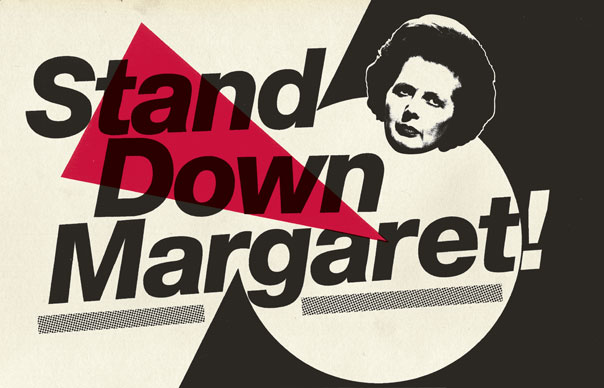

Baby boomers and soixant ouitards will try and convince us that the ’60s was the high-water mark of the protest song, but it was under Thatcher’s 11 years in power that politics really seeped into pop. Somehow, a prime minister whose favourite single was Patti Page’s “How Much Is That Doggy In The Window” found herself name-checked in dozens of songs. Those few pop stars who came out as Conservative supporters – Gary Numan, Tony Hadley, Joan Armatrading, Billy Mackenzie, Lulu, Errol Brown from Hot Chocolate, Jon Moss from Culture Club, Leee John from Imagination – rarely escaped with any credibility.

Some bands who emerged in the early Thatcher years came from a distinct ideological position, with neo-Marxists like The Gang Of Four and Cabaret Voltaire influencing the “entryist” tactics of Heaven 17, Human League and Scritti Politti. More potent was the generation of post-punk and Two-Tone bands, whose protest songs grew organically, angered by the effects of mass unemployment and urban decay. “It’s just Rule One for any songwriter – write what you know,” says Paul Weller. “When you’re confronted by headlines every day about mass unemployment, when you’re seeing devastation of industry and public services, it’s going to find its way into your lyrics. ‘Going Underground’ was a frustrated response to the old saying that people get the government that it deserves – ‘the public gets what the public wants’. That anger fuelled a lot of my material at the time.”

“We never wanted to make despondent music,” says Ali Campbell. “We wanted to make happy music to lift us out of misery, to give us an irie feeling. We were never soapboxers. It’s only because of what was going on in the wake of Thatcher – three and a half million unemployed, cutbacks in public spending, threat of imminent nuclear war – that those early tracks like ‘Madam Medusa’ and ‘One In Ten’ are so bleak.”

“It helped that you had someone who was the very embodiment of evil in power,” says Jerry Dammers. “You have to remember that it was an incredibly politicised era. People were arguing in pubs about monetarism, inflation and unemployment. Everything became political. Not mentioning Thatcher, in a way, was as political as singing about her!”

Malcolm McLaren has since suggested, tongue only slightly in cheek, that punk went hand-in-hand with Thatcherism. Both attacked the postwar consensus, both asserted the primacy of the individual, both served as a model for private enterprise. But punk’s rage was quickly channelled by the left into Rock Against Racism, a coalition first mooted in August 1976 to combat the rise of the National Front and to register disgust at Eric Clapton’s inflammatory onstage comments at the Birmingham Odeon earlier that month. The movement came of age when The Clash headlined an Anti Nazi League Carnival at Hackney’s Victoria Park on April 30, 1978. While some of punk’s swastika-decorated nihilism survived –John Lydon’s socialist baiting, the more politically dubious fringes of Oi! – the spirit of Rock Against Racism dominated pop for much of the 1980s, with several political advocacy events following a similar structure.

In early 1981, Rock Against Racism briefly resurfaced in a small series of gigs, Rock Against Thatcher and Rock Against Sexism. In June 1981 the Glastonbury Festival renamed itself The Glastonbury CND Festival, with the likes of Madness, New Order and Aswad going on to play anti-nuclear benefits. In September 1981, UB40 played several benefits for those arrested in the inner-city riots two months earlier. In 1984 everyone from Test Department to Wham! played fundraisers for striking miners; at the same time dozens of outfits – including The Smiths, The Damned and The Fall – all played in a seemingly endless series of “Save The GLC” concerts in support of Ken Livingstone’s Greater London Council, then on the verge of being abolished by central government. Later events like Artists Against Apartheid followed a similar line.