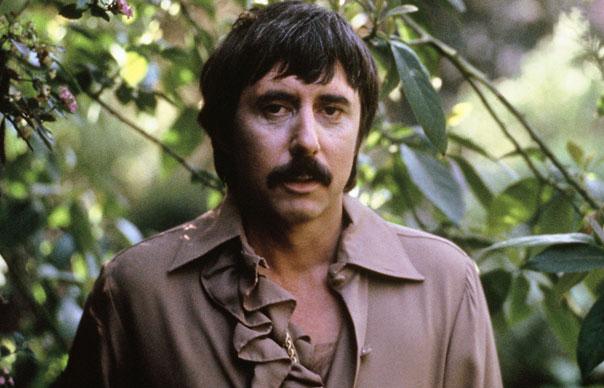

I interviewed T Bone Burnett as part of a piece on Inside Llewyn Davis, the new Coen Brothers film, which ran in the issue of Uncut on sale in December. What was originally meant to be a brisk 10 minute chat about working with the Coens and the film’s soundtrack evolved into a much longer conversation, the bulk of which, inevitably, I couldn’t work into the feature. So I thought I’d post it here for anyone interested in reading T Bone’s thoughts on the evolution of folk music, the music he was listening to when he was growing up, and of course his experiences working with the Coens. Other topics under discussion included the American Civil War, George Clooney and Bob Dylan…

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner.

How did you first become aware of the Coen Brothers?

I saw a movie called Blood Simple. And that was shot in Texas, so it was very familiar to me. There were actually people I’d grown up with who were on that crew.

When did you first meet them?

After Blood Simple, I saw Raising Arizona which was their second film. Even more than Blood Simple, it seemed so much like the… it was so familar that after having watched it about ten times I just called Joel up and said, “Hey, what are you doing, I’m coming to New York, you want to have dinner?” It’s the only time in my life I’ve ever just called somebody out of the blue like that. I have a very strong reaction to their work, let me just say that.

Can you describe it?

The detail in it. the details are so smart, so specific. And funny. As I said before, it was as it we’d grown up together. There was too much about it. It seemed like there was already a conversation. Put it this way, I felt a kinship with them. That’s the simple way to say it. so I thought I would just call and say hello, have dinner. We became friends, then about six or seven years later I ran into Joel at an opening in New York and he said, “We’re just starting to do a soundtrack movie, call me tomorrow.” I was at the airport the next day and I called him and he said, “We’re doing a soundtrack movie and we’ve never done one before, but we wondered if you’d come aboard. It’s called The Big Lebowski.” I said, “Yes, of course!” Immediately. That seemed like fun.

Can you tell us about the work you did on Lebowski.

They didn’t want to use a score. They only wanted to use existing material. I was listed as ‘musical archivist’ on that film. Often, that job is called ‘music supervision’, but I’ve never liked the idea of supervising music. So we looked for another name.

You had a more substantial role in O Brother. What can you tell us about that?

We recorded the music some months before we started filming, probably two or three months before we started filming. Or even maybe longer. That was the first time I’d done that, which has become the thing I do most frequently now, record a lot before the shooting begins. All of the film makers I work with consider that the beginning of filmmaking because you’re beginning to create the sound and the tone of the movie. So it’s a thrill to be around at the beginning and record the music. What we did was record all the music for the film and then we were able to put it front to back. I was able to listen to it as an album or as a suite of music, you could hear if the movie played or not. You could hear if the movie slowed down, that sort of thing.

What are your thoughts about the success of the soundtrack now?

It’s been interesting to watch it. So many of the young artists these days in their 20s and mid-20s refer to that record because it was a record that sold 9 or 10 million records, it was a depth-charge, it went down into the ocean, sold 9 or 10 million records but now a lot of the bubbles are floating to the top because people who heard that music when they were in their teens, their early teens, learned about that music from that as I learned about a lot of it from a record called Will The Circle Be Unbroken when we were kids. The thing about this music, this ancient, old music, is you can reinvent it at any time. There is an incredible group of young artists now reinventing it who are so much better than any of us were when we reinventing it. Like who? There are so many, I don’t want to begin. From the very young ones, the Milk Carton Kids, Secret Sisters, there’s a young band called Lake Street Drive, there’s a woman Rhiannon Giddens who’s a major, major talent. Chris Thile is the Louis Armstrong of this generation. Punch Brothers are the Hot Five. Unassailable musicians They’re all drawing from this ancient music and doing the same thing Bill Munroe did, doing the same thing Bob Dylan did, the same thing Marcus Mumford is doing now. The Avett Brothers are another young band drawing from all this stuff, reinventing old sounds.

