John Fogerty’s show supporting Bruce Springsteen at London’s Hyde Park is reviewed in the new issue of Uncut, out now (dated September 2012). So, for this week’s archive feature, we delve back to March 2006 (Take 106), when the Creedence singer, guitarist and songwriter talked Uncut through all of his legendary band’s singles. Interview: Bud Scoppa

__________________________

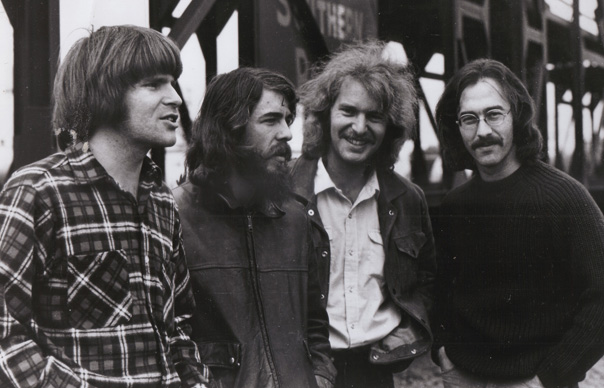

It was a rags-to-riches story in flannel. At the tail end of rock’s most vital period, Creedence Clearwater Revival, a group of modestly talented musicians on an obscure label, came out of nowhere to become the biggest band in the world.

Between late 1968 and 1970, CCR virtually owned the US Billboard Top 40, and in 1969 they officially displaced The Beatles as the biggest band on the planet, selling more records over those 12 months than any other act around. That same year, they played Woodstock and, although they declined to be included in the film, they were allegedly the second highest-paid act on the bill after Hendrix. Nor was their success confined to America. In 1971, Creedence succeeded The Beatles as top group in the annual NME poll.

The passing decades have obscured the near miracle pulled off by John Fogerty, his brother Tom, Doug Clifford and Stu Cook, but it really happened, and I watched it unfold, mesmerised by the band from the first time I heard their reinvention of Dale Hawkins’ ’50s classic “Susie Q” on the car radio during the summer of 1968. When I saw Creedence headline Madison Square Garden in 1970, right at the peak of their popularity, the sellout crowd was just as adoring as the one that had come to worship The Rolling Stones in the same arena a few months earlier. But unlike the exotic and dangerous Stones, Creedence were a people’s band – make that the people’s band, their perceived populism at the heart of their appeal.

Hailing from the Bay Area, they cranked out six albums in just over two years, and also racked up 20 singles in the US Top 20, including standards like “Proud Mary”, “Bad Moon Rising”, “Green River”, “Fortunate Son” and “Who’ll Stop The Rain?”.

Their name was the creation of the younger Fogerty brother, John, as were the songs, arrangements and production. He was a middle-class kid from El Cerrito, California who transported himself to the bayou country of the Deep South in his imagination, doing so in the very shadow of – and in polar opposition to – psychedelic kingpins The Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane across the bay.

John was an autocrat who got consistent results through what he now describes as “maniacal control”. Eventually his bandmates rebelled, demanding democracy. This change of operation resulted in Creedence’s swan song, 1972’s Mardi Gras, widely considered to be the worst album ever released by a major artist during the rock era. So the CCR saga, which began as a real-life variation on Rocky, ended up more like This Is Spinal Tap.

I spoke with John Fogerty for the first time in 1970, just after a sell-out Creedence show at Madison Square Garden. He emanated a confidence bordering on arrogance, coming off less like a rocker than a hard-nosed businessman. On that score, the years haven’t mellowed him. Meeting Fogerty in December 2005, he carries within himself an unabated rage at longtime Fantasy Records owner Saul Zaentz, to whom Fogerty naïvely signed over his valuable catalogue of beloved songs.

When Zaentz recently sold Fantasy to the Concord Music Group, Fogerty jumped at the chance to re-sign with his old label, with whom he put together the career retrospective The Long Road Home. But the fact that he’s once again in close proximity to his catalogue also fuels his frustration at not owning what he created. Additionally, he remains bitter towards his former bandmates (Cook and Clifford continue to tour as the core of Creedence Clearwater Revisited, performing the Creedence hits) for what he sees as their unwillingness to acknowledge his central role in the band – and for siding with Zaentz against him. For the same reasons, he never reconciled with brother Tom, who died in 1990.

But, before the acrimony, there were years of closeness as the band struggled for acceptance, eventually gaining it beyond their wildest dreams. They’d come together as The Blue Velvets way back in 1959. When the British Invasion changed everything, they became The Golliwogs, scoring a modest local hit in 1966. Fogerty renamed the band Creedence Clearwater Revival in late 1967, a few months after writing the song that set the template for the band’s unmistakable sound during his six months of active duty in the US Army Reserve. The Creedence auteur picks up the story at this point, and takes us through his ride on the rock rollercoaster by looking back at a string of indelible hits that captured the mood of the times like no other.

