When Steve Verroca encountered Link Wray playing guitar at a club in Virginia towards the end of the 1960s he was thrilled and shocked. The place was full of drunken sailors and hookers, none of whom were really listening to Wray, who was stationed on a small stage beside the bar with his brother Doug on drums, and Billy Hodges on keyboards and bass.

“It was smoky and loud,” says Verroca, “and Link was up there, pretty much like a human jukebox, nobody was playing any attention. I was glad that I was watching the immortal Link Wray play, and very sad that he was playing in a rathole like that.”

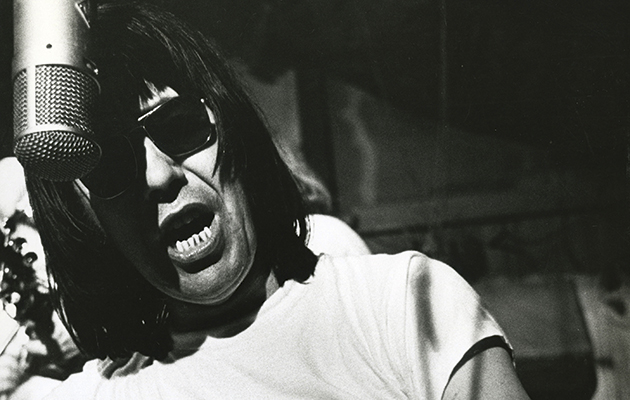

But Verroca had a plan, and it would lead to an extraordinary diversion in Wray’s stalled career. It was not, perhaps, as revolutionary as the recordings which made his name, starting with the malign electricity of his 1958 hit, “Rumble”. But there is a case to be made for the albums which emerged from Wray’s collaboration with Verroca. They didn’t exactly invent Americana; the recordings are too wild to be constrained by a generic straightjacket. But in diverting Wray’s energies back to the music which has first inspired him – hard country, hellfire gospel, blues – they showed how rock’n’roll could renew itself by reigniting its primal spirit. You only have to listen to Wray’s two attacks on “In The Pines” to understand that Wray’s shack recordings are the staging post between Lead Belly and Nirvana Unplugged. The fidelity, it’s true, is not high. Wray sings like one-lunged Jagger, and the guitar fizzes like an ultraviolet insect exterminator. It’s punk before punk, delivered with the momentum of a runaway train.

Granted, few people cared at the time. Between 1971-3, when the records were released, rock was still struggling to absorb The Rumble Man’s earlier innovations – power chords and distortion – but viewed from here, the naked beauty of the recordings Wray made at the family farm in Accokeek, Maryland is obvious.

Wray’s initial reluctance about the project was understandable. The music business had moved on since his brief moment of exposure, and as an innovator he had never really been rewarded. Link’s brother Ray took care of the money, leaving Link to take care of the music. Wray was over 40, with no realistic expectation of a return to currency. Whatever market there had been for instrumental rock’n’roll had evaporated. But still, Wray had his pride. If he was going to make another record, more than a decade after his last, he was determined that it should be done properly, in a high-end studio.

Everything changed when Wray showed Verroca his rehearsal space. In retrospect, it has become known as the 3-Track Shack, a reference to the basic Ampex recorder in the corner, but not much effort had been taken to disguise its previous function. It was a chicken coop which had been converted into a rehearsal space, when the inconvenience of hosting a recording studio in the basement of the main house became too great. The shack was not designed with comfort in mind, and little thought had been given to acoustics. The roof leaked, playing havoc with the tuning of the piano.

In the sleeve notes to this reissue, Wray gives his views on the shack in a 1971 interview. “We just sit down, start the tape and play what we want. If it’s good it’s good, and if it’s bad it’s bad. There’s no electronics, just the real nitty gritty, honest music. When I’d be working in the studios in New York it’d be like working in a cathedral. You get these studios with 16 tracks and 24 tracks and you get drunk with power. You start adding more and more to what you have and in the end it’s becoming mechanical music, head music, all planned out. The feeling comes first. Feeling is the secret, not some jumped up sound.”

In that statement, Wray was both ahead of and behind the times. But the focus on inspiration and spontaneity produced great results. Verroca did a deal for five albums. In the end, only three emerged. The first, Link Wray, is an untamed, feral country rock album, with strung-out Stones-style ballads (“Take Me Home Jesus”), violent story songs (“Fallin’ Rain”), concluding with a swampy take on Willie Dixon’s “Tail Dragger”.

