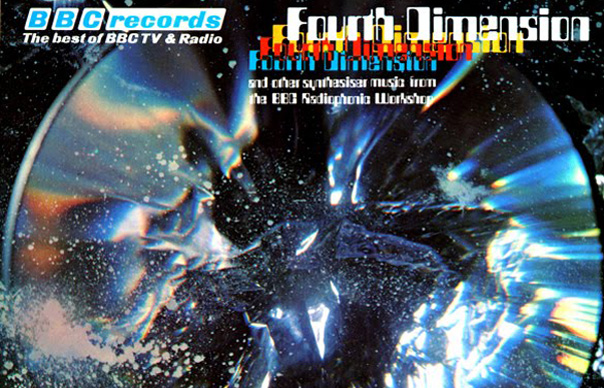

One of the things I wrote about in the new issue of Uncut is a review of the latest vinyl reissues from what was the BBC Radiophonic Workshop. For a panel to accompany the review, I had the good fortune to speak to composer Paddy Kingsland, one of the legendary studio boffins currently touring in the live iteration of the Workshop.

Kingsland was among the Workshop’s early Seventies’ intake, whose arrival coincided with the advent of the synthesiser. I suspect some still mourn the passing of the Sixties’ era of ramshackle ingenuity, where arcane practises of splicing tape with razor blades were replaced by the keyboard. But arguably Kingsland’s work on shows like The Changes, The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy and Doctor Who – in particular, his keyboard fanfares that soundtracked the 1980/81 season – had as much impact on a new generation of television viewers as the work done by his illustrious predecessors.

Anyway, Paddy was terrific – warm, engaged, and full of memories of his time at the Workshop, as well as his more recent experiences since the Workshop reconvened as a live entity in 2009. Inevitably, I couldn’t fit everything into the magazine, so I thought I’d run the transcript in its entirety here. It’s 2,600 words. I hope you enjoy it.

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner.

__________

What was your background prior to joining the workshop?

I started off playing in bands at school and just before that I was interested in fiddling around with old radio sets and making up amplifiers and all that sort of stuff, and that led to an interest in guitar amplifiers. And then I started playing in bands around the year of The Shadows and that sort of thing.

Early British rock and roll….

Yeah. In fact, American, because I soon progressed onto Chuck Berry and all that business. My brother was about five years older than me and he bought new records every week and had all the Elvis ones and Fats Dominos ones and that era of stuff. That was my starting point. I didn’t go to university and I joined the BBC as a technician around about 1966.

What was your first experience of the Workshop?

I had to go on one of these training courses to broaden your experience of the technical side of things in the BBC and production. One of the things we did was a visit to the Radiophonic Workshop. There was a talk by Desmond Briscoe [co-founder of the Workshop] in what was called the piano room. We all sat down and he gave this talk and somebody played us the tape of example sounds that Desmond had prepared. He liked to show off the Workshop. Then we had a little tour round the place, had tea, and then Desmond said, “Well if anyone is really interested in all of this, perhaps they’d like to come along for a week and explore things in a bit more depth.” So I did, and never looked back from there.

What kind of people were Desmond Briscoe and Delia Derbyshire?

Desmond was originally a studio manager. He was very into drama and very curious about all kinds of things. He didn’t have a university education or anything like that, so he didn’t come with a degree in music – unlike Delia, who did. She went through the system in the conventional way but she was very talented. Desmond was very interested in the idea of making sounds. He was a showman, really. He liked to make an impact on an audience. He was always after making the best effects out of whatever it was he was doing, whether he was making the sound effects for something like Quatermass, or putting together, as he did in later life, complete programmes. He was very proud of that, really. It rewarded his remarkable attention to detail and devotion to making something that was really special sort of production.

What was the perception of the Workshop within the BBC?

There was a huge range of opinions. There were a lot of producers who had no budget, particularly in Schools Broadcasting. The difference between radio and television budgets was huge, so for a lot of radio people the idea of hiring in musicians to come and do something would be completely out of the question, whereas the Workshop was a much more attractive alternative. There were lots of people who liked the idea that they could do extensive sound work to go into their production, which would give the impression of hugely better production values – like a Schools Production about science for instance. But there were a lot of people who were skeptical. I think most people had a very hazy idea of what it was that the Radiophonic Workshop did. They certainly admired things like Quatermass and a lot of the theme tunes that were used in the World Service and programmes like Tomorrow’s World.

