Shameless plug coming your way! This Thursday, March 14, the next in our ongoing series of Ultimate Music Guides hits the shops. This one is dedicated to The Smiths. As with previous specials on The Rolling Stones, David Bowie, The Beatles, Bruce Springsteen, Pink Floyd, Paul Weller, Led Zeppelin, John Lennon, The Clash, U2 and The Kinks, The Smiths – The Ultimate Music Guide features brand new reviews of all The Smiths’ albums, plus solo excursions from Morrissey and Johnny Marr, written by a stellar team of Uncut writers, plus a ton of truly mind-blowing classic interviews from the archives of Melody Maker and NME, reprinted for the first time in years. Among them are a few Smiths pieces I wrote for Melody Maker, including a very long interview with Morrissey I did just after the band’s debut album came out, on a wet night in Reading, in the hotel room he was calling home for a night. For the full interview and a lot more brilliant archive content, you’ll need to get hold of the Ultimate Music Guide itself, but here’s an edited version of that original interview I reworked for my Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One Before page in Uncut. Have a great week. Morrissey Reading: February 1984 Later, when he cheers up, we start talking about death and dying, last breaths, the lights going out, the darkness that in the end takes us all. For the moment, though, Morrissey, in a bleak little hotel room in Reading, where tonight The Smiths are playing at the university on a UK tour to promote their just-released debut album, is sitting on his bed, knees tucked up beneath that singular chin, telling me about his troubled teenage years, something we are going to hear a lot about in the months to come, as The Smiths continue their popular ascendancy and everybody wants to know everything about him. When he was 18, he initially remembers, his voice an undulation of moping vowels and world-weary sighs, he wanted only to retreat from the world and its daily grit, lived then on a diet of sleeping pills, incapable at times of even getting out of bed to face the day, lost in barbiturate dreams. It had been a bleak old time, by his detailed account, Dickensian in its gloom and debilitating isolation. “I can’t ever remember deciding that this was the way things should be,” he says. “It just seemed suddenly that the years were passing and I was peering out from behind the bedroom curtains. It was the kind of quite dangerous isolation that’s totally unhealthy. Most of the teenagers that surrounded me, and the things that pleased them and interested them, well, they bored me stiff. It was like saying, ‘Yes, I see that this is what all teenagers are supposed to do, but I don’t want any part of this drudgery.’ “I can see that talking about it might bore people,” he continues. “It’s like saying, ‘Oh, isn’t life terribly tragic. Please pamper me, I’m awfully delicate.’ It’s that kind of boorishness. But to me, it was like living through the most difficult adolescence imaginable. Because this all becomes quite laughable,” he goes on, indulging in a little titter to emphasise the point he’s making. “Because I wasn’t handicapped in a traditional way. I didn’t have any severe physical disability, therefore the whole thing sounds like pompous twaddle. I just about survived it, let’s just say that.” As I was saying a moment ago, The Smiths’ first album’s just out and they’re very much the current centre of attention as far as what used to be Melody Maker and the rest of the weekly music press are concerned. Which is what Morrissey always knew they would be. “I had absolute faith and absolute belief in everything we did, and I really did expect what has happened to us to happen,” he says with quiff-wobbling emphasis. “I was quite frighteningly confident. I knew also that what I had to say could have been construed as boring arrogance. If the music had been weak, I would have felt silly and vulnerable. But since I absolutely believe everything I say about The Smiths, I want to say it as loud as possible.” How long had Morrissey subscribed to the not disagreeable notion that The Smiths were so totally special? “For too long!” he fairly shrieks, making me jump. “And this is why when people come up to me and say, ‘Well, it’s happened dramatically quickly for The Smiths,’ I have to disagree. I feel as if I’ve waited a very long time for this. So it’s really quite boring when people say it’s happened perhaps too quickly, because it hasn’t.” As for what people wrote about him, did he recognise himself in what he read? “Perhaps in a few paragraphs,” he says, a pained expression on his face as he apparently recalled all those column inches, acres of recent newsprint. “But most of it is just peripheral drivel, and a misquote simply floors me. And that happens so much. I sit down almost daily and wonder why it happens at all. But the positive stuff one always wants to believe, and the insults one always wants not to believe. When one reads of this monster of arrogance, one doesn’t want to feel that one is that person. “Because,” he continues, nosing ahead, “in reality, I’m all those very boring things: shy, and retiring. But, simply when one is questioned about the group, one becomes terribly, terribly defensive and almost proud. But, in daily life, I’m almost too retiring for comfort.” So what do you do when you’re not working? “I just live a terribly solitary life, without any human beings involved whatsoever,” he says, apparently resigned to nights in by the fire, a glass of sherry on the mantelpiece, the wireless murmuring in the background, nothing but the weather for company. “And that to me is almost a perfect situation. I don’t know why exactly… I suppose I’m just terribly selfish. Privacy to me is like a life support machine. I hate mounds of people simply bounding into the room and taking over. So, when the work is finished, I just bolt the door and draw the blinds and dive under the bed. “It’s essential to me. One must, I find, in order to work seriously, be detached. It’s quite crucial to be a step away from the throng of daily bores and the throng of mordant daily life.” Are you afraid of relationships, of letting people get too close to you or you to them? “It’s not really fear,” he says by way of considered reply. “I just don’t really have a tremendously strong belief that relationships can work. I’m really quite convinced that they don’t. And if they do, it’s really quite terribly brief and sporadic. It’s just something, really, that I eradicated from my life quite a few years ago, and I saw things more clearly afterwards. “I always found it particularly unenjoyable,” Morrissey says, and he’s talking about sex now. “But that again is something that’s totally associated with my past and the particular views I have. I wouldn’t stand on a box and say, ‘Look, this is the way to do it, break off that relationship at once!’ But, for me, it was the right decision. And it’s one that I stand by and I’m not ashamed of or embarrassed by. It was simply provoked by a series of very blunt and thankfully brief and horrendous experiences that made me decide upon abstaining, and it seemed quite an easy and natural decision.” The week that we meet, the papers have been full of other people’s opinions about The Smiths. What did Morrissey himself have to say about the record? “I am ready,” he says, “to be burned at the stake in total defence of it. It means so much to me that I could never explain, however long you gave me. It becomes almost difficult, and one is just simply swamped in emotion about the whole thing. It’s getting to the point where I almost can’t even talk about it, which many people will see as an absolute blessing. It just seems absolutely perfect to me. For me,” he announces with a flourish that nearly sets the curtains on fire, “it seems to convey exactly what I wanted it to.” _

