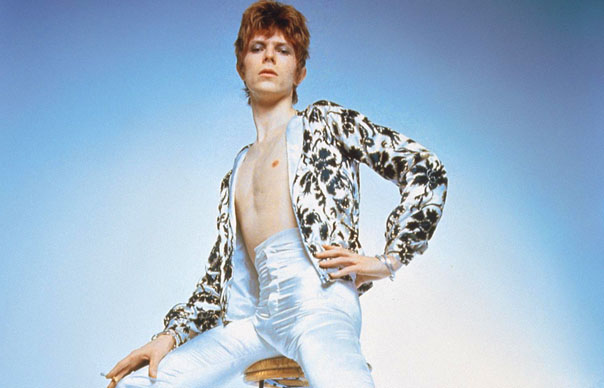

In this exclusive interview from Uncut’s October 1999 issue – run across four parts – David Bowie looks back on 30 years of genius, drugs and derangement. Words: Chris Roberts

_______________

David Bowie’s one of those people you travel to meet knowing that whatever agenda you have – perhaps to talk about his records, his images, his imaginings – he’ll unwittingly all but scupper it with a carpet-bombing charm offensive and voracious intellect. In the three times in the ’90s this writer has interviewed him prior to this meeting with Uncut, he’s zealously pontificated on Russian politics, the art of Johannesburg, chaos theory and the number of microchips in the average aeroplane. He’s done this while putting the journalist completely at ease with a matey approachability, yet revealing only tantalising fractions of “himself”. It takes resolve, and a temporary suffocation of the fan within, to bring him down to the level of talking about pop music, let alone who he is, who he once was, who he might still be.

When, in 1979, Valerie Singleton asked if the media’s tendency to view rock stars as a bit thick bothered him, he smiled and said, “Not at all. I’m very thick.” Which is just about the cleverest thing a rock star could ever say. He gets on well with Tony Blair now, and with prominent art historians; he jogs occasionally, and doesn’t drink. Two years ago, as the first big-league artist to float himself on the stock exchange – something of a move up, or towards the centre of things, from a tin can far above the world – he became debatably the richest British entertainer alive.

And yet this is the once coke-addled, gender-bending, demon-seeing, perhaps even Fascism-expounding paranoid egomaniac, who, after struggling determinedly for years, found global acclaim to be a royal screw-up, and perversely killed off each new persona just as it won love. This he repeated until he realised it was the sheddings, the acts of transformation, the rebirths, that were doing the winning. Until he realised that in pulling new identities out of himself he made us think we could pull new identities out of ourselves. Now a successful musician, actor, painter, sculptor and Internet guru, he can pursue whichever medium he pleases, as, with little to lose, the classic example of how to turn 50 and stay interesting. He is still revered by younger artists, his influence ubiquitous. Happily married, his self-esteem – rocky even throughout the years when “Bowie Is God” was graffitied on just about every suburban street wall – is settled and serene. He’s also manically busy and creative.

In the ’70s, Bowie co-opted shock value to become the most prominent and challenging of stars, then jettisoned it when everybody else caught up. He then introduced the glam generation to the joys of soul music, and forced the rock cognoscenti to concede that art wasn’t a dirty word. “There’s new wave, there’s old wave, and there’s David Bowie,” ran the slogan alongside one of the many zeitgeists he’s hurdled.

Bowie was the thinking person’s rock Messiah, an actor observing himself playing a role for which his parallel talents as a great singer and songwriter were uniquely suited, given his knack for the most agile appropriation and artifice. If he saw someone else doing something he liked, he’d do it better. If no-one else was doing it, he’d hold and hold and hold, then play his card at exactly the right moment to cause maximum subversion and sparkle. Although his more recent work has been as often merely eccentric as truly inspired, his charisma, as he cares less about it, grows. He plays it down, but you still know you’re meeting aristocracy.

All of which brings us to New York, on a fine August morning, at the Fifth Avenue offices of Virgin Records, at what’s the crack of dawn for me but probably halfway through the day for Bowie. The journalist is five minutes early; the artist is five minutes late. He’s doing things. He’s always doing things.

_______________

YOU’VE BEEN AROUND

Preparations for the legend’s arrival have been made. A dozen scented candles adorn the boardroom table and, more importantly, there’s a fresh pack of Marlboro Lights, a lighter, and an ashtray in every no-smoking room.

He glides in, long-haired in a heatwave, enthusiastically bearing a cassette. The hair throws you a little: how come this man never looks like his most recent photos? Tall, long-limbed, someone who strides, he’s wearing clothes which are so nondescript it’s remarkable; greyish-brown shirt and trousers.