What is so important about this music in O Brother… and Inside Llewyn Davis?

Historically, music is the way we taught everything. We taught history through music, we taught mathematics through music, we taught language through music, poetry, and this music is the music that grew up out of the ground, it’s the music of the people, the poor people. In particular, in the United States.

What’s your personal connection to the music in this film?

There was an extraordinary rich seam growing out of the East coast and there was a woman named Jean Ritchie who interpreted a lot of old Appalachian music and became the inspiration I would say – Dolly Parton probably wanted to be Jean Ritchie, and Joan Baez drew from Jean Ritchie. So there was this woman I really loved named Jean Ritchie. And then there was a lot of stuff growing up in Texas when I was growing up on the radio, so there by fortune Joan Baez would be on the radio, Bob Dylan would be on the radio. Texas was a wide-open place, so I heard a lot of music from there. My friend Stephen Bruton had a record store, his parents had a record store and they got a lot of stuff from Folkways, so I heard a lot of Appalachian stuff. I have to say, my understanding of the folk music scene left out a lot… I heard Dave Van Ronk very early on. I was certainly familiar with the Beatniks. I have to say, I still consider myself to be a member of the Beat generation. Oh, Tom Paxton was on the radio. “500 Miles” by Peter, Paul And Mary was on the radio. Peter, Paul And Mary did some beautiful versions of those songs. In fact, as far as I know, the folk music scene in those days there were only three venues to play. There was the Hungry Eye in San Francisco, the Gate Of Horn in Chicago and the Gaslight in New York in the early days. So when a folk singer went on tour, that’s where he went. Albert Grossman invented the college circuit by calling Cambridge, all those universities in the north east where they had budgets to present folk events, like they would have cloggers from the Appalachians come up or something, and Grossman started booking Peter, Paul And Mary in there, and he’d add in Muddy Waters and things like that. He was an incredible cat, Albert Grossman. But at any rate, by my understanding of this particular scene was limited.

When did you first go to New York?

The first time I went to New York was 1967 or something. I was producing records in Fort Worth, Texas, and I went up to New York to try to sell them, try to lease them to one of the big companies. That was the first time I saw Greenwich Village, but at the time I was kind of stunned by New York and don’t remember that music of it. I remember the way it looked and felt. I started going back in the early 1970s. It was still the Village then. I don’t know when it probably changed, some time in the Seventies. What were my impressions of the Village? To me, it was Valhalla. It was freedom, it was the big city but it was a small town. There was music all over the place, people looked dangerous. I came from a place were most people looked the same, and in New York a lot of people looked different. I liked that.

What conclusions do you have about the kind of people who were active on the folk scene in the time in which the film takes place?

It’s such a deep question… why is music important? This may seem to have nothing to do with the film whatsoever, but the history of the last 150 years of the United States has everything to do with the Civil War we had and the attempts to resolve that and the attempts to bridge an ocean, really. The reality people were trying to face in the 1950s and 1960s is it’s time actually practise this idea of Civil Rights for all people. That was a time of big time cultural shift and the musicians were carrying the message, they were out in front with the message singing it, leading the culture. In the last 30 years, first the economists took over the culture, then the technologists took over, the engineers took over the culture, and the arts have been sacrificed on the altar of technological advancement. We’re in another time of shift where now we’ve turned into, there is the global economy, etcetera, and now the United States still practises slavery, as we’ve outsourced so much of our labour. So we’re going to have to begin to face who we really we are as a people. Where these songs come from, the songs say things like “the automobile is ruining the country” and the automobile industry was happy to call these people Luddites – go back to your horse and buggy/ the fact we went the direction of the eternal combustion engine rather than an electrical car put this dependence on oil… we have slave labour making oil for us all round the world and if we were paying a small living wage, a friend of mine who’s an economist told me a dollar a day, we would be paying hundreds of dollars a gallon for gasoline. So when we’re told we’re attacked bcause of our freedom, yes we’re attacked because of the freedom we have at the expense of the people we’re enslaving. I’m sure that’s not the answer you wanted…

What I understand from what you’re saying is that the inherent value of folk music is the way it catalogues social history?

