Most retrospectives of the late 1960s and early 1970s musical counterculture tend to focus on the gentler side, the pastoral underground that kept the spirit of folk Eden alive. What still remains unfashionably overlooked is the scungier reaction to the hippy idyll: those artists whose refusal to smoke the peace pipe was expressed in a rawer, more desperate form of heavy blues-aftermath rock. Cast as willing outsiders from the start, the likes of Groundhogs, Pink Fairies, and Global Village Trucking Company were slated to play outside the fence, slamming and jamming protests and gurning crudities from the back of a flatbed truck. Mudflecked descendants of Winstanley’s Diggers, arriving in clapped-out vans, to announce the wilting of flower power. Music from a paradise garden turned to mud. The most enduring of these were The Edgar Broughton Band, a righteous, Beefheart-loving brigade formed by Broughton brothers Robert (aka ‘Edgar’) and Steve, with bassist Arthur Grant, in mid-’60s Warwick. With in- again-out-again guitarist Victor Unitt, the outfit delivered a pounding to the Tolkien-tranquilised hordes of UFO and Middle Earth, taking up a strategic position in the Notting Hill scene in ’68, from where they were signed to Blackhill Enterprises and became an early addition to EMI’s ‘alternative’ label, Harvest. This generation of the underground – which effectively lasted until the economic crises of the Heath administration, only to dissipate into the nationwide commune scene and the rugged ordeal of outdoor free festivals – fell into a curious blind spot in UK politics, with general rage against the Man and the Machine, but few specific issues to grapple with. How much more angry energy would’ve been generated had Britain stood shoulder-to-shoulder with the US in Vietnam? As this four-CD set – comprising five LPs plus an unreleased Hyde Park concert from 1970 – reveals, EBB had rage (and humour) in spades. “Death Of An Electric Citizen”, from debut Wasa Wasa, is a Beefheartian romp, as is single “Apache Drop Out”, a curious mix of Safe As Milk boogie and pastiche Shadows. And in channelling their hate into “Out Demons Out!”, the ritual chant of the festival community, taped at a ‘live studio’ concert at Abbey Road in December 1969, they found their vocation. Riffing off The Fugs’ Pentagon-cleansing anthem, “Demons” is goof-off protest folk with a throbbing bluesy vein. Shortly after came the single “Up Yours!”, a V-sign to the political process that today’s student dissenters would be wise to adopt. Sing Brother Sing (1970), full of “songs about child molesters, nymphos and the imminent apocalypse”, according to one review, and The Edgar Broughton Band (1971) were the group’s zenith. Concerts reveal EBB in their element, but surprise subtleties such as the string arrangements and stereo guitar effects on “For Dr Spock” and David Bedfords’s orchestrations on “Evening Over Rooftops” show the group – now back with Unitt – to be more inventive in the studio than their scuzzy image might suggest. “... Rooftops” aspires to epic status, a skyline meditation, uncannily pre-echoing Neil Young’s “Like A Hurricane”, while “The Birth” is lanky and goosey-loose, gritted with hoarse harmonica. For Inside Out (1972), they decamped to a Devonshire mansion. Its remoteness from city life is audible in more laidback, country-ish textures, though “Homes Fit For Heroes” and “Double Agent” still dealt with contemporary issues. Oora (1973) keeps on trucking through triumphalist rock (“Things On My Mind”) and austerity folk-rock (“Eviction”); the end of the Harvest story but not the band, who continue the mission to this day. In this new age of cuts, riots and harsh winters, their music might just start making sense. Rob Young Q+A EDGAR BROUGHTON What are your lasting memories of the Notting Hill scene? I mostly remember the characters and the apparent sense of freedom that pervaded everything. It seemed as if music poured out of every window at times. Why did “Out Demons Out!” need to be written? I was a fan of The Fugs, who presided over a mock exorcism outside the Pentagon USA. We adapted this simple idea to focus the frustration of our audience against the things they despised. Much later it took on a life of its own. More recently, it was an expression of political frustration and also tribal unity. There is a humour present in the recordings that was very much a part of our tongue-in-cheek approach to things. It was fun, and looking back I think it proved to be one of the few occasions when the live Edgar Broughton Band was successfully captured on tape. What have you been up to? I’ve always been involved in political action. This year I’m playing a series of solo shows called ‘A Fair Day’s Pay For A Fair Day’s Work’. I play peoples’ private events for a day of their wages – a practical, socialistic exercise. I have 14 dates booked so far. People can book me directly through my website, edgarbroughton.com. I will be involved with the political action that will grow against this nightmare coalition. INTERVIEW: ROB YOUNG

Most retrospectives of the late 1960s and early 1970s musical counterculture tend to focus on the gentler side, the pastoral underground that kept the spirit of folk Eden alive. What still remains unfashionably overlooked is the scungier reaction to the hippy idyll: those artists whose refusal to smoke the peace pipe was expressed in a rawer, more desperate form of heavy blues-aftermath rock.