You arrival at the Workshop coincided with the advent of the synthesiser. My understanding is that previously, work had been quite labour intensive – cutting tape and such. Whereas the synthesizer allowed you to create something quite quickly. Is that true?

That’s absolutely what happened. Particularly when you had keyboards on synthesisers – because some of the early ones didn’t have a keyboard and were simply another way of generating electronic tones with the latest controls added to it. But when they added keyboards on, you could just play a tune – whereas John Baker would spend a day cutting tape together to make that type of sound. It’s a bit like the days when you had film on a reels that went through a machine and when you would go through editing a programme it took 10 minutes to wind the film back when you reached the end. In this way, they talked about the edit and what they were doing. There was time to think about the process. Synthesisers made it easier, but they made it less painstaking.

How did the arrival of the synthesiser change the remit of the Workshop?

A lot of the special sound was done on synthesizers. But the early stuff that Brian [Hodgson] did, was all done with the usual array of oscillators, plucked strings and that sort of thing. It had a more organic feel to it. I only did one of those special sound things for Doctor Who, for a story called The Sun Makers. I can remember consciously thinking about that at the time and wanting to make the sounds more organic, if that’s the right word, made out of real things, rather than just drones and hums, which could be made on a synthesiser fairly quickly. Another thing, if you’ve a synthesiser droning and humming while you’re trying to play a tune it doesn’t bloody work together sometimes. The synthesisers were a great labour saving device but when they first came in, they were kind of research tools, in a way. You had to plug everything up and make the sounds yourself. But, later, presets made sounds for you and all you had to do was push the button and you got the sound. That was unfortunate because everybody started sounding the same. I don’t mean at the Workshop necessarily, I mean generally speaking. People were buying synthesisers at home and using them at schools.

What were your early commissions for the Workshop?

I think for the first one electronic bagpipes were required. It was for Radio Scotland. They wanted a little tune played and I did it on a VCS3. Afterwards I did a few things using the tape techniques. That was one of the first things. I did some stuff for Scene And Heard because I worked on the programme as a studio manager. And then all sorts of things followed. Take Another Look was a nice thing to do. When they first invented more advanced lighting for film and infrared, they were able to film things close up and in great detail. Take Another Look was a programme that looked at everyday things in a different way. I did some music for that.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dqC4juER6VA

The Changes is a landmark soundtrack for you. I know the BFI are releasing it on DVD in the Autumn, but am I right in thinking that the soundtrack is still unavailable?

There was a little EP done of it. I’m doing a version of new of bits from it that I want to put together, a remake if you like.

A director’s cut?

No, just a few of the themes put together in a similar way to how they were done on the [original] EP. Apart from that, no, nothing’s escaped or been released of that. It was good that – I don’t mean my music particularly – but the whole thing. It was a lovely idea. Peter Dickinson seemed to be quite ahead of his game when he wrote about how the machines were going to destroy the world and everybody rise up against them.

The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy – on radio and TV – was another major work for you. Where did you involvement in that start?

The very first episode was produced by Simon Brett. At that time, he a producer in the Light Entertainment and Comedy Department of BBC Radio. Simon was more used to going to a studio, he’d have a guy playing in taped effects, someone else doing spot effects like telephones, doors, cups and saucers, then a bunch of actors – he wouldn’t really do that much to it. But he saw the possibilities of what we were doing. Then he got this script for the first episode of Hitchhikers by Douglas Adams and he thought what we were doing would lend itself to that. In fact, Episode 1 has very little to do with science fiction compared to the rest of it. It takes place on Earth and the first effect is a bulldozer! There are a few little things in there. We did the code for the book, The Guide. Its all little real sounds cut together with a little bit of synthesiser sound cut in. The end of the world – just a little effect there! And then the Vogon space ship – not much Radiophonics in it. But we put it together and he came over with Douglas, having put it down with the actors on 8-track I think. I had made the effects up in advance and we mixed it and then put that episode together. That was the beginning of that. But I didn’t do the rest of that first series because I was away doing a programme for Radio 3 at the time for I Continuing Education. I came back and saw that it had been an absolutely huge hit! Then I was asked to come back and do a Christmas Special later that year, then the next radio series, which was just great fun to do.

You were involved in Tom Baker’s last season on Doctor Who and Peter Davison’s first season. What do you remember of working on that show?

