Patti Smith’s independent debut “Piss Factory” came out in 1974; the following November, manager Terry Ork put out Television’s first single, “Little Johnny Jewel”, on his own label. They were the first flowerings of the New York renaissance.

By 1976, big labels had carved up the CBGBs underground; Television went to Elektra, Patti Smith to Arista, Talking Heads joined the Ramones on Sire, Blondie went to Private Stock and then Chrysalis. It was a feeding frenzy that drew aspiring oddballs to the Bowery in droves.

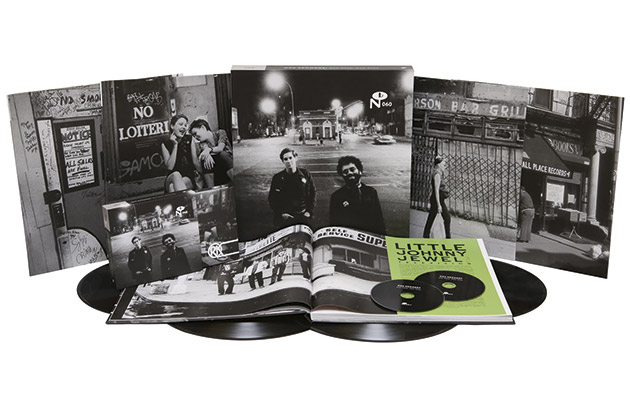

For a few months between 1976 and mid-1977, Ork – the scene’s only active independent – had their pick of the new arrivals, snaring Richard Hell & The Voidoids, Alex Chilton, a pre-dBs Chris Stamey and The Feelies among others. This lovingly assembled, 49-track collection pieces together the projects – completed, abandoned and otherwise – that Ork helped to instigate, as the hustler-cum-superfan and sometime business partner Charles Ball seized their moment.

William Terry Collins, AKA Terry Ork, had come to New York from San Diego in the late 1960s, working for Andy Warhol’s Inter/View magazine for a while before winding up as part-time manager of film knick-knack shop, Cinemabilia. Regaling his circle with the tale of how he once gave Lou Reed head, he set about creating a superstar factory of his own.

He completed the wiring of Television by introducing Cinemabilia employee Hell and Tom Verlaine to his leechy flatmate, guitarist Richard Lloyd (“There was a great love between us,” Lloyd remembered of Ork. “For him it was romantic, for me it was platonic”). Ork managed Television until their ascent demanded a more astute approach, but he kept busy, releasing the American version of Hell’s “Blank Generation” EP, before finding one member of bowl-cutted power-poppers the Marbles working at Cinemabilia, and making 1976’s gloriously feeble “Red Lights” his third release.

Preppy aesthete Ball kept the ball rolling. “Terry was always the public face of the label, a bon vivant more interested in chasing around Richard Lloyd than the music itself,” music journalist and Ork insider Roy Trakin tells Uncut. “Charles, on the other hand, was immersed in culture theory, Jean Luc-Godard and the mechanics of actually recording music.”

Excited by some audio verité demoes recorded in Memphis by journalist-turned-producer Jon Tiven, Ball and Ork hauled Alex Chilton up to their studio of choice ¬ Trod Nossel in Connecticut – to put down the five tracks that make up 1977’s surly “Singer Not The Song” EP. Chilton’s stag-horned “Free Again” and the excitable “Take Me Home And Make Me Like It” are deliriously grubby, though his excitable whoop of “call me a slut in front of your family” on the latter seemed a little far-fetched; so poor during his couch-surfing year in New York that for a while he did not even own shoes, Chilton was in no state to be introduced to anyone’s parents.

Almost as an afterthought, Ork simultaneously put out “Girl” by Tiven’s band Prix – a delicious analogue to Chris Bell’s Big Star contributions. Tiven was not destined to be Chilton’s new musical foil, though, his time as a sideman ending when the singer tried to stub a cigarette out in his face. Stamey had a much more successful dalliance with the ex-Box Top, Chilton helping piece together the North Carolina moptop’s skinny-tie thunderbolt “The Summer Sun” – the final Ork release of 1977.

With the label momentarily buoyant, a major-label distribution deal was sought, but Ork and Ball’s failure to snare one meant a raft of projects were mothballed. A Rolling Stones tribute LP vanished without trace, and tapes of The H-Bombs – featuring Stamey’s future dBs foil Peter Holsapple – and Lester Bangs were farmed out to other labels. A first release from New Jersey’s splendidly uptight Feelies also went begging, the frenetic version of “Fa Ce La” here canned at the band’s request, though the song resurfaced as their Rough Trade debut two years later.

Ball went his own way, his Lust/Unlust imprint later giving first exposure to some of New York’s most abrasive outfits. He died in 2012. “Ork and Ball’s split was not an amicable one,” Trakin remembers. “I’m not sure if they ever reconciled as two strong-willed personalities who blamed one another for their massive, if-only fail.”

Ork, meanwhile, enlisted new financial backers – Hassidic Jews with decidedly unorthodox heroin habits. “Little Johnny Jewel” was repressed as a 12”, but the reactivated label evidently found the CBGBs waters of 1979 much over-fished. Ork’s final releases featured uninspiring cock-rock from the Idols – featuring ex-New York Dolls Arthur Kane and Jerry Nolan – and unremarkable one-offs from the Revelons and the Student Teachers. The last Ork release – former Dead Boy Cheetah Chrome’s “Still Wanna Die” – was an Iggy Stardust glam-punk classic, much undermined by an incongruous flower-power sleeve.

