Mike Skinner’s existence has been transformed by success and fortune. It’s a fortune accrued by observing, in startlingly prosaic detail, a life of Wetherspoons and scams, ashtrays and longing for haughty girls, of cab ranks and late night fumblings. The musical backbeat to Skinner’s tracks always seemed disconnected, however, remote from his own patter, as if emanating from down in the cellar of some nightclub from which he’s excluded, on the wrong side of the velvet rope. Skinner can’t pretend that that is his life nowadays, any more than he could ever pretend he was Nas or Jay-Z or any of his heroes. After the resounding success of 2002’s debut Original Pirate Material and its 2004 follow-up, A Grand Don’t Come For Free, Skinner is a winner. Yet fame hasn’t altered the warp and clunk of his lyrical stance. The setting may have changed, the soundtrack is boosted and richer, grimier yet cleaner, but Skinner’s predicaments remains the same. Take opener “Pranging Out”, in which beats come tumbling out as if from an airing cupboard, with Skinner regretting the consequences of a too-manic time on the road: boozed and cracked out; shivering with paranoia; and, worst of all, realising, “The iron has been on in my house for four fucking weeks.” Skinner’s response to fame is mixed. The title track limps along ruefully, as Skinner reflects on the money he’s squandered. “Hotel Expressionism”, conversely, has the cocksure gait of the Italian Job soundtrack, celebrating on-the-road excess as an art form,. On the rudely funked-up single, “When You Wasn’t Famous”, Skinner stops short of naming names but shows a keen eye for celeb squalor, wondering how the woman he saw getting wasted the night before can look so good on CD:UK the morning after. Closer “Fake Streets Hats” sees Skinner recall an onstage tantrum about supposed bootleg merchandise in Holland which turned out to be official - a wonderful and singularly Streets-ian gesture of self-deprecation. Amid all this are two balladic gestures of sober contrition; the Princean, anti-laddish “All Goes Out The Window” and “Never Been To Church”, which sails perilously close to McCartney’s ”Let It Be”, and on which Skinner fears that he is unworthy of redemption. Not true. The lad may get up to no good, but his entire oeuvre comprises acts of supreme redemption. This is Act Three. By David Stubbs

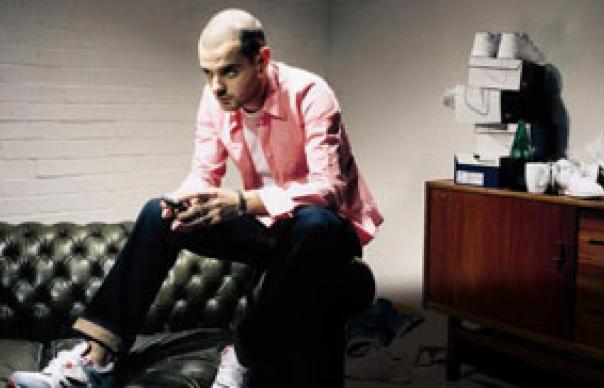

Mike Skinner’s existence has been transformed by success and fortune. It’s a fortune accrued by observing, in startlingly prosaic detail, a life of Wetherspoons and scams, ashtrays and longing for haughty girls, of cab ranks and late night fumblings. The musical backbeat to Skinner’s tracks always seemed disconnected, however, remote from his own patter, as if emanating from down in the cellar of some nightclub from which he’s excluded, on the wrong side of the velvet rope.

Skinner can’t pretend that that is his life nowadays, any more than he could ever pretend he was Nas or Jay-Z or any of his heroes. After the resounding success of 2002’s debut Original Pirate Material and its 2004 follow-up, A Grand Don’t Come For Free, Skinner is a winner. Yet fame hasn’t altered the warp and clunk of his lyrical stance. The setting may have changed, the soundtrack is boosted and richer, grimier yet cleaner, but Skinner’s predicaments remains the same. Take opener “Pranging Out”, in which beats come tumbling out as if from an airing cupboard, with Skinner regretting the consequences of a too-manic time on the road: boozed and cracked out; shivering with paranoia; and, worst of all, realising, “The iron has been on in my house for four fucking weeks.”

Skinner’s response to fame is mixed. The title track limps along ruefully, as Skinner reflects on the money he’s squandered. “Hotel Expressionism”, conversely, has the cocksure gait of the Italian Job soundtrack, celebrating on-the-road excess as an art form,. On the rudely funked-up single, “When You Wasn’t Famous”, Skinner stops short of naming names but shows a keen eye for celeb squalor, wondering how the woman he saw getting wasted the night before can look so good on CD:UK the morning after. Closer “Fake Streets Hats” sees Skinner recall an onstage tantrum about supposed bootleg merchandise in Holland which turned out to be official – a wonderful and singularly Streets-ian gesture of self-deprecation.

Amid all this are two balladic gestures of sober contrition; the Princean, anti-laddish “All Goes Out The Window” and “Never Been To Church”, which sails perilously close to McCartney’s ”Let It Be”, and on which Skinner fears that he is unworthy of redemption. Not true. The lad may get up to no good, but his entire oeuvre comprises acts of supreme redemption. This is Act Three.

By David Stubbs