I worked on it, so did Peter Howell, and I think Roger Limb. We went to a place in Shepherd’s Bush, I should think it was next door to the television theatre, where they housed a few people from drama series. They had put everything together and edited it but they hadn’t done any sound post-production on it. They had made a copy of it onto some early cassette video machine – this was before VHS became standard – and I had a time code copy. I’d watch it with the director who would brief you on what he wanted. Occasionally, you would think of something and come up with suggestions. But generally – and in particular people like Peter Moffat who is wonderful – they would have a clear vision. Occasionally, there’d be a ‘painting over the cracks’ bit where we would do a small section of music to cover up something that had gone wrong during the recording! You would walk away with a list of 10-12 cues with time codes marked and a list of adjectives, feelings or themes that the director had mentioned when he was talking. Then you had a week to make the music. Now that wasn’t a huge amount of time if you had to play all the parts yourself on a synthesiser or make it all. So that’s the way it worked and frankly I made it up as I went along. Not because – that sounds slapdash, doesn’t it? – I had just found out that is the best way of doing this. And statistically that gets more ‘hits’ than mucking about for weeks on end.

How did the Workshop come back together?

It was about 20 years ago. A lot of it has to do with Mark Ayres and Peter Howell. We all met because when the BBC closed the Workshop down. There were a lot of tapes, a library of old things, that I thought ought to be kept. Mark took on the job of looking through the tapes. That grew into a bit of support from the BBC and a very small budget for actually keeping the thing alive, the actual tape library. It was largely a labour of love for Mark, it took him weeks, he catalogued it all and essentially built an archive. That’s somewhere in the BBC now.

When did you guys start talking about playing together?

There was an event at the Roundhouse in 2008. I wasn’t involved in it. But from that grew the idea of doing a concert with the people who were there who could be assembled. Mark Ayres and Peter Howell discussed this with the Roundhouse and eventually in May 2009 we did a concert there. It was the most terrifying experience. We’ve all done live gigs but we’ve not that sort of thing. They approached me and Roger Limb and, I think, Dick Mills. I didn’t sleep the entire night after I said yes! I phoned up the next day and said, “If this is what it’s going to be like this the next two or three months I’ll have to say no because I think this is just so worrying doing this stuff live.” But once we got into playing together and rehearsing, it was great fun. We also had some fantastic session players to help us out. Gary Kettel, my old friend from years back who’s a great percussionist. Also Ralph Salmins, who’s a brilliant drummer. That was the beginning of it.

What’s it like on tour with the Workshop?

[Laughs] It’s like sitting in a train for five hours. It’s good fun chatting. The thing is, we all used to meet up in the canteen over lunch but apart from that we weren’t involve in each others’ productions very much or anything like that. At the Workshop everybody worked separately in separate rooms. And then lunchtime in the canteen there would be chatting, so it’s a bit like that dynamic all over again. The same old stories, remembering old bits and pieces, it’s quite fun really. And actually, I can’t speak for the others of course, but I think I wasted a lot of time really when I was there not being more friendly with people at the time. But I suppose we were just getting on with it. It was a job first and foremost.

You’re playing Glastonbury…

I can’t believe that. I hope it’s going to be alright. I have been totally surprised by it. And people have such affection for the Workshop – I don’t think it’s necessarily for the people there – us – it’s for the whole thing. Delia, and everyone who isn’t there. They kind of remember it and remember the impact it had on them when they were quite young, and I think that’s probably it. Then again we’ve done some new things and a lot of young people have gone for it as well. You see it. It’s a laugh – a bunch of old blokes going on stage and doing something that’s quite, you know, close to contemporary.

It’s extraordinary in some respects. I saw you playing in Shoreditch last year. It’s striking how some of the material, like Delia’s “Ziwzih Ziwzih OO-OO-OO”, still feels very current.

That is a good example. I arranged some extra bits to go on, which gives it some drive and punch, like when the drums come in. It was easy to do that because it was all there in the first place, but with a few bits of discord added. She had done all the work in a way. You know, she felt that Ron Grainer when he wrote the theme tune on the back of an envelope for Doctor Who, that he had done a lot of the work when she made it. But of course she really did make that into something very special. Something that few musicians at that time in a TV sound studio would have come close to. It wouldn’t have had that same impact. It still is a great idea. And that’s the interesting thing about what we’re doing now, it’s not just one person doing it, which it always was really, it’s a collection of people.

Paddy Kingsland’s Fourth Dimension and Peter Howell’s Through A Glass Darkly are reissued by on Music On Vinyl on June 2