_____________________________

PORTERVILLE

Released: January 1968 (didn’t chart)

From: Creedence Clearwater Revival (July 1968)

Fogerty: I went into the army in early ’67, and they got you marching all day out on an asphalt parade field about a mile square. And during all that marching, I would get delirious, and my mind would start playing little stories. They all seemed to be sort of swampy and Southern, in the woods and with snakes; Br’er Rabbit, Mark Twain, a great old movie with Dana Andrews and Walter Brennan called Swamp Water. So I ended up writing the song “Porterville” while I’m stomping around in the sun. It’s semi-autobiographical; I touch on my father, but it’s a flight of fantasy, too. And I knew when I was doing it, ‘Man, I’m on to something here.’ Everything changed after that. I gave up trying to write sappy love songs about stuff I didn’t know anything about, and I started inventing stories.

SUZIE Q

Released: August 1968 (peak US chart position 11)

From: Creedence Clearwater Revival

At the time, there were a lot of songs – by the Dead, the Airplane – where it got very boring for many, many minutes. If we’re gonna have some 15-minute jam, I’d rather hear some guys that can really play, if you know what I mean. So, since the guys in Creedence were not world-class musicians, I would arrange the song so that it kept movement going. Having that structure, but at the same time having these people that were obviously kids in this charming, unpretentious little band, it made for some intimate or vulnerable-sounding music. Once I got to the point where I understood that the arranger in the band was far ahead of the musicians in the band, it just snapped into shape. Three months before we recorded “Suzie Q”, we sounded like your average, low-on-the-totem-pole bar band – which is what we were. I just kind of grabbed the reins, and it shaped up our ragtag little band into something that sounded pretty good very quickly. We weren’t whizz-bang, world-class virtuosos, and our strength was in the groove we could create together.

“Suzie Q” was far out – kinda startling for that time. So Saul [Zaentz], in his wisdom, said, “Maybe I should have you guys record an album.” So we did some of the cover songs that we’d been doing, like [the Wilson Pickett hit] “Ninety-Nine And A Half” and [Screamin’ Jay Hawkins’] “I Put A Spell On You”. So then I was off and running as producer/arranger. It’s remarkable that a 23-year-old was now the producer of what was about to be the world’s biggest band. I got to run the show because there was nobody at Fantasy that had a clue. When “Suzie Q” hit, there were two people at the label, and I had recently been one of them – I was a shipping clerk in ’65 and ’66.

Also from Creedence Clearwater Revival: “I Put A Spell On You” b/w “Walking On The Water” (October 1968; peak US chart position 58).

PROUD MARY b/w BORN ON THE BAYOU

Released: January 1969 (peak US chart position 2)

From: Bayou Country (February 1969)

The first album came out on my 23rd birthday, May 28, 1968, and we were off and running as Creedence, but still kind of a second-on-the-bill act. But all through that time, I’m writing very busily. This was where all that evolution very dramatically occurred in me. I’ve seen science-fiction movies where the guy’s head suddenly doubles in size; that’s actually what occurred to me. All that stuff – all that imagery, that Southern lore, all that fable stuff that’s in the songwriting, starting with the name and the plaid shirt – was going on in me, and the other guys were still the bar band.

Bayou Country really stated what Creedence Clearwater Revival was and should be. There were hints of it on the first album. The singin’ is good, and the band plays well; it just doesn’t sound as authentic as Stax. But Bayou Country just lands very authoritatively. The title track, with that droning chord and that whole spooky thing, that’s such a great opening. And the cover shot, which was just by accident, was spooky and undefined, and it did nothing to dispel the vision.

Because I was writing – this is late ’67 and early ’68 – it occurred to me one day that what I liked was song titles. So I went down to the drugstore in El Cerrito at the mall, and I went and got myself a cheap little notebook, and I made myself a title page that said “Song Titles” [laughs], and the first thing I wrote was “Proud Mary”. I looked at it and said, “Hmm… what does that mean? Maybe it’s like a domestic worker, a maid.”

Then I began to write some melody. The flow sounded good, but I had no idea what it was about. So I go back to the song-title book and “Proud Mary” is sittin’ there, and dang if it didn’t sound like a paddle wheel goin’ around. I said, “Man, that sounds like a riverboat!” Now, that’s the magic, the myth, the voodoo of this whole deal. I began to write the song – the story – of that boat, Proud Mary. It was the central character. That’s exactly how it happened; it’s no more mythical than that.