“Hi”, he says, “Listen, can I just play you this?” He’s been remixing a track called “Seven” from his new album, hours…, and, like a kid in a new band, wants the nearest human being to hear it at once. On it goes, and I am placed in the only slightly surreal position of having to nod along approvingly to this world exclusive while steering clear of being a sycophantic twit. I like it. He likes it. “Lovely,” I go. “Yeah,” he grins.

Coffee is brought, and I check he’s aware that, as well as discussing the Bowie of ’99, we’re attempting – in our too brief allotted time – an overview, a retrospective look at his 30 years as a shape-shifting icon. Here’s what our most articulate, durable rock god says.

“Oh, fuck, shit. No, I didn’t know that. Ha, good luck! All right, I’ll try. OK.”

Thirty years as a superstar, I go, making it sound attractive. Bearing in mind that his 17 studio albums from 1969 to 1989 are re-released (again) this month. Thirty years as Major Tom, Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane, Cracked Actor, Thin White Duke, Beep-beep Pierrot, mainstream crooner, bloke from Tin Machine, earthling, Cyber-seer, multi-millionaire . . .

“Thirty years as an occasional front cover,” he muses. “Heh heh. Well, this gives me the opportunity to now go out and get a spoon.”

A spoon?

“A spoon,” he says, furrowing his brow, “might affect my performance.”

David Bowie, one of the first rock stars to enter cyberspace with a vengeance, has learned to temper his obsession with the internet. He only plays with it at night now, or “the wife is out the door – zoom!” He has to be careful. She’ll say, “Are you ever coming to bed?” “Hold on just a minute,” he’ll plead. “Come and have a look at this, you won’t believe…” “No, I am not coming to have a look,” she’ll reply. “I’ll see it tomorrow. All right?” “But,” he’ll say, “it’s really incredible.” “I’m sure it’s incredible, darling,” she’ll sigh, “but please come to bed now.”

So what he does is he gets up at five AM and checks out his sites, makes sure everything’s up to scratch, till around nine or ten.

“There’s nobody about. Well, Iman’s about, but I mean in the outside world there’s nobody about.”

He hasn’t let it distract him from music too much. “I’m aware where the drugs are these days. I see ’em coming! They’re not all chemicals, y’know. I look at the screen, and think: this is a drug. I’ve gotta be careful with this, because I can get hooked ever so easily.” Through most of the ’70s, he admits, he was “cracked-up and broken… not on this planet”.

I ask what surprises him most about the way he’s perceived today, and he answers, “I guess I am what the greatest number of people think I am. And I have no control over that at all. This lot on Bowienet are quite funny and sarcastic – they’re not, like, goths, all serious and heavy. They do a lot of sending-up, which I like.”

They’re cheeky as much as reverential?

“Absolutely, yes. So there’s an awful lot of referencing ‘Laughing Gnome’ and Dame Bowie and all that.”

Which you’re OK with?

“Oh, God yeah! I had to get over that a long time ago.” He laughs the laugh of the happy. “But then as we all know, history is all revisionism. One makes one’s own history.”

_______________

HIS NAME WAS ALWAYS BUDDY, AND HE’D SHRUG . . .

It’s tough chaining Bowie to one subject at the best of times: he’s too interesting and interested. “I do this now,” he mentions, the second the tape recorder’s on. “So I know about the fears and horrors of not having enough batteries, the embarrassment of getting it to work in front of them.”

He’s been for some years conducting interviews for the publication, Modern Painters, beginning with former neighbour and fellow Swiss tax exile Balthus, moving through Lichtenstein to Hirst and Emin.

“I’ve done a lot, and I love it,” he says. “For me it’s far preferable being on that end of it. I’m interested in how artists work. The process. How they got where they got, why they’re like they are, how they do what they do. Those three things are what you want to find out about a person you admire. The most delightful experience recently was Jeff Koons, who I adored. He’s so ultimately American, a dream. Very sweet, simplistic, almost a naïve presence. Terrific company. I’ve not done anyone yet that I don’t admire, but I’ve got a couple coming up, and that’s gonna be odd. I suppose I ask the same questions, but how do I greet the answers? Should I get personal or remain objective? Is there room for editorial comment? What do I do if he’s a prick? An unctuous, obsequious prat?”

Pretend you’re a character in a play?

“But… it’s all theatre, y’know. Everything. I mean, even Springsteen’s theatre. Whether they like it or not. It’s a performance, an interpretation of something. That’s what it is. That’s what we do.”

Manhattan sirens blare through the window and Bowie half-turns his head for a second. When he turns back, the eyes do that thing, the David Bowie thing. Right, you think, that’s him.

“All we dysfunctional people who feel that it’s important for more than three people to know our opinion, that’s why we’re in this ‘music biz’. All the painters, all the anything else – it’s where all the nutcases go when they haven’t been locked up. They go into the arts. Because nobody in their right mind needs to tell hundreds or thousands of people what it is that they believe.”

