Nuts week. A lot to recommend and check out here, including plenty of Youtube and Soundcloud links. Among the auspicious comebacks, one that’s slightly obscured is Cavern Of Anti-Matter, who feature Tim Gane and his old bandmate from the first Stereolab lineup, Joe Dilworth. The Purling Hiss and White Denim trailers look predictably tantalising; will report back when I’ve managed to grab the albums. Meanwhile, the Omar Souleyman (produced by Four Tet) and William Onyeabor (a bit of a cratedigger holy grail, this one) albums are mighty addictive; Jonathan Wilson has basically – and rather nobly - attempted to recreate “Pacific Ocean Blue”; “Crimson/Red” is the first Paddy McAloon album I’ve enjoyed since “Jordan: The Comeback”; Wooden Shjips still sound pretty much the same as ever, no matter how much their press releases hilariously try to differentiate from one album to another; “Another Self Portrait” is so much richer than many of us might have expected; and, yeah, Bill Callahan In Dub is quite the thing. Dig in… Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey 1 Bob Dylan – Another Self Portrait (1969-1971): The Bootleg Series Vol. 10 (Columbia) 2 Mark Kozelek & Desertshore - Mark Kozelek & Desertshore (Caldo Verde)… Review here 3 Wooden Shjips – Back To Land (Thrill Jockey) 4 Desert Heat – Cat Mask At Huggie Temple (MIE Music) 5 Prefab Sprout – Crimson/Red (Icebreaker) 6 Juana Molina – Wed 21 (Crammed Discs) 7 Lee Ranaldo & The Dust – Revolution Blues (Live At Maxwells) 8 Mandolin Orange – This Side Of Jordan (Yeproc) 9 William Onyeabor – World Psychedelic Classics 5: Who Is William Onyeabor? (Luaka Bop) 10 PJ Harvey – Shaker Aamer (Island) 11 Omar Souleyman – Wenu Wenu (Ribbon) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hqg702HcnBs 12 Ronnie Lane With Slim Chance – Anymore For Anymore (GM) 13 The Next Uncut Free CD 14 Bill Callahan – Expanding Dub (Drag City) 15 Jenks Miller – Spirit Signal (Northern Spy) 16 17 Various Artists – Live At Caffè Lena: Music From America's Legendary Coffeehouse, 1967-2013 (Tompkins Square) 18 19 Purling Hiss – Paisley Montage Promo (Richie Records) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uZUzHMIt4ts 20 Jonathan Wilson – Fanfare (Bella Union) 21 Bill Callahan – Dream River (Drag City) 22 Midlake – Antiphon (Bella Union) 23 Cavern Of Anti-Matter – Blood-Drums (Grautag) 24 White Denim – Corsicana Lemonade (Trailer) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YOcWeg5PgWo 25 White Denim – Pretty Green (Downtown) 26 The Julie Ruin – Ha Ha Ha (TJR Records) 27 Various Artists - Theo Parrish's Black Jazz Signature: Black Jazz Records 1971-1976 (Snow Dog)

Nuts week. A lot to recommend and check out here, including plenty of Youtube and Soundcloud links. Among the auspicious comebacks, one that’s slightly obscured is Cavern Of Anti-Matter, who feature Tim Gane and his old bandmate from the first Stereolab lineup, Joe Dilworth.

