If DJ Kool Herc is generally considered the godfather of hip-hop, it can be argued that Cornell Benjamin was its first martyr. Benjamin was neither a musician nor a DJ. Rather, he was a drugs counsellor and appointed peacemaker who, under the aegis of New York street gang the Ghetto Brothers, was despatched to broker a truce during the vicious turf wars of the early ‘70s. He was killed by a rival gang.

Benjamin’s murder is the pivotal moment in Rubble Kings, Shan Nicholson’s engrossing documentary about gang culture in New York, largely centred around the South Bronx of the ‘60s and ‘70s. His death brought years of brutality to a head, resulting in an inter-gang treaty – the historic Hoe Avenue Peace Meeting of December 1971 – that led to a shift of emphasis among the tribal factions. Violence was out, music was in. Opposing gangs jammed with one another at block parties. DJs became the new community leaders. And crucially, the culture of intimidation found a creative outlet in dance battles and DJ match-ups. Hip-hop, as one ex-gang member puts it, “calmed the savage beast.”

The birth of hip-hop serves as the resting point for Rubble Kings’ narrative arc. But this is primarily a film about the socio-economic conditions that gave rise to gang culture, the fierce allegiances therein and the eventual realisation that, unless they took drastic action, their only achievement would be to wipe themselves out completely.

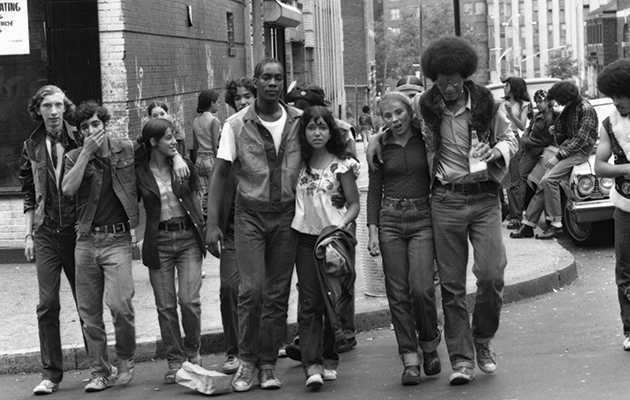

Nicholson uses archive footage, graphic novel-style illustrations and plenty of talking heads (mostly former gang members) to tell the story of how the Bronx went from picturesque borough to the ultimate symbol of civic decay in just a few short years. America’s grand vision of urban renewal failed to reach the Bronx at all. Houses were torn down, landlords began torching their own buildings to claim insurance and the poor were left behind as the moneyed classes moved out.

Outlaws sprung up from the rubble, raising hell and rigorously marking out their territory. The choice was stark: either join a gang or become a victim. Each clan had its own hierarchy, from Presidents and Vice-Presidents to Warlords and Gestapo agents, whose task it was to mete out severe punishment to members guilty of contravening their strict code. Anyone wanting to join a gang was required to undertake a ruthless initiation rite. The most common of these was the Apache Line, in which the prospective recruit made his way though two flanks of gang members while being pummelled by a sea of fists. If you made it out in one piece, unconscious or otherwise, you were in.

The Ghetto Brothers’ method involved slipping a 45 on the turntable and pitching the recruit in a fist fight against three hardcore members for the duration of the song. Bloodlust often took over. Joint leader ‘Yellow Benjy’ Melendez recalls one of his charges eagerly returning from the local store with a full album, hoping to see the hapless guy’s jaw break.

The testimony of Melendez, alongside fellow Ghetto Brothers chief Carlos ‘Karate Charlie’ Suarez, is at the heart of Rubble Kings. Both men exude charisma. Former colleagues describe them as yin and yang – Suarez the pragmatist ex-Marine who styled himself on the Japanese Bushido; Melendez the impassioned orator who sought a way out of the malaise.

There were well over a hundred gangs in New York, all with fabulous names – Savage Nomads, Ebony Dukes, Young Dynamite, Seven Immortals, Harlem Turks, Golden Guineas – but the Ghetto Brothers were unique in that they were driven by a political consciousness, using the media to fan the cause (there’s fascinating footage of a leadership summit on The David Susskind Show). They were intent on helping the community around them, be it providing essentials like food and clothes, scrubbing graffiti or warning people off drugs. They were also a very handy Latin-funk band, whose 1971 opus Power-Fuerza was finally granted a proper release in 2012.

At just 70 minutes in length, Rubble Kings doesn’t hang about. But it nevertheless manages to cover an impressive amount of ground, the hip-hop fraternity represented by Kool Herc, Jazzy Jay and the key figure of Afrika Bambaataa. The latter was a warlord in the Black Spades before co-opting them into Universal Zulu Nation: “The first black force to promote positivity through music.”

This is far more than just a story about survivalist machismo. Rubble Kings offers a powerful reminder of the sheer resilience of the human spirit in the face of terrible odds. And, more impressively, the ability to create something meaningful from utter chaos.

The History Of Rock – a brand new monthly magazine from the makers of Uncut – a brand new monthly magazine from the makers of Uncut – is now on sale in the UK. Click here for more details.

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.