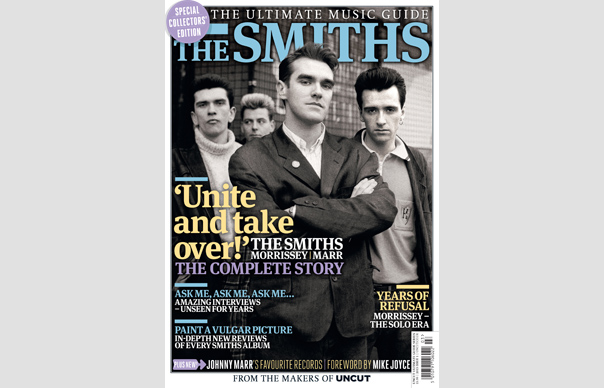

Shameless plug coming your way! This Thursday, March 14, the next in our ongoing series of Ultimate Music Guides hits the shops. This one is dedicated to The Smiths.

As with previous specials on The Rolling Stones, David Bowie, The Beatles, Bruce Springsteen, Pink Floyd, Paul Weller, Led Zeppelin, John Lennon, The Clash, U2 and The Kinks, The Smiths – The Ultimate Music Guide features brand new reviews of all The Smiths’ albums, plus solo excursions from Morrissey and Johnny Marr, written by a stellar team of Uncut writers, plus a ton of truly mind-blowing classic interviews from the archives of Melody Maker and NME, reprinted for the first time in years.

Among them are a few Smiths pieces I wrote for Melody Maker, including a very long interview with Morrissey I did just after the band’s debut album came out, on a wet night in Reading, in the hotel room he was calling home for a night. For the full interview and a lot more brilliant archive content, you’ll need to get hold of the Ultimate Music Guide itself, but here’s an edited version of that original interview I reworked for my Stop Me If You’ve Heard This One Before page in Uncut.

Have a great week.

Morrissey

Reading: February 1984

Later, when he cheers up, we start talking about death and dying, last breaths, the lights going out, the darkness that in the end takes us all. For the moment, though, Morrissey, in a bleak little hotel room in Reading, where tonight The Smiths are playing at the university on a UK tour to promote their just-released debut album, is sitting on his bed, knees tucked up beneath that singular chin, telling me about his troubled teenage years, something we are going to hear a lot about in the months to come, as The Smiths continue their popular ascendancy and everybody wants to know everything about him.

When he was 18, he initially remembers, his voice an undulation of moping vowels and world-weary sighs, he wanted only to retreat from the world and its daily grit, lived then on a diet of sleeping pills, incapable at times of even getting out of bed to face the day, lost in barbiturate dreams. It had been a bleak old time, by his detailed account, Dickensian in its gloom and debilitating isolation.