We went into RCA in Hollywood, Studio A, to record Bayou Country in October [1968]. We had the music for “Proud Mary” recorded, and I knew what I wanted the backgrounds to sound like. I showed the other guys how to sing the backgrounds, having remembered what we’d sounded like on “Porterville”, which was very ragged, not melodious, and I had this beautiful harmony sound in my head, kinda like what the old gospel groups would do. And I heard our tape back, and I just went, “Nahhh, that’s not gonna work.” So we had a big fight over that. I said, “I’m gonna sing all the parts” – ’cause I’d been doin’ that for years with my tape recorder at home, and I knew harmony, and the other guys, frankly, did not. We literally coulda broke up right there.

I was well aware of the sophomore jinx; I did not want to go back to the car wash. I actually made that speech: “If the second one stinks, we’re a one-hit wonder.” Instead of delving into the underground, my Elvis-and-Beatles upbringing came directly into play. And I was able to write songs that would go on Top 40 radio, because that’s what I had wanted to do since I was four. I wanted to make hit singles; I thought that was my job. At the conclusion of “Proud Mary”, I even said to myself, “Wow, that’s my first standard.”

BAD MOON RISING b/w LODI

Released: April 1969 (peak US chart position 2)

From: Green River (September 1969)

“Proud Mary” and Bayou Country were in the US Top 10 by February [1969], so I knew we needed another single. It was in my mind, at least, to compete with The Beatles.

I had the phrase “Bad Moon Rising” written down in my song-title book. I thought back from that to an old movie I’d seen called The Devil And Daniel Webster [1941]. It’s about this man who sells his soul to the devil to have greater rewards here in this life, and one night there was this terrible hurricane, and the man is cowering in his barn. In the morning, he looks over at his neighbour’s yard, and all the corn is just squashed down, and everything’s totally destroyed. And, right at the fence line, where his property is, the corn is standing straight up, peaceful and untouched. That just seemed so spooky, the idea of an epochal force –nature, or the devil, or whatever – that’s gonna get you.

Later, people began to point out, “Hey, John, you’ve got this song about death and doom, but it’s this bouncy little thing.” And I’d go, “I just didn’t worry about that part.” The scariness of the words seemed to be telling enough; the cool music was gonna put it across. When you’re a very tuned-in young person, you’re tied to everything that affects your generation. So I think [that some social commentary] was in there…

On “Lodi”, I saw a much older person than I was, ’cause it is sort of a tragic telling. A guy is stuck in a place where people really don’t appreciate him. Since I was at the beginning of a good career, I was hoping that that wouldn’t happen to me.

GREEN RIVER b/w COMMOTION

Released: July 1969 (peak US chart position 2)

From: Green River

After Bayou Country, I began to feel I had the freedom or power to do what I wanted. And where I went, starting with “Bad Moon Rising”, was right to my emotional, musical core, which was very resonant of Sun Records. “Green River” was my favourite song from the Creedence era, because it really had the whole Sun Records vibe to me – and the album, too. The barefoot boy with a cane pole down by the river – it seemed to have that feel all over that album. My own personality really came to the fore. When I was 7, 8 years old, I started collecting titles, and “Green River” came from sitting at the counter at the drugstore a block-and-a-half from my house in El Cerrito. They served soft drinks, and behind the counter was a big bottle of Green River, which was a syrup. On the label there was this artist’s rendering of a sunset behind a little creek. I said, “‘Green River’… that’d be a cool song. Someday I should grow up and write it.”

“Green River” was a true place. It just seemed very Southern in nature, although it happened to be a place in Northern California. It was where my parents took the family on summer vacation, a two-room cabin. The creek, Putah Creek, was no more than 15 or 20 feet from the back door, and there was a rope hangin’ from the tree. I discovered pollywogs the first time I went underwater. It was quite a strong memory. Here, nearly 60 years later, it’s still quite a strong memory of… I don’t know… discovery, independence.

I didn’t think “Commotion” was social commentary, ’cause all this stuff was just in the air. I realised it wasn’t “Blue Suede Shoes”, but, trust me, if I could’ve written “Blue Suede Shoes”, I would’ve sold my soul for it. But I was writing about what was in the air, and that was what came out of me. I was just doing what came naturally.

DOWN ON THE CORNER b/w FORTUNATE SON

Released: October 1969 (peak US chart position 3)

From: Willy And The Poorboys (December 1969)

“Fortunate Son” is a very powerful anti-war message, but even more so, it’s an anti-class-bias message. The injustice of having a few ruling a working class, or middle class, of many, who are actually doing all the work and creating all that wealth. When I sing it now, it still says it as well as I could ever want to say it. It’s not just some old song that I sing; it still has teeth. I daresay it’s one of the better examples of that genre to come out of the ’60s. And it’s still applicable right now. Our president [George W Bush] is probably the most fortunate of all fortunate sons.