Oh, it’s in everybody to some degree, that can-I-get-a-witness thing…

“Is it? Oh. So I’m one of the sane ones, you’re saying?”

David Bowie, who has studied and feared the topic of mental illness all his life, and whose estranged half-brother Terry committed suicide in 1985 (hence “Jump They Say” from 1993’s Black Tie White Noise, the first song he’d written about him since “The Bewlay Brothers”), finished mastering his new album yesterday. Simultaneously, he and collaborator Reeves Gabrels started writing some new tracks. This morning, he’s already chatted with Pete Townshend (“we see far too little of each other, he’s a lovely man”), with whom he bemoaned the fact that constant travelling, currently between New York and London in his case, means he keeps missing people. “It’s a shame: I’ve got to stop befriending nomads.”

You could keep still yourself for a few days.

“Yes,” he agrees, adopting mock Dame David accent. “Let them come to one.”

You’re relentlessly prolific.

“I know. Apart from one short time, I’ve never really suffered from blocks.”

This one short time was probably the crisis of confidence and direction after Let’s Dance and its tugboat sequels – Tonight (1984) and Never Let Me Down (1987) – rattled his cutting-edge credibility for the first time in nearly two decades. “I never try and analyse why that is, because it might cause me to have one. It freely flows out. Whether it’s writing, making music, or painting, I don’t have a problem that way. There’s always something happening. Probably because what others might have as time off, as relaxing time, I apply to working… I can’t be without doing something. I don’t take kindly to holidays; they’re forced sabbaticals.”

Indeed, Bowie’s work rate – for an alleged poseur – has always been the stuff of myth. Even at the height of his drug-induced crying jags and hallucinations and self-imposed isolation, he would pull 48-hour non-stop stints in the studio.

Does he feel a sense of guilt if he stops?

“Not guilty so much as irritable. I sit there stubbornly waiting for the sun to go down, mumbling, ‘Have you had enough of your holiday now? Can we go back and get on with things?’ My compromise is, if I’m not working, I’ll be inquisitive. I’ll make sure we go somewhere interesting, so that I can scavenge about and see if there’s anything I can take away with me that’ll become part of what I do. I guess I’m always looking for experience or titillation of some kind. I’m never still. I’m an itchy-crawly kind of guy. That’s why I like New York so much: there’s always something going on. I once asked David Byrne why he’d chosen to live here, and he said, ‘Um, because you look out of the window and someone falls down.’ Perfect.”

Before we blast through the past (and touch on such pop-trivia subjects as absolute truth, personal belief systems, self-abuse and, er, Sir Thomas More), we need to set Bowie’s new opus, hours… , in context. Outside (1995) found him back in touch with Brian Eno and getting in touch with his darkside again, tapping into the now over-familiar themes of pre-millennial angst and serial killer aggrandisation. Earthling (1997), a healthily ironic title, was a patchy drum’n’-bass experiment with what were probably then referred to as “the latest sounds”.

Yet hours… is Bowie in that rarest of guises: man singing songs, acknowledging bona fide emotions. (Contrary to lore, this is something he has done before: think “Be My Wife” from Low or “Can You Hear Me?” from Young Americans. Contenders such as Ziggy’s “Rock’n’Roll Suicide” were more distanced, considered . . .).

“It’s a more personal piece”, he says of his 20th solo studio album proper in 30 years, “but I hesitate to say it’s autobiographical. In a way, it self-evidently isn’t. I also hate to say it’s a ‘character’, so I have to be careful here. It is fiction. And the progenitor of this piece is obviously a man who is fairly disillusioned. He’s not a happy man. Whereas I am an incredibly happy man! So what I was trying to do, more than anything else, was capture some of the angst and feelings of… guys of my age. I’d say, broadly, it’s songs for my generation. People who’ve lived through the late ’60s, ’70s, and part of the ’80s… although the ’80s don’t really come into this album. It’s a long reach back, generally. I was trying to capture elements of how, often, one feels at this age.

“So it’s personal, but not some hybrid fantasy. There’s not much concept behind it. It’s really a bunch of songs, but I guess the one through-line is that they deal with a man looking back over his life.”

_______________

LIFE JUST KISSED YOU HELLO

This man, this narrator, definitely isn’t you?

“No, no – because there’s one song where I’m talking about how we’ve got to break this relationship up, y’know – and please don’t read things into that! My wife and I are extremely happy; I’d like to state quite publicly – haw, haw. But there was a time in my life where I was desperately in love with a girl – and I met her, as it happens, quite a number of years later. And boy, was the flame dead! So in this case on the album the guy’s thinking about a girl he knew many years ago, and she was ‘the great mistake he never made’. See, I know how that feels, but it’s not part of my current situation. I’m much too jolly. I’m inwardly jolly.”