“I can’t ever remember deciding that this was the way things should be,” he says. “It just seemed suddenly that the years were passing and I was peering out from behind the bedroom curtains. It was the kind of quite dangerous isolation that’s totally unhealthy. Most of the teenagers that surrounded me, and the things that pleased them and interested them, well, they bored me stiff. It was like saying, ‘Yes, I see that this is what all teenagers are supposed to do, but I don’t want any part of this drudgery.’

“I can see that talking about it might bore people,” he continues. “It’s like saying, ‘Oh, isn’t life terribly tragic. Please pamper me, I’m awfully delicate.’ It’s that kind of boorishness. But to me, it was like living through the most difficult adolescence imaginable. Because this all becomes quite laughable,” he goes on, indulging in a little titter to emphasise the point he’s making. “Because I wasn’t handicapped in a traditional way. I didn’t have any severe physical disability, therefore the whole thing sounds like pompous twaddle. I just about survived it, let’s just say that.”

As I was saying a moment ago, The Smiths’ first album’s just out and they’re very much the current centre of attention as far as what used to be Melody Maker and the rest of the weekly music press are concerned. Which is what Morrissey always knew they would be.

“I had absolute faith and absolute belief in everything we did, and I really did expect what has happened to us to happen,” he says with quiff-wobbling emphasis. “I was quite frighteningly confident. I knew also that what I had to say could have been construed as boring arrogance. If the music had been weak, I would have felt silly and vulnerable. But since I absolutely believe everything I say about The Smiths, I want to say it as loud as possible.”

How long had Morrissey subscribed to the not disagreeable notion that The Smiths were so totally special?

“For too long!” he fairly shrieks, making me jump. “And this is why when people come up to me and say, ‘Well, it’s happened dramatically quickly for The Smiths,’ I have to disagree. I feel as if I’ve waited a very long time for this. So it’s really quite boring when people say it’s happened perhaps too quickly, because it hasn’t.”

As for what people wrote about him, did he recognise himself in what he read?

“Perhaps in a few paragraphs,” he says, a pained expression on his face as he apparently recalled all those column inches, acres of recent newsprint. “But most of it is just peripheral drivel, and a misquote simply floors me. And that happens so much. I sit down almost daily and wonder why it happens at all. But the positive stuff one always wants to believe, and the insults one always wants not to believe. When one reads of this monster of arrogance, one doesn’t want to feel that one is that person.

“Because,” he continues, nosing ahead, “in reality, I’m all those very boring things: shy, and retiring. But, simply when one is questioned about the group, one becomes terribly, terribly defensive and almost proud. But, in daily life, I’m almost too retiring for comfort.”

So what do you do when you’re not working?

“I just live a terribly solitary life, without any human beings involved whatsoever,” he says, apparently resigned to nights in by the fire, a glass of sherry on the mantelpiece, the wireless murmuring in the background, nothing but the weather for company. “And that to me is almost a perfect situation. I don’t know why exactly… I suppose I’m just terribly selfish. Privacy to me is like a life support machine. I hate mounds of people simply bounding into the room and taking over. So, when the work is finished, I just bolt the door and draw the blinds and dive under the bed.

“It’s essential to me. One must, I find, in order to work seriously, be detached. It’s quite crucial to be a step away from the throng of daily bores and the throng of mordant daily life.”

Are you afraid of relationships, of letting people get too close to you or you to them?

“It’s not really fear,” he says by way of considered reply. “I just don’t really have a tremendously strong belief that relationships can work. I’m really quite convinced that they don’t. And if they do, it’s really quite terribly brief and sporadic. It’s just something, really, that I eradicated from my life quite a few years ago, and I saw things more clearly afterwards.

“I always found it particularly unenjoyable,” Morrissey says, and he’s talking about sex now. “But that again is something that’s totally associated with my past and the particular views I have. I wouldn’t stand on a box and say, ‘Look, this is the way to do it, break off that relationship at once!’ But, for me, it was the right decision. And it’s one that I stand by and I’m not ashamed of or embarrassed by. It was simply provoked by a series of very blunt and thankfully brief and horrendous experiences that made me decide upon abstaining, and it seemed quite an easy and natural decision.”

The week that we meet, the papers have been full of other people’s opinions about The Smiths. What did Morrissey himself have to say about the record?

“I am ready,” he says, “to be burned at the stake in total defence of it. It means so much to me that I could never explain, however long you gave me. It becomes almost difficult, and one is just simply swamped in emotion about the whole thing. It’s getting to the point where I almost can’t even talk about it, which many people will see as an absolute blessing. It just seems absolutely perfect to me. For me,” he announces with a flourish that nearly sets the curtains on fire, “it seems to convey exactly what I wanted it to.”

_