“Down On The Corner” is just a good song. In 95 per cent of my shows, when we get to “Down On The Corner”, the entire audience is as one. It’s the one that really transcends.

TRAVELIN’ BAND b/w WHO’LL STOP THE RAIN?

Released: January 1970 (peak US chart position 2)

From: Cosmo’s Factory (July 1970)

“Travelin’ Band” was my salute to Little Richard, but “Who’ll Stop The Rain?” was part of the fabric of the times. From ’68 to ’74, Vietnam was probably the most important thing on the minds of young people. So there was the dichotomy of old people saying one thing and young people feeling quite another thing and therefore not trusting old people, starting with the government, Richard Nixon, and his position on the war. Nixon would say this baloney… By the way, this morning, on CNN, you could watch George W Bush doing the same thing… Anyway, rain being an elemental and inescapable reality, that was the context into which I was putting all this baloney.

UP AROUND THE BEND b/w RUN THROUGH THE JUNGLE

Released: April 1970 (peak US chart position 4)

From: Cosmo’s Factory

I put a little music room in my house in late ’69, and I was up there with a guitar, fiddling around with a lick from [Marty Robbins’] “White Sport Coat (And A Pink Carnation)”. Later, I was out on my motorcycle riding around Berkeley, probably going around a corner. It had this sense of urgency. So when I got home, I went up to that room and married the urgency of going somewhere to that riff. And I made a whole song out of, ‘We don’t know where we’re going, but we’re on our way.’ Y’know, the way all kids feel – just immortal.

The band was scheduled to go to Europe in March 1970. But I didn’t have those two songs finished. I had already scheduled time at a studio for the next week, so that weekend I had to come up with the two songs. That Monday morning, I said to myself, “You’re a songwriter.” I had done what to me was impossible, which was, with a gun pointed to my temple, I’d finished those two songs. So I got ’em recorded, then left for Europe.

Also from Cosmo’s Factory: “Lookin’ Out My Back Door” b/w “Long As I Can See The Light” (August 1970, peak US chart position 2)

HAVE YOU EVER SEEN THE RAIN? b/w HEY TONIGHT

Released: January 1971 (peak US chart position 8)

From: Pendulum (December 1970)

When we first signed with Fantasy, Saul had promised that if there was ever success, we’d get a “bigger piece of the pie”. And all of us that were family [laughs] – I mean band members – remembered that. So it was decided I should go talk to Saul. Saul slammed the door in my face. We were supremely unhappy after that.

Just before Pendulum was gonna be recorded, the other three guys called a meeting, and they insisted on a democracy – that everybody could write songs and sing, and everybody would have a vote. From the background voices of “Proud Mary”, I had managed to keep that thing under control, but I couldn’t any more. We recorded Pendulum under that cloud, and the song “Have You Ever Seen The Rain?” is basically describing that. Here we have a beautiful, wonderful sunny day that we’ve all been striving for, and now there’s this big black cloud raining down on it.

I’d been on such a roll. Then I remember thinking, ‘My head hurts. I feel like my brain tissue is dry, like it’s dehydrated or something.’ What I was feeling was just stress. I felt so put-upon to make music while all this crap was goin’ on. I somehow came up with “Hey Tonight” in the middle of it all, but also a couple of duds. I was not able to function properly because of all the controversy. After Pendulum, the other guys hired a press agent, who arranged a huge party, and the other members chose this moment to describe their newfound freedom. “We’re out from under John’s tyranny,” was one of the quotes. I ended up calling this event The Night Of The Generals, because everybody was now a general; there were no more soldiers. It was a train wreck, and within two weeks, Tom left the band. There was no goin’ back after that. I said at one point, “I run this band on nerves and willpower,” because there was always this whole litany of jealousy and crap. It was like, ‘God, we’re No 1 band in the world – isn’t this good enough?’

The major break-up point was the other guys wanted to write songs. I finally caved in. But I knew it was the end of the band. ’Cause they wanted to write their very first song in the world’s No 1 rock band. It’s ludicrous. But even now, I look back at how much stuff was done from May of ’68 until the end of 1970. And the other guys at some points were my willing students, and at others my rebellious bandmates. That’s the journey we lived through. And while they were willing students, it was fun.

Two of Fogerty’s three contributions to CCR’s last album, Mardi Gras (April 1972), were released as singles: “Sweet Hitchhiker” (July 1971, peak US chart position 8), and “Someday Never Comes” (April 1972, peak US chart position 25). The band formally split up on October 16, 1972.