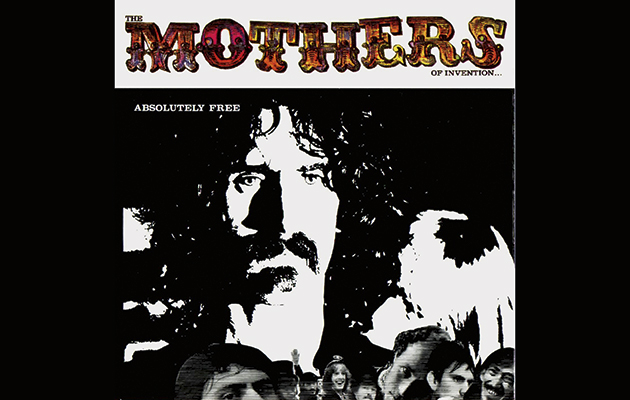

Frank Zappa’s name isn’t featured on the front of 1967’s Absolutely Free, The Mothers Of Invention’s second album. But, as his looming mustachioed face on the cover hints, the disc would serve as the introduction of the real Zappa, for whom the word “iconoclastic” seems to have been invented. Reissued with a rich remastering job, eight bonus tracks and a reprint of Zappa’s mail-order-only libretto, Absolutely Free remains a difficult and ambitious manifesto a half-century later, a sometimes literal overture for the more major works that would follow.

Released in May 1967, at the dawn of the Summer Of Love and a few weeks before Sgt Pepper, Absolutely Free was Zappa’s first crack at freedom in the recording studio. With producer Tom Wilson (Bob Dylan, Velvet Underground) helming the Mothers’ Freak Out! debut, Zappa buried his avant-garde tendencies on the double LP’s second disc. In a drastic tonal shift on Absolutely Free, Zappa puts his classical ambitions upfront, leading with it and never letting up, trading Freak Out!’s pathos-bent R&B for a sound collage of dialogue, “Louie, Louie” references, jazz bursts, and dazzling through-composed interludes.

As the title suggests, Zappa was as interested in the ever-popular ’60s notion of being free as any of his flag-adorned psychedelic contemporaries like the Grateful Dead or the MC5. But instead of interpreting “free” as an excuse for freeform jamming, the drug-free Zappa’s Absolutely Free challenged music’s very structures through rigorously hyper-cut experimental composition. There are vocal hooks and/or choruses on nearly every song, including the opening “Plastic People”, but only as islands in a vaster network of interconnected motifs.

While “Call Any Vegetable” offers the first whiffs of the smirking, scatological themes that would dissuade many listeners from enjoying Frank Zappa’s later music, Absolutely Free is mostly the sound of a young composer at play with the biggest canvas he’s yet been afforded. Expanding the Mothers to include additional horns and a second drummer, “Brown Shoes Don’t Make It” also includes strings and woodwinds, and the entirety of the album’s production and construction obscures the band whose name is displayed in a far larger font than the album’s title.

Attempting to create a critique of freedom itself, Absolutely Free opens by mimicking the sounds of an American news telecast of a presidential address. Continuing themes of “plasticity” from Freak Out!, Zappa set out images he would employ for the next quarter century, his pop smarts confined to tantalising fragments. Unlike Brian Wilson, working across town on Smile, Zappa had no problem compartmentalising his pop inclinations and linking them into a broader tapestry, like the infectious harmony-drenched “Son Of Suzy Creamcheese” (all of 94 seconds) and the chiming “The Duke Regains His Chops” (also under two minutes).

But throughout is the pervading sense that Zappa is cramming too many ideas in, creating a tension with his constant channel changes, resolved only when the Mothers themselves finally appear for an extended stretch on “Invocation & Ritual Dance Of The Young Pumpkin”. On Freak Out!, they’d been not-uncharming purveyors of greasy, underdog LA R&B, a vibe they would continue under the guise of Ruben & The Jets in 1968. On “Young Pumpkin”, they reveal themselves as a dense and thrilling jazz-rock unit with Zappa’s guitar shredding over, under and in collusion with a weaving horn section, anchored by the double drumming of Jimmy Carl Black and Billy Mundi.

Like the pop fragments, the fully operational Mothers would be deployed sparingly on Absolutely Free, and always to good effect, only really stretching out on future albums. While he shifted to session musicians later in his career, the Mothers carried a homegrown mojo as important to Zappa’s early music as Zappa himself. On a contemporary single, included with the bonus tracks, the Mothers find skewed and swinging grooves for both of Zappa’s vague attempts at accessibility on the muscular “Why Don’tcha Do Me Right?” and swinging “Big Leg Emma”. On the album itself, the only song that comes close is “Status Back Baby”, which itself dissolves into a glittering pool of sound midway through. Other bonus tracks include Zappa’s own 1969 remixes of a few tracks and several fourth wall-busting radio ads.

While undoubtedly a massive creative breakthrough, Zappa would articulate his experimental vision and freedom-loving philosophies far more clearly on his next two albums. The equally experimental but more coherent Lumpy Gravy came a few months later, his proper solo debut, while the Beatles-roasting We’re Only In It For The Money turned Zappa’s pop smarts up to the max, including the anti-corporate “Absolutely Free”, and finding an effortless flow of melodies, clever constructions and studio burps, held together by withering but spot-on takedowns of ’60s idealism.

“The present-day composer refuses to die!” Zappa quotes Edgar Varese (from 1921) in Absolutely Free’s liner notes, as he did on Freak Out!. And, in the 21st century, Absolutely Free projects Zappa as just as alive as ever, and just as ornery and obnoxious. Unlike other ’60s artists, whose sounds have long been subsumed into constant revivals, he remains unfashionable enough to be unrepeatable. Absolutely Free’s ideas, arrangements and productions remain ready to challenge any comers over just how free they really are.