Since the mid-1950s, Peter Watkins has been making radical and challenging films that have mixed improvisational, dramatic and documentary techniques to incredible and often innovative effect. You'd know him best for The War Game, a nightmarish BBC semi-documentary from 1966 about the effects of a nuclear strike on Britain, which was banned from broadcast. Since then, he's lived in self-imposed exile while his work has become increasingly marginalized, rarely seen outside retrospectives or film festivals. Punishment Park is his only American movie, made in 1971 as the social and political turmoil of the era reached a peak. Here, Watkins envisaged an authoritarian clampdown by the Nixon administration on radicals and activists. Stripped of their rights, they're presented with a stark choice by establishment tribunals: either lengthy prison sentences, or running the gauntlet of Punishment Park, a three-day marathon through the high desert with armed National Guardsmen on their trail. In a nutshell, it's Battle Royale with peaceniks, though the tribunal hearings are at least as important to Watkins as the action sequences he cuts into them. Anticipating the conventions of reality TV, the film shows 'ordinary people' (at least, non-professional actors) reacting to a highly charged situation in ways that are always credible and often disturbing. There is one story that Watkins halted filming at one point because he was worried that the actors playing the National Guardsmen had loaded real shells into their rifles. The extent to which Watkins found the pulse of the times can be measured in the extreme hostility of contemporaneous US reviews. The film was pulled after only four days in New York and has rarely screened since. Thirty years on, the counter culture rhetoric sounds strange to our ears - but in other ways this film is more relevant than ever. In the light of Guantanamo Bay, Abu Ghraib and the Patriot Act, the Bush administration's blatant disregard not only for civil liberties but for human rights, Watkins' paranoid metaphor feels all too valid. Screening with his other movies - including The War Game and the Vietnam allegory Culloden - as part of a retrospective at London's ICA, this is a valuable opportunity to explore the work of one of the most overlooked, but important, film makers of his generation. By Tom Charity

Since the mid-1950s, Peter Watkins has been making radical and challenging films that have mixed improvisational, dramatic and documentary techniques to incredible and often innovative effect. You’d know him best for The War Game, a nightmarish BBC semi-documentary from 1966 about the effects of a nuclear strike on Britain, which was banned from broadcast. Since then, he’s lived in self-imposed exile while his work has become increasingly marginalized, rarely seen outside retrospectives or film festivals.

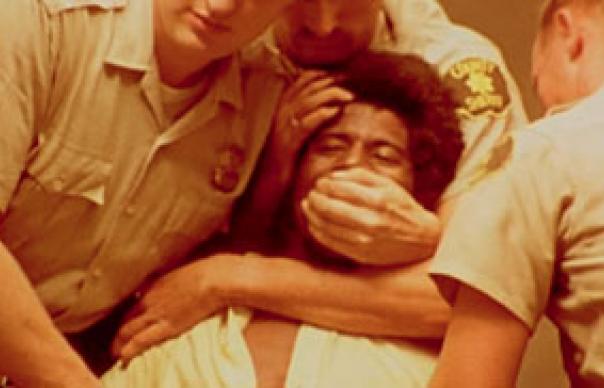

Punishment Park is his only American movie, made in 1971 as the social and political turmoil of the era reached a peak. Here, Watkins envisaged an authoritarian clampdown by the Nixon administration on radicals and activists. Stripped of their rights, they’re presented with a stark choice by establishment tribunals: either lengthy prison sentences, or running the gauntlet of Punishment Park, a three-day marathon through the high desert with armed National Guardsmen on their trail.

In a nutshell, it’s Battle Royale with peaceniks, though the tribunal hearings are at least as important to Watkins as the action sequences he cuts into them. Anticipating the conventions of reality TV, the film shows ‘ordinary people’ (at least, non-professional actors) reacting to a highly charged situation in ways that are always credible and often disturbing. There is one story that Watkins halted filming at one point because he was worried that the actors playing the National Guardsmen had loaded real shells into their rifles.

The extent to which Watkins found the pulse of the times can be measured in the extreme hostility of contemporaneous US reviews. The film was pulled after only four days in New York and has rarely screened since. Thirty years on, the counter culture rhetoric sounds strange to our ears – but in other ways this film is more relevant than ever. In the light of Guantanamo Bay, Abu Ghraib and the Patriot Act, the Bush administration’s blatant disregard not only for civil liberties but for human rights, Watkins’ paranoid metaphor feels all too valid.

Screening with his other movies – including The War Game and the Vietnam allegory Culloden – as part of a retrospective at London’s ICA, this is a valuable opportunity to explore the work of one of the most overlooked, but important, film makers of his generation.

By Tom Charity