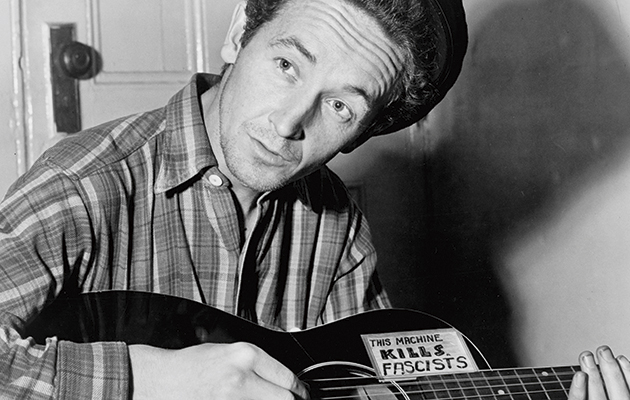

Fifty years after Woody Guthrie’s death, Stephen Deusner examines the life and legacy of a great American hero – from an abandoned plot in Okemah, Oklahoma, to a new generation of protest singers channelling his indefatigable spirit. Originally published in Uncut’s November 2017 issue.

________________________

At the corner of West Beech and South First streets in Okemah, Oklahoma, sits one of the most important empty lots in all of America. It looks fairly anonymous, a rectangle of brittle grass yellowing under the constant prairie sun, sloping gently upwards to a dense thicket of trees and scrubbrush. It’s no different from other empty lots around the country or even just down the street, except for one tree, shorn of branches and bark, long dead but carved with Woody Guthrie’s initials, the name of the town, and the title of his most popular song, THIS LAND IS YOUR LAND. “Five years ago, nobody knew that he wrote ‘This Land Is Your Land’ in New York City,” says his daughter Nora Guthrie. “Most people though he wrote it in Oklahoma, but he wrote it in Bryant Park. A lot of the details of his life were in the dark corners of history until recently, and they’re still coming out into the light.”

Folk music may not be the populist medium it was during Woody’s lifetime, but he remains an important figure in 2017, partly as he seems to be revealing new facets of himself everyday.

“He was so much bigger than a folk singer,” says Anna Canoni, his granddaughter. “He was bigger than any genre. He only recorded about 300 songs, but he wrote more than 3,000. So there’s still a lot of stuff out there. It’s a joyous responsibility to share all of this information with people.”

There in Okemah, just underneath that carved tree, is the site of the Guthrie homestead, where Woodrow Wilson Guthrie, born in 1912, spent much of his childhood. A fire took the family’s first home, a larger, newer dwelling in a better neighbourhood, and they moved here to what they called the old London House after its previous occupants. According to Guthrie, the family hated the place, but he didn’t know enough to despise it just yet. In his 1943 memoir Bound For Glory, which is so heavily fictionalised it’s often called an autobiographical novel, he writes: “I liked the high porch along the top storey, for it was the highest porch in all of the whole town… [You could] see the white strings of new cotton bales and a whole lot of men and women and kids riding into town on wagons piled double-sideboard-full of cotton, driving under the funny shed at the gin, driving back home again on loads of cotton seed.”

He reminisces about getting stuck up in an old walnut tree, perhaps the same one that bears his name today; he also recalls a “cyclome” shearing the roof right off. The Guthries moved once again, their fortunes and luck dwindling. Woody grew up, got married, travelled the country, served in the military, wrote thousands of songs, sang in the Almanac Singers with Pete Seeger, and died in 1967.

The London House sat empty for decades after the Guthries abandoned it. In the 1970s a businessman named Earl Walker purchased the lot and intended to turn the house into a museum. Already the local boy was considered an icon of American music – he was by far the most famous native of Okemah, yet the town resisted his canonisation, purportedly due to his Communist leanings. Guthrie was never a registered member of the Communist Party, in fact, he was rarely a registered member of any organisation, suspicious as he was of infringements on his freedom. He did make his name playing Communist Party rallies in the ’30s, but he seems to have finally settled in as a pro-union Socialist with progressive, albeit occasionally contradictory views on race and class. Many of those beliefs, Guthrie argued, were rooted in his experiences in Okemah, an agricultural town that transformed first into an oil boomtown and later into a ghost town. The region’s fortunes were echoed in the London House, which became a target for vandals and fans who took bricks and wooden planks as souvenirs.

Today there is nothing to officially mark the vacant lot as a historical site. Even that carved tree, a piece of folk art in its own right, isn’t an official installation, but something carved by a local fan. Perhaps that’s fitting, since Woody was an avowed populist, a champion of the common man against the encroachments of corporations and crooked politicians. Okemah finally did commemorate him with an annual folk festival, a small park, and a replica of the London House at the Okfuskee County History Center, but this vacant patch of grass might be a bit more in keeping with Woody, who made himself the subject of tall tales and the occasional outright lie, who penned Dust Bowl ballads based on newspaper headlines, who camped with migrant labourers and rode the rails with itinerants of every stripe, who spent his final decades in a hospital in New York, where Huntington’s chorea took his motor skills, his speech, his mobility, his mind and, in 1967, finally his life. Fifty years on, public memorials and statues are at the heart of an extremely heated discussion of how American remembers its history and how it uses its common spaces. This vacant patch of grass is strangely compelling, even moving in its modesty, in the homemade quality of its commemoration. This empty lot is your empty lot, this empty lot is my empty lot.