Country music was never the same after the day in 1969 when Kris Kristofferson landed his helicopter in Johnny Cash’s backyard and handed him a demo tape containing “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down”.

Cash recorded the song, and a year later Kristofferson, long-haired, leather-jacketed and with a stoner’s giveaway grin, stumbled onstage at the Grand Ol’ Opry to receive country music’s ‘song of the year’ award. In the grainy footage of the event, you can see the ill-disguised contempt on the face of the tuxedoed host, Tennessee Ernie Ford, as he hands the prestigious prize to someone he evidently regards as a vision of beatnik hell. As Bob Dylan put it, “You can look at Nashville pre-Kris and post-Kris, because he changed everything.”

Dylan, of course, had made his own contribution to nudging country music out of its redneck ghetto when he recorded Nashville Skyline. But he was a rock interloper whose flirtation with country wasn’t going to affect business as usual on Music Row. Kristofferson, on the other hand, was storming the citadel of musical conservatism from the inside and, as the writer Kurt Wolf put it, all the old-timers could do was “wince in displeasure and brace themselves for the invasion”. The outlaws were about to hit town.

At the time Kristofferson was 24, a self-styled “songwriting bum” who was working as a janitor at Columbia’s studios until Cash recorded his song. For a ‘bum’ he had an impressive alpha male CV: Rhodes scholar, college football player, military officer and – as Cash discovered – a qualified helicopter pilot. Everything to which Kristofferson turned his hand seemed to come easy and that included writing evocative songs packed with vivid detail, heartbreaking vernacular poetry and resonant emotional truths which changed the argot of country music.

He was also, as Dylan put it, a “wildcat” and one of the few failures in his life was his attempt to join the dead rock stars club, although he made a valiant effort. “Nothing could kill me,” he said of his rip-roaring, rambunctious early days as a Nashville outlaw. “I was rolling cars and wrecking motorcycles, drinking and doing everything I could to die early. But it didn’t work.”

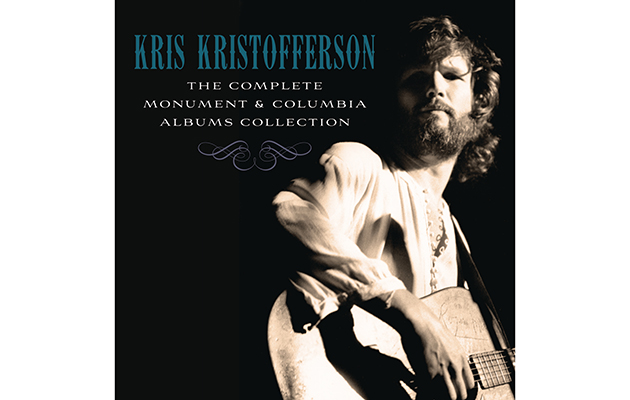

Instead, he went on to create a startlingly original songbook on the 10 studio albums (plus a collection of duets with Rita Coolidge) which he recorded between 1970-81 for Monument Records, the label he shared with Roy Orbison, Dolly Parton and Willie Nelson, and which was subsequently bought out by Columbia, whose studio floor he had swept. The entire run of Monument albums is collected here in a mammoth boxset to celebrate his 80th birthday, augmented with five additional discs of live recordings, demos and out-takes, the bulk of them seeing the light of day for the first time. In total, we get exactly 200 tracks across 16 discs and you couldn’t describe any of them as filler.

The hits are universally known, whether in Kristofferson’s versions or the hundreds of covers. “Me And Bobby McGee“, “For The Good Times”, “Sunday Mornin’ Comin’ Down” and “Help Me Make It Through the Night” all appeared on his 1970 debut, sung in a voice marinated in Jack Daniel’s and sandblasted in grit. When Monument first offered him a recording contract, he told them he couldn’t sing. “Maybe”, they told him. “But you communicate.”

The follow-up, 1971’s The Silver-Tongued Devil & I, contained the title track, “Jody And The Kid” and “Loving Her Was Easier (Than Anything I’ll Ever Do Again)”. 1972’s Border Lord included “Josie” and “Kiss The World Goodbye”. By his fourth album, 1972’s Jesus Was A Capricorn – which included “Why Me”, his biggest hit as a solo recording artist – he was married to Rita Coolidge, whose sultry tones were soon intertwining sensuously with his craggy, pock-marked voice like beauty and the beast on duets such as “It Sure Was (Love)” and “I’ve Got To Have You”.

The story of their marriage was straight out of a classic Kristofferson song. They met on a flight from LA to Memphis and by the time the plane had landed, he had decided not to take his connecting flight to Nashville but to go home with Coolidge. She claimed that before they went to sleep that night they had agreed to marry and had already picked out a name for their first child.

The later Monument albums contained fewer hits as drinking, depression and his movie career increasingly crowded his life. But they’re still packed with searingly honest gems, such as the extraordinary “Star-Spangled Bummer (Whores Die Hard)” from 1974’s Spooky Lady’s Sideshow, “The Fighter” and “Risky Bizness” from 1978’s Easter Island and “The Devil To Pay”, “Daddy’s Song” and “Nobody Loves Anybody Any More”, all of which appeared on 1981’s To The Bone, a stunning, cathartic album recorded in the wake of his divorce from Coolidge and which ranks as his Blood On The Tracks.

The bonus material is generous – an entire disc of unreleased demos of little-known songs; three in-concert discs recorded between 1970-72; and a collection of ‘extras’ that includes four fabulous outtakes from his 1970 debut (among them “The Junkie And The Juicehead Minus Me”, which Cash recorded) plus duets with Joan Baez, Brenda Lee, Dolly Parton and Willie Nelson.

The undated early demos are particularly revealing as the work of a commercial songwriter trying to sell his tunes rather than an artist who intends to records them. They’re expertly crafted to a tried-and-tested Nashville formula: Hank Mills recorded “A Stitch In The Hand”, and it would be easy to imagine Ray Price, Don Williams, Bobby Bare and Kenny Rogers singing “Gypsy Rose And I Don’t Give A Curse”, “I Believe That I Believe”, “The Table, The Glass, The Wine” and “The Hurricane And The Helicopter”. Yet even when commerce rather than art is in the driving seat, the voice of the true poet still shines through.

Given that he never intended to be a performer, the live discs are extraordinary, too: barely a year after he’d been sweeping the studio floor, he’s onstage oozing charisma and firing off irresistible, smart-ass one-liners with virtuosic timing during a masterful set at the 1970 Big Sur Festival.

In an insightful essay in the accompanying booklet, Mikal Gilmore argues that Kristofferson did for country music what Dylan did for the folk tradition. The proof is here in bountiful supply.

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.