Directed by: Julian Schnabel Starring: Lou Reed, Steve Hunter, Emmanuelle Seigner By the end of 1972, after a decade of cult acclaim and commercial failure, Lou Reed was, finally, implausibly, a bona fide pop star. With “Walk On The Wild Side” in the Top 10, Transformer riding high and Velvets fans such as David Bowie and Roxy Music marking a sea change in 1970s’ rock, RCA fancied they had a potential superstar on their hands. For the follow up, Lou hooked up with Alice Cooper's prodigy producer, Bob Ezrin, and a superstar band featuring Stevie Winwood, Jack Bruce, Aynsley Dunbar and Steve Hunter. Not for the last time, Reed confounded everyone. Berlin was an audacious, orchestrated song cycle of “love, jealousy, rage and loss” – something like Hubert Selby Jr's Last Exit To Brooklyn scored by the Bernard Herrmann of Taxi Driver. But it received, it’s fair to say, some pretty terrible reviews. The suits at RCA were horrified – accusing their artist of failing to make a proper Lou Reed record. Reed had theatrical ambitions for the album – it had been trailed by Ezrin as a “film for the ears” – and reportedly met with Warhol for talks about mounting the album as a Broadway production. But the plans were scuppered by the scornful critical reception. But 30-odd years later, it now seems that if Lou’s ambition to “bring the sensitivities of the novel to rock and roll” was ever properly realised, it was with this squalid story of seedy, soul-sick lovers, Caroline and Jim, falling apart in a divided Berlin. Encouraged by Susan Feldman of Brooklyn’s St Anne’s Warehouse, Reed finally brought Berlin to the stage in December 2006, for a show, filmed over five nights by Ellen Kuras, directed by Julian Schnabel and now given a full theatrical release ahead of British shows this summer. We can only dream of the grand guignol cabaret or blankly camp torpor Warhol might have fashioned from Berlin. But just as Reed is no longer the emaciated albino, shooting up on stage, with Nazi crosses shaved onto his skull – rather, a stocky sixty-something who looks like he might be Fabio Cappello's earnest older brother – this Berlin is comparatively sober. Julian Schnabel’s set is marbled with the “greenish walls” of “Lady Day”. His daughter, Lola, contributes some short, impressionistic filmic interludes, featuring the Nico-iconic Emmanuelle Seigner (the star of Schnabel's The Diving Bell And The Butterfly and Mrs Roman Polanski) as Caroline, the “Germanic queen”, stumbling her way to hell via the dive bars and beat hotels. And the Spanish installation artist Alejandro Garmendia contrives a short, unsettling scene of furniture whirling drunkenly around a drowned bedroom, to accompany the eerie, obituary calm of “The Bed”. But otherwise, this is a pretty straightforward rock concert film, focusing on a superlative band performing the album, in sequence. A lot of the fascination of the film comes down to the fact, that since an accident a couple of years ago, Lou can no longer wear shades. And because the cameras keep such a close watch on that unusually exposed granite poker face, catching the merest flickers of emotion, it’s apparent that he actually seems to be… enjoying himself. He only played acoustic guitar on Ezrin’s darkly symphonic album production, but here he has strapped on the electric and seems to be having a ball leading a band featuring Steve Hunter from the original recording, Fernando Saunders and Tony Smith from his current outfit, and a backing choir starring Antony Hegarty (stunning on a solo encore of “Candy Says”), Sharon Jones of The Dap-Kings and members of the Brooklyn Youth Chorus. In fact it’s almost distracting, watching Reed and Hunter trading shit-kicking jam-session licks, while Ezrin himself, in full deranged conductor mode, leads the chamber orchestra, as the songs chart their pitiless, relentless spiral downwards through dismay, decay, and ultimate doom. But the brassy bombast of the album’s first side – “Lady Day”, “Men Of Good Fortune”, “How Do You Think It Feels?” – gives way to the mournful second half, and the performance comes into its own with “The Kids”: Lou never better then as the dispassionate observer, the waterboy “with no words to say”. There are few things in Reed's career, or even the history of rock, as chilling as the children (reputedly Ezrin's own) screaming for their mother as they’re taken into care. At the screening I was at, several people felt compelled to walk out. But they missed the strangest, strongest thing about the film – the sense of resolution. Not necessarily in the music: you could never really reasonably describe a story detailing drug addiction, prostitution, domestic violence and suicide as a feel-good evening out. But by the end of “Sad Song”, even as Lou is sighing and snarling that “somebody else would have broken both her arms”, as the strings ascend ever upwards, there’s an inescapable, perverse sense of triumph. Not that he would ever admit to anything so shabby or shameless as a sense of vindication, but, decades after the critical and commercial fiasco of its release, Lou Reed seems to be relishing every second of Berlin’s belated acclaim. STEPHEN TROUSSE

Directed by: Julian Schnabel Starring: Lou Reed, Steve Hunter, Emmanuelle Seigner

By the end of 1972, after a decade of cult acclaim and commercial failure, Lou Reed was, finally, implausibly, a bona fide pop star. With “Walk On The Wild Side” in the Top 10, Transformer riding high and Velvets fans such as David Bowie and Roxy Music marking a sea change in 1970s’ rock, RCA fancied they had a potential superstar on their hands. For the follow up, Lou hooked up with Alice Cooper’s prodigy producer, Bob Ezrin, and a superstar band featuring Stevie Winwood, Jack Bruce, Aynsley Dunbar and Steve Hunter.