The second album, Mordicai Jones, is a more polished affair, with Gene Johnson taking vocal duties after Bobby Howard took fright in front of the microphone. Johnson is a better singer than Wray, technically, and there’s nothing wrong with the songs (“The Coca Cola Sign Blinds My Eyes” is especially fine), but there is a sense that as Verroca and Wray got used to their limitations the fire dimmed slightly. The third album, Beans And Fatback, was sometimes dismissed by Wray, but it matches the spirit of the first album, and adds muscle. As well as those assaults on “In The Pines” (one labelled as “Georgia Pines”), there’s the swaggering beat of “I’m So Glad, I’m Proud” which succeeds, even though Wray appears to be singing on a different continent to his swaggering guitar. And “Hobo Man” is a gorgeous, strung-out ballad in the Stones gospel mode which shows that Wray’s guitar could evince subtlety as well as raw power.

Ultimately, Wray was right. In 1971, no-one was crying out for a new Link Wray album. The records didn’t sell and Wray took his new direction west, collaborating with Jerry Garcia and others on the equally unsuccessful Be What You Want To. In truth, some of the magic was lost when Wray started to move in more elevated circumstances. The shack recordings were all about making do and making it up, and working within constraints helped focus Wray’s creativity. Verroca likes to joke that “the shack was so small, you had to go outside to change your mind.” At their best, these sessions capture a man rediscovering that he was right all along.

Q&A

Producer Steve Verroca on working with Link Wray

How did you persuade Link to work with you?

At the beginning, Link didn’t like me. Link was like, ‘What the fuck do you want?’ He was the guy who invented rock’n’roll, and he was broke. He couldn’t even feed his family. So he was very sceptical. He barely shook my hand, he didn’t want to know about me. He said: “You want to produce an album? Who the hell wants an album of Link Wray’s music any more?” This was the ’60s, man, it was The Beatles, the Stones and all that stuff. And I said, “Well, Link, these are the people who idolise you.” He didn’t believe it – he thought I was just bullshitting him. I went back to New York and I began getting all these phone calls from Link, he was so excited. We wrote most of the material on the Polydor album, the Indian head album (Link Wray) on the phone. Me and him together at all kinds of hours. He’d call me at three in the morning.

Why did you decide to record in the shack?

To me, it looked like that was his home. He was awesome in there. So I thought, how am I going to convince him that we’re going to record here, in this chicken coop? He didn’t care for the idea at all. So we agreed that we would do a couple of songs, and if they were not master quality, I would book a studio in New York. We did a couple of songs, and Link and his brother Doug, and a couple of other guys trooped over, and Link said, “Man, this is the best stuff I’ve ever done. Let’s do it here.”

What was he like to work with?

There was nothing very conventional about Link. He made his own equipment. He bought cheap Japanese guitars from the loan shop and he worked on them. The first, and the only, amp we used, he made out of an old radio. He got some tubes and he built a wood box, and he put some industrial cotton in the box and a 10-inch speaker, and it sounded incredible. There was no buttons, no high, no low, no bass, no treble, just one way: boom! The sound was so huge that it was impossible to record. The amp, the Link Wray sound, leaked into the drum track, it leaked into the piano track. So we decided to put the amp outside in the yard. The only way we could do that was to mic it through the window and it gave us kind of a special sound. We were trying different things. The piano was all rusted, because the shack in winter leaked. We had all blankets all over the place and we miked the piano under the blankets and we started playing, and then Link just dropped his guitar, and said ‘Wait a minute, Steve, something is wrong with this sound, it’s horrible!’ He was right. Something was very wrong. What the problem was – the piano was untunable. You could not tune the piano. We had to tune to the piano, so we all were out of tune! That’s how we got that sound. Then other problems came up. Like, the chickens would fly into the coop, through the window. One of the chickens hit me, boom, right in my face. So Fred, Link’s dad, put a chicken wire on the window.

Is it true the album was supposed to be on The Beatles’ label Apple?

We took the tapes to New York to transfer them to eight-track. My wife – now my ex wife – Yvonne, worked for Allen Klein who managed The Beatles and the Stones. One day she went to work and she had forgotten the keys to the apartment so Link and I got a cab to her office to drop off the keys, and by the elevator in the lobby, there was John Lennon. My wife was there with [Lennon’s girlfriend] May Pang, who knew me very well. And she goes: “Hi Steve, Hi Link”, and John Lennon turns around, sees Link, and goes “Link Wray! Man, I love ya!” He hugged him and gave him a big kiss on the cheek. They spent an hour together talking. Then he asked Link, “What you doing in New York, do you live here?” Link says, “No, I’m here finishing my album.” John Lennon was so excited you wouldn’t believe, and he wanted Apple to put out the album, except they could not guarantee me a release within the year. He sent Sid Bernstein – he’s the guy who put The Beatles on their concert tour – to the shack and he wanted John and Link to do a jam together. They wanted to tape it, and they wanted to film it, working at the shack together. But there were problems.

INTERVIEW: ALASTAIR McKAY

The History Of Rock – a brand new monthly magazine from the makers of Uncut – a brand new monthly magazine from the makers of Uncut – is now on sale in the UK. Click here for more details.

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.