Cast as willing outsiders from the start, the likes of Groundhogs, Pink Fairies, and Global Village Trucking Company were slated to play outside the fence, slamming and jamming protests and gurning crudities from the back of a flatbed truck. Mudflecked descendants of Winstanley’s Diggers, arriving in clapped-out vans, to announce the wilting of flower power. Music from a paradise garden turned to mud.

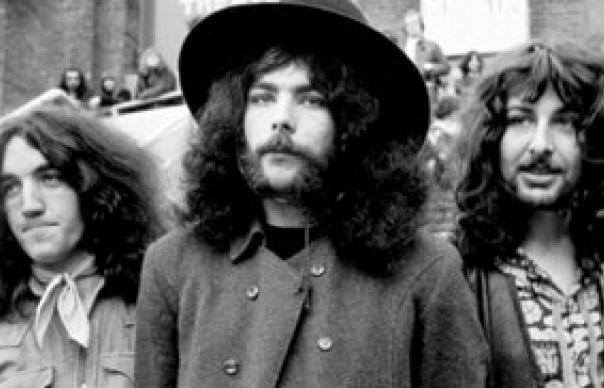

The most enduring of these were The Edgar Broughton Band, a righteous, Beefheart-loving brigade formed by Broughton brothers Robert (aka ‘Edgar’) and Steve, with bassist Arthur Grant, in mid-’60s Warwick. With in- again-out-again guitarist Victor Unitt, the outfit delivered a pounding to the Tolkien-tranquilised hordes of UFO and Middle Earth, taking up a strategic position in the Notting Hill scene in ’68, from where they were signed to Blackhill Enterprises and became an early addition to EMI’s ‘alternative’ label, Harvest.

This generation of the underground – which effectively lasted until the economic crises of the Heath administration, only to dissipate into the nationwide commune scene and the rugged ordeal of outdoor free festivals – fell into a curious blind spot in UK politics, with general rage against the Man and the Machine, but few specific issues to grapple with. How much more angry energy would’ve been generated had Britain stood shoulder-to-shoulder with the US in Vietnam?

As this four-CD set – comprising five LPs plus an unreleased Hyde Park concert from 1970 – reveals, EBB had rage (and humour) in spades. “Death Of An Electric Citizen”, from debut Wasa Wasa, is a Beefheartian romp, as is single “Apache Drop Out”, a curious mix of Safe As Milk boogie and pastiche Shadows. And in channelling their hate into “Out Demons Out!”, the ritual chant of the festival community, taped at a ‘live studio’ concert at Abbey Road in December 1969, they found their vocation. Riffing off The Fugs’ Pentagon-cleansing anthem, “Demons” is goof-off protest folk with a throbbing bluesy vein. Shortly after came the single “Up Yours!”, a V-sign to the political process that today’s student dissenters would be wise to adopt.

Sing Brother Sing (1970), full of “songs about child molesters, nymphos and the imminent apocalypse”, according to one review, and The Edgar Broughton Band (1971) were the group’s zenith. Concerts reveal EBB in their element, but surprise subtleties such as the string arrangements and stereo guitar effects on “For Dr Spock” and David Bedfords’s orchestrations on “Evening Over Rooftops” show the group – now back with Unitt – to be more inventive in the studio than their scuzzy image might suggest. “… Rooftops” aspires to epic status, a skyline meditation, uncannily pre-echoing Neil Young’s “Like A Hurricane”, while “The Birth” is lanky and goosey-loose, gritted with hoarse harmonica.

For Inside Out (1972), they decamped to a Devonshire mansion. Its remoteness from city life is audible in more laidback, country-ish textures, though “Homes Fit For Heroes” and “Double Agent” still dealt with contemporary issues. Oora (1973) keeps on trucking through triumphalist rock (“Things On My Mind”) and austerity folk-rock (“Eviction”); the end of the Harvest story but not the band, who continue the mission to this day. In this new age of cuts, riots and harsh winters, their music might just start making sense.

Rob Young

Q+A EDGAR BROUGHTON

What are your lasting memories of the Notting Hill scene?

I mostly remember the characters and the apparent sense of freedom that pervaded everything. It seemed as if music poured out of every window at times.

Why did “Out Demons Out!” need to be written?

I was a fan of The Fugs, who presided over a mock exorcism outside the Pentagon USA. We adapted this simple idea to focus the frustration of our audience against the things they despised. Much later it took on a life of its own. More recently, it was an expression of political frustration and also tribal unity. There is a humour present in the recordings that was very much a part of our tongue-in-cheek approach to things. It was fun, and looking back I think it proved to be one of the few occasions when the live Edgar Broughton Band was successfully captured on tape.

What have you been up to?

I’ve always been involved in political action. This year I’m playing a series of solo shows called ‘A Fair Day’s Pay For A Fair Day’s Work’. I play peoples’ private events for a day of their wages – a practical, socialistic exercise. I have 14 dates booked so far. People can book me directly through my website, edgarbroughton.com. I will be involved with the political action that will grow against this nightmare coalition.

INTERVIEW: ROB YOUNG