Yes, that’s it. That’s right, that’s what I’m, saying. That’s what musicians are supposed to do. We’re supposed to be beholden to no one.

One of the things that’s critical to the film are these notions of authenticity; the way these people present themselves as keepers of a s sacred flame, but have reinvented themselves.

That’s also an important part of it, and very true. That’s part of this country, too, the reinvention of ourselves. As we reinvented music, that becomes a vehicle for that for people, too. Certainly, the history of this country has young people walking out of their homes with nothing but a song and conquering the whole world again and again and again. Our music is our most valuable and most important cultural export in my view. And this is another thing this movie is about is the importance of musicians in this culture. The real life struggles we’ve had not only with finances but identity, having a place to stand at all in the culture. It’s a place of having a couch to sleep on, so to speak.

John Goodman’s character represents another generation of musician. What’s your take on that character?

I loved that character. “I thought you said you were a musician.” [laughs] You don’t just get it from everybody else. You get it from other musicians, too.

Was there a plan in place to mirror the process of O Brother, where there’d be a collection of old songs recorded by newer artists to be released as a soundtrack album in its own right?

No, it was a different idea. The idea was to find actors that can sing the part and shoot it all live. So we pre-recorded everything as we did with O Brother, Were Art Thou but only as a map to make sure that we had everything dope before we got anywhere near the stage. You don’t want to go on stage to go to all that trouble ands all that money and everything and not have something be happening. So we got together, we rehearsed for some time, we got together, we recorded it all. So once again we could listen to the film from beginning to end. But then also we were able to plan, they were able to plan the way they were going to shoot it and the idea was to shoot it all live. Then the actors knew how they sounded already and were able to practise along with what they had already done. They were able to get the… it was like a taped rehearsal for the performance and the performances were all filmed live, without click tracks without any of that, actual coffee house performance, documentary style.

What’s your memory of the shoots themselves?

In the studio, the way I generally work, everything leads up to the moment of the performance and then that’s it, you’re finished. You may go back and do some editing or something like that, but you don’t say, “OK, you’ve got it now, let’s do it five more times.” But because it’s a film, that’s what Oscar had to do. This is the miraculous part of it. He was able to do it again and again and again. That he trained himself. It’s years and years of training. He’s from Juliard and he’s worked hard. We started six months out in front on this film, with this music, creating this character and by the time we got there I was beside him with a stopwatch timing measures to make sure he didn’t speed up or slow down so we could cut between takes. Because even if he got two perfect takes, with different camera shots, if they were different tempos you still couldn’t cut between them. Not only did he have to get the emotional content right, then if he did the songs I would say mostly between, a couple he did three times, mostly five and seven times, so you had to get the emotional content and the pitch and the guitar and all of that right seven times in a row but he had to do it in the same tempo, just with his own internal clock. Which was flawless. He’s a machine. Every take I was there with a stopwatch. Isn’t that wild?

Delivery: more soulful.

That was the part… we put a lot of relative minors in, the E minor change, because he was from Queens, we wanted it to have some of that Queens, doo-wop early R&B about it, so it wasn’t just him being a folk purist. He was bringing other influences into the folk songs to reinvent them.

Do you have a story that best sums up your experiences of working with the Coens?

I can tell you this. When we recorded “Hard Time Killing Floor Blues” for O Brother, we were out there in outside of Los Angeles on a movie ranch. And the guys were laying down on the ground, a couple of cats were sitting down, Clooney I think was laying down, Turturro maybe, Tim Blake Nelson was there. Thomas King was playing that tune. And it was real quiet around the set, everybody was there, everybody was doing there job. People were laughing but it was calm and happy. And we started the scene and the fire was going and the crickets were so loud, if you listen to the record you can hear how loud the crickets are, because that particular recording was recorded live on set.

Photo credit: Jesse Dylan

INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS OPENS IN THE UK ON JANUARY 24; THE SOUNTRACK IS AVAILABLE FROM NONESUCH RECORDS