Not for the last time, Reed confounded everyone. Berlin was an audacious, orchestrated song cycle of “love, jealousy, rage and loss” – something like Hubert Selby Jr’s Last Exit To Brooklyn scored by the Bernard Herrmann of Taxi Driver. But it received, it’s fair to say, some pretty terrible reviews. The suits at RCA were horrified – accusing their artist of failing to make a proper Lou Reed record.

Reed had theatrical ambitions for the album – it had been trailed by Ezrin as a “film for the ears” – and reportedly met with Warhol for talks about mounting the album as a Broadway production. But the plans were scuppered by the scornful critical reception. But 30-odd years later, it now seems that if Lou’s ambition to “bring the sensitivities of the novel to rock and roll” was ever properly realised, it was with this squalid story of seedy, soul-sick lovers, Caroline and Jim, falling apart in a divided Berlin. Encouraged by Susan Feldman of Brooklyn’s St Anne’s Warehouse, Reed finally brought Berlin to the stage in December 2006, for a show, filmed over five nights by Ellen Kuras, directed by Julian Schnabel and now given a full theatrical release ahead of British shows this summer.

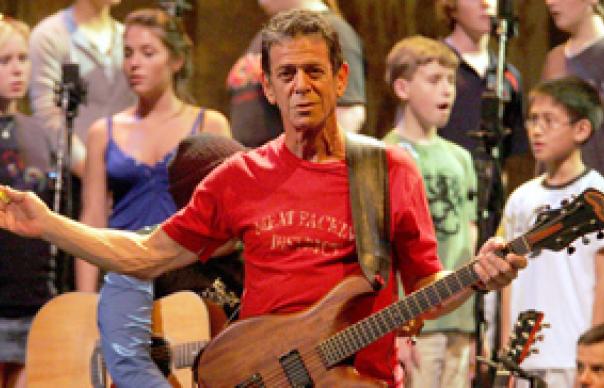

We can only dream of the grand guignol cabaret or blankly camp torpor Warhol might have fashioned from Berlin. But just as Reed is no longer the emaciated albino, shooting up on stage, with Nazi crosses shaved onto his skull – rather, a stocky sixty-something who looks like he might be Fabio Cappello’s earnest older brother – this Berlin is comparatively sober. Julian Schnabel’s set is marbled with the “greenish walls” of “Lady Day”.

His daughter, Lola, contributes some short, impressionistic filmic interludes, featuring the Nico-iconic Emmanuelle Seigner (the star of Schnabel’s The Diving Bell And The Butterfly and Mrs Roman Polanski) as Caroline, the “Germanic queen”, stumbling her way to hell via the dive bars and beat hotels. And the Spanish installation artist Alejandro Garmendia contrives a short, unsettling scene of furniture whirling drunkenly around a drowned bedroom, to accompany the eerie, obituary calm of “The Bed”.

But otherwise, this is a pretty straightforward rock concert film, focusing on a superlative band performing the album, in sequence. A lot of the fascination of the film comes down to the fact, that since an accident a couple of years ago, Lou can no longer wear shades. And because the cameras keep such a close watch on that unusually exposed granite poker face, catching the merest flickers of emotion, it’s apparent that he actually seems to be… enjoying himself. He only played acoustic guitar on Ezrin’s darkly symphonic album production, but here he has strapped on the electric and seems to be having a ball leading a band featuring Steve Hunter from the original recording, Fernando Saunders and Tony Smith from his current outfit, and a backing choir starring Antony Hegarty (stunning on a solo encore of “Candy Says”), Sharon Jones of The Dap-Kings and members of the Brooklyn Youth Chorus. In fact it’s almost distracting, watching Reed and Hunter trading shit-kicking jam-session licks, while Ezrin himself, in full deranged conductor mode, leads the chamber orchestra, as the songs chart their pitiless, relentless spiral downwards through dismay, decay, and ultimate doom.

But the brassy bombast of the album’s first side – “Lady Day”, “Men Of Good Fortune”, “How Do You Think It Feels?” – gives way to the mournful second half, and the performance comes into its own with “The Kids”: Lou never better then as the dispassionate observer, the waterboy “with no words to say”. There are few things in Reed’s career, or even the history of rock, as chilling as the children (reputedly Ezrin’s own) screaming for their mother as they’re taken into care. At the screening I was at, several people felt compelled to walk out.

But they missed the strangest, strongest thing about the film – the sense of resolution. Not necessarily in the music: you could never really reasonably describe a story detailing drug addiction, prostitution, domestic violence and suicide as a feel-good evening out. But by the end of “Sad Song”, even as Lou is sighing and snarling that “somebody else would have broken both her arms”, as the strings ascend ever upwards, there’s an inescapable, perverse sense of triumph. Not that he would ever admit to anything so shabby or shameless as a sense of vindication, but, decades after the critical and commercial fiasco of its release, Lou Reed seems to be relishing every second of Berlin’s belated acclaim.

STEPHEN TROUSSE