Ork clung on New York for a while, managing hardcore band the Worst, before fading into legend. He wrote for a West Coast arts magazine as Noah Ford, and was jailed from 1991 to 1994, for passport fraud, cheque fraud or Andy Warhol fraud, according to conflicting reports. He died of colon cancer in 2004.

“I like Terry,” Verlaine said in 1979, showing uncommon generosity as he summed up Ork. “He has no business sense, but he’s a great guy.” At the bottom of the rear sleeve of Television’s era-defining Marquee Moon is a note reading: “This album is dedicated to William Terry Ork.” Like this collection, a small credit where it was due.

EXTRAS 8/10: A pleasantly bitchy book gives all Ork acts their due, a raft of rare tracks completing the picture. Prix offcuts are essential listening for Big Star fetishists, while unreleased Ork singles by Patti Smith-worshippers the Erasers, and angry loner Kenneth Higney feature, along with both sides of Link Cromwell’s “Crazy Like A Fox” – the 1966 Brit-invasion knock-off voiced by Patti Smith Group guitarist Lenny Kaye, which was re-circulated by Ork. Another discovery is the first version of Richard Lloyd’s sparkly “I Thought You Wanted To Know”, later re-voiced and released by Stamey on his Car label when it emerged that the object of Ork’s affections was still under contract at Elektra.

Q&A

dB Chris Stamey and Feelie Glenn Mercer remember their Ork years

How would you describe Terry Ork?

Chris Stamey: I never met Jerry Garcia, but Terry always reminded me of what I imagined Garcia might be like – very upbeat and positive, a dreamer. He never seemed like a businessman, but he was a great cheerleader and he had a vision and this really mattered to everyone at the time. Both he and Charles Ball came from a film background, not a musical one, which was interesting. And you have to remember that it wasn’t just Terry – Charles was a huge part of it all.

Glenn Mercer: We had played an audition night at CBGB and the house soundman, Mark Abel, told us that he planned to invite Ork to our next gig because he thought Terry would like our sound. I don’t remember that much about it, but I think I was surprised by the way he looked. You didn’t see too many beards or much long hair among the punk rock crowd. We didn’t talk much about music, actually. He was more of a movie fan and talked more about foreign films than he did about music.

Was Television’s success a big factor in bands coming to New York in this period?

Chris Stamey: I’d seen Television play at CBs in the summer of 1975 and was blown away. This was directly a big reason for my move to New York – no question about it. It was the kind of music I wanted to make – transcendent, electric and immediate. I’d made a false leap in thinking that there were lots of bands that sounded like them – in actual fact, they were the sole flagbearers of that kind of playing at the time, that kind of “punk jazz”, I guess you could call it. And honestly, I never found any other bands on the scene that held a candle to them, although sometimes playing with Alex would have some of that flavour, later on.

Glenn Mercer: More than anything, being original and unique was what was required in that musical landscape. I doubt that Terry was grooming The Feelies as the new Television. He was smart enough to realise that we weren’t really that similar to Television. I also think that he knew that the New York underground music scene probably wouldn’t ever become mainstream and there wasn’t an ideal model for success.

There was not much money around, but Ork seemed to have a lot of ideas on the go, no?

Chris Stamey: Well, we didn’t need all that much money. I do remember having to walk everywhere and relying on major-label press parties for meals sometimes. It just seemed bohemian; Rimbaud and Nerval were in the air – it was a Left Bank scene in that way. Alex Chilton was pretty much unknown to the CBs scene – the third Big Star record only existed on a few bootleg cassettes. He was in fine shape, just a bit shy and trying to get over a major romance that was ending. His problem, as I see it, was that he was totally broke that year in New York City. Ork tried to help for a while but didn’t have any money really. People would not buy him dinner, but they would buy him unlimited drinks. So he drank instead of ate.

Glenn Mercer: I remember Terry having an idea to record “Chinese Rocks” with the ‘Ork Orchestra’, since the Ramones didn’t initially want to use the song. At the session, there was Bob Quine, Jody Harris, Chris Frantz and Dee Dee Ramone. I played bass because Dee Dee only wanted to sing. I also remember often hanging out with Richard Lloyd at Terry’s place. In general, the bands supported each other and there was a sense of ‘us v them’ in regard to the music in the mainstream.

Do you remember Terry Ork and Charles Ball fondly?

Glenn Mercer: I have many fond memories of both Terry and Charles, and of that time period. Unfortunately, we lost touch after we stopped working together. The last time I saw Terry was at the premier of the film Smithereens in 1982, but we didn’t get a chance to talk much then.

Chris Stamey: Terry helped The dB’s in talks with Warner Bros, UK, which was great. It wasn’t so great that the talks fell apart when his deal stopped, leaving us with some unpaid studio bills. But this worked out in the end, resulting in the first dB’s record, Stands For deciBels. This record probably would not have existed without Terry’s UK connections. Terry always seemed genuinely interested in helping the musicians and bands he liked. It seems odd now, but rock musicians doing ‘non-commercial’ music had not yet realised that it was possible to bypass the commercial labels.

INTERVIEWS BY JIM WIRTH

The History Of Rock – a brand new monthly magazine from the makers of Uncut – a brand new monthly magazine from the makers of Uncut – is now on sale in the UK. Click here for more details.

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.