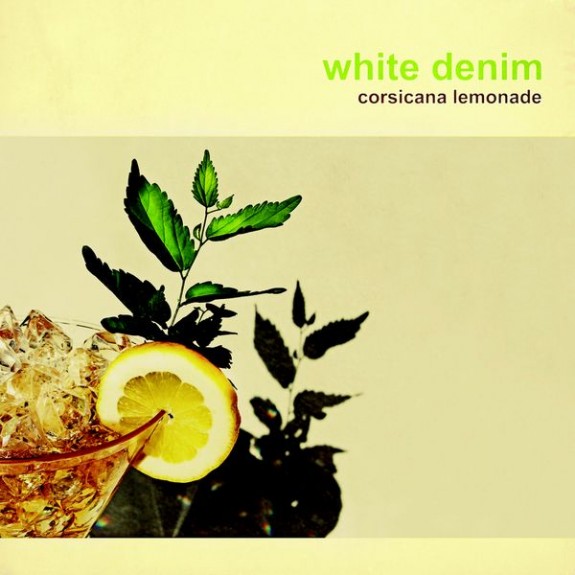

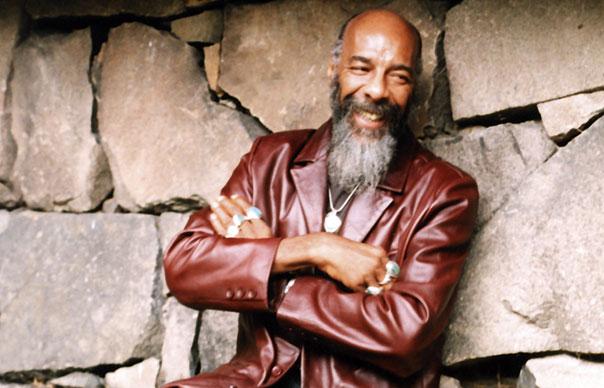

The Purling Hiss and White Denim trailers look predictably tantalising; will report back when I’ve managed to grab the albums. Meanwhile, the Omar Souleyman (produced by Four Tet) and William Onyeabor (a bit of a cratedigger holy grail, this one) albums are mighty addictive; Jonathan Wilson has basically – and rather nobly – attempted to recreate “Pacific Ocean Blue”; “Crimson/Red” is the first Paddy McAloon album I’ve enjoyed since “Jordan: The Comeback”; Wooden Shjips still sound pretty much the same as ever, no matter how much their press releases hilariously try to differentiate from one album to another; “Another Self Portrait” is so much richer than many of us might have expected; and, yeah, Bill Callahan In Dub is quite the thing. Dig in…

Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey

1 Bob Dylan – Another Self Portrait (1969-1971): The Bootleg Series Vol. 10 (Columbia)

2 Mark Kozelek & Desertshore – Mark Kozelek & Desertshore (Caldo Verde)… Review here

3 Wooden Shjips – Back To Land (Thrill Jockey)

4 Desert Heat – Cat Mask At Huggie Temple (MIE Music)

5 Prefab Sprout – Crimson/Red (Icebreaker)

6 Juana Molina – Wed 21 (Crammed Discs)

7 Lee Ranaldo & The Dust – Revolution Blues (Live At Maxwells)

8 Mandolin Orange – This Side Of Jordan (Yeproc)

9 William Onyeabor – World Psychedelic Classics 5: Who Is William Onyeabor? (Luaka Bop)

10 PJ Harvey – Shaker Aamer (Island)

11 Omar Souleyman – Wenu Wenu (Ribbon)

12 Ronnie Lane With Slim Chance – Anymore For Anymore (GM)

13 The Next Uncut Free CD

14 Bill Callahan – Expanding Dub (Drag City)

15 Jenks Miller – Spirit Signal (Northern Spy)

16

17 Various Artists – Live At Caffè Lena: Music From America’s Legendary Coffeehouse, 1967-2013 (Tompkins Square)

18

19 Purling Hiss – Paisley Montage Promo (Richie Records)

20 Jonathan Wilson – Fanfare (Bella Union)

21 Bill Callahan – Dream River (Drag City)

22 Midlake – Antiphon (Bella Union)

23 Cavern Of Anti-Matter – Blood-Drums (Grautag)

24 White Denim – Corsicana Lemonade (Trailer)

25 White Denim – Pretty Green (Downtown)

26 The Julie Ruin – Ha Ha Ha (TJR Records)

27 Various Artists – Theo Parrish’s Black Jazz Signature: Black Jazz Records 1971-1976 (Snow Dog)