So this isn’t you probing your heart and soul?

“God, right, let it pour out – aaargghh! No, not at all.” (I notice the straight teeth, not the fangs of photographic legend, which he resisted getting fixed for decades. He only gave in when they started giving him real pain.) “But it doesn’t mean I don’t take it seriously. I have friends who are in similar situations; I draw from people I know. I see what they’re going through, and think, God, if I could help them… but you can’t ever help somebody sort out their internal life. Never. Even if you know what’s wrong, you can’t tell ’em. You can give support, but they’ve got to do it themselves.”

Bowie, notoriously, married Angie Barnett in 1970. By their divorce 10 years later they were barely on speaking terms, and Bowie won custody of son Joe (aka: Duncan Zowie Bowie). Early on, however, many reckon Angie’s commitment to her husband’s lust for fame was admirable, and she was an essential motivator, contributing ideas to the crucial Ziggy look and presentation. Her bitch’n’tell book, Backstage Passes, is a self-serving, one-sided rant, fuelled by loathing for Corinne “Coco” Schwab, who replaced her as Bowie’s confidante and buffer from management hassles, but if even a 20th of it is true, Bowie’s bisexuality back then was no pose. It got every mixed-up teenager’s mother in a whirl.

Prior to the pugnacious Angie, Bowie had a long romance with a ballerina, Hermione Farthingale, the subject of “Letter To Hermione” from Space Oddity. His sexual appetites, while by no means latent before stardom, ballooned post-fame. “Not too many gay gods,” Marc Bolan once chuckled, “have slept with 5,000 chicks.” Later affairs included the Berlin transsexual, Romy Haag. A leaning towards black girls then seemed to usurp bisexuality. In the Eighties there was a serious, three-year relationship with Melissa Hurley, a dancer from the Glass Spider tour.

In 1990 he met Iman, and “started naming the babies on the first night”. He proposed on one knee on a boat cruising down the Seine in Paris on the first anniversary of their meeting. He agreed to an AIDS test and swore off all drugs. They married in 1992 in Lausanne. And again in Florence.

A recurring theme of the album seems to be: no regrets.

“Yes, that is from me. I don’t have regrets. If I am cajoled into looking at the past, which I do very infrequently, I tend to look on it as not so much luggage as… wings. My past has given me such a fantastic life. A lot of it negative, a lot positive. For me it’s been an incredible learning process, arriving now at a situation where I… know far far less than I knew when I started out!

“There again, nobody knows more than a young person knows. I knew so much when I was about 25. I had an answer for everything, knew all the answers…”

_______________

FUTURE LEGEND

Even before reaching that ripe old age, David Robert Jones, born in Brixton in 1947, had asked a few questions. Quickly shuffling off the mortal trappings of a fractious, working-class family, his early mods’n’sods bands included The King Bees, The Manish Boys and The Lower Third.

Changing his name to avoid confusion with The Monkees’ singer, he released a loopy, self-titled 1967 album and numerous flop singles, riddled with music hall structures and Anthony Newley vocal mannerisms, while dabbling in folk, mime, acting, dance, Buddhism and the obligatory bohemian lifestyle.

In 1969, he finally forged a hit with “Space Oddity”, inspired by Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey and helped by the Apollo moon landing broadcast. The sister album was the work of a trippy hippie, but the chameleon was just waking up, unfurling the flag.

People sometimes forget just how many records the little bombardier made before hitting big fame…

“And unfortunately they were all released! I mean, I must’ve had 743 singles come out before ‘Space Oddity’. And half of them daft as a brush. And the other half – well, there may have been potential, but only so much. Ha!

“But it’s kinda fun now, actually – I see sites on the Internet where they study those areas very intimately. You can see them picking through the peppercorns of my manure pile. Looking for something that might indicate I had a future. They’re few and far between, but they have come up with some nuggets.”

“So yes, the whole of my learning period is all out there, all released. It took me an awful long time to work out what it was that I did. I guess what made it so difficult was that I was never in love with one kind of music and one kind of music only. At that point, particularly, it wasn’t ‘right’ to have an interest in all areas. It was make-your-mind-up time. You were either a folk singer or a rock singer or a blues guitarist… you were a thing, and you could definitely say that’s what you were. Now, that kind of singular craft seems almost quaint. This TV show came on the other day and it was, like, Mountain, Fleetwood Mac, Joe Walsh… and I thought, God, that approach to music seems so incredibly out of step now. And I think I felt that back then! I felt: well, I don’t wanna be like this. I wanna keep my options open; there’s lots of things I like. So it was: ‘How can I do this so I can try everything? How can I be really greedy?’”

David Bowie: “I’m hungry for reality!” – Part 2

David Bowie: “I’m hungry for reality!” – Part 3

David Bowie: “I’m hungry for reality!” – Part 4