Originally published in Uncut's July 2020 issue

Originally published in Uncut’s July 2020 issue

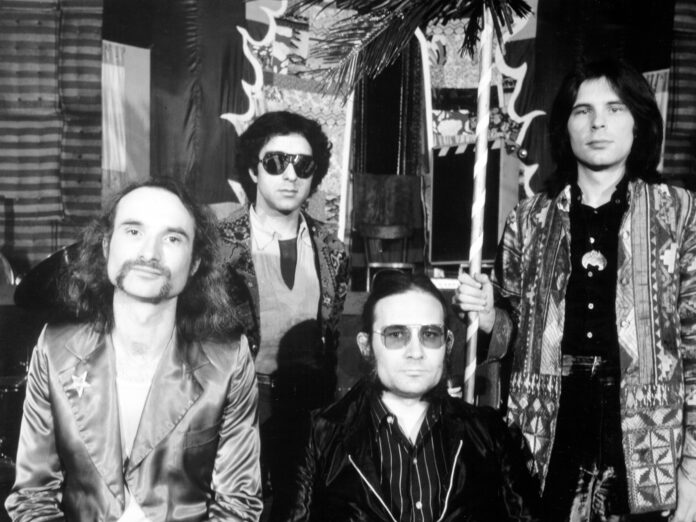

Irmin Schmidt pushes pause on his forward-looking endeavours to reflect on 60 years as a true innovator. To discuss: fallen comrades, “evil” jazz and magic. “Music is an adventure every time,” he tells Tom Pinnock

NEIL YOUNG IS ON THE COVER OF THE NEW UNCUT – HAVE A COPY SENT STRAIGHT TO YOUR HOME

With a screwdriver in his hand and assorted screws between his teeth, Irmin Schmidt is deep in concentration. He’s remodelling the piano in Huddersfield’s St Paul’s Concert Hall by “preparing” it – inserting all manner of items between its strings. It is a method invented by John Cage that Schmidt intends to use during a concert he is playing here later tonight. Adjusting a piece of felt by a minute amount, he strikes a key, producing a muffled, bittersweet tone.

“That’s very Debussy,” he says, breaking into a smile. “I will remember that and use it tonight.”

Prepared piano, backed by manipulated field recordings, might be very different from the pulsing rhythmic inventiveness of Can, but Schmidt

is still following the questing route dug by the visionary group that he formed in Cologne in 1968. Looking back at performances from throughout his long career – in Can, as a solo artist or otherwise – he considers their improvisatory nature essential to his way of doing things.

“If you take the risk to go on stage without knowing what you are going to play, then of course a lot is going to go wrong,” he says. “But if it succeeds, then it’s very good.”

Now in his eighties, Schmidt has travelled from his home in the South of France to perform in this converted church for one of Europe’s most revered experimental festivals. His first album of prepared piano, 5 Klavierstücke, came out in 2018 – but here he’ll be performing brand new pieces, still based around prepared piano and manipulated field recordings. The results, recorded live by Can’s long-time sound engineer René Tinner, comprise a new album, Nocturne, released on Schmidt’s 83rd birthday: May 29.

“It looks quite relaxed when I’m doing this,” says Schmidt, resting in a hotel bar once the piano wrangling ceases after four-and-a-half hours. “But it’s work that requires a lot of concentration. Everything you do – the overtones, the colours – they have to interact. It’s like creating a new kind of instrument.”

This year marks 50 years since Damo Suzuki joined Can on vocals, completing their most acclaimed lineup, resulting in albums such as 1971’s Tago Mago and the following year’s Ege Bamyasi. “Every second

year I have a kind of jubilee,” says Schmidt of the anniversary, wryly. “Sixty years married, all kinds…”

Yet he remains a keen custodian of the band’s work, especially now that he’s the only surviving member of the core quartet that anchored the group throughout their long career; drummer Jaki Liebezeit and bassist/tape artist Holger Czukay both passed away in 2017, while guitarist Michael Karoli died in 2001, aged just 53. “It’s hard almost to talk about them not being around any more,” says Schmidt, “because they were some of the people I’ve been closest to in my life, especially Michael. But Jaki too… I got really sick coming back from his funeral without knowing why. I miss them. They were the most important musicians in my life.”

The keyboardist is currently working on restoring and releasing a set of Can’s live recordings, including full improvised sets and possibly radio sessions, and he and Tinney reveal some of its treasures to Uncut. Schmidt also finds time to tell us about Hendrix, Beefheart and Stravinsky, recall how he made his musical mentor cry with some “evil” jazz, and muse on other, more esoteric matters.

“Well, any good music,” he says, eyes twinkling behind his spectacles, “is magic.”

UNCUT: Being the last remaining member of the core four in Can, does it put more pressure on you to look after the work?

SCHMIDT: It’s no pressure – in fact, it’s precious! It’s an obligation, maybe, but I feel quite OK with that. It’s a good obligation, definitely.

You have some Can archival live releases on the way, which is very exciting news. What can we expect to hear?

Spoon is planning with Mute to release a series of live records that were never released before. Parts of them were on obscure bootlegs. Andy Hall, a fan of ours, collected whatever he could get hold of in the ’70s, and he recorded quite a lot too. Even if the quality of the recordings is not so good, there are now possibilities to improve it in the mastering. Especially in the UK, people knew us from live performances much more than they knew us from records – our performances made part of our fame. Documentation of our live appearances is missing from our releases, so I’m quite happy that this gap will be filled.

So how much stuff is going to come out?

I don’t know yet. We have four concerts at least. I don’t want to have single pieces from hundreds of concerts, because the real impression of how it

was is if you hear, say, an hour and a half of one session, because then there is this dramaturgy, this architecture, of making an hour’s music as

one thing, which we sometimes succeeded to do. Sometimes it was totally different from anything we had done before, sometimes we would quote our existing songs.

Do these concerts come from different periods of Can?

The best I found were between 1974 and ’75, when it was only us four, without any singer, after Damo had left. Then there are some radio sessions too, funny ones, with Damo.

Was it freeing, that period when it was just the four of you?

We found out that singing isn’t that important. There are some wonderful things with Damo, but they were very badly recorded. It was really an endeavour. Our concerts were normally two sets with an intermission in between and every set was at least an hour, sometimes an hour and a half. So on what we’ll release there will at least be a total of one set of a concert, so you can hear how we build it up, come down and go back. Because they have a real architecture, these sets, the good ones.

Considering your background as a respected classical musician and conductor, contacting Holger Czukay and forming Can in 1968 seems a very brave idea…

For me, it’s less brave than totally natural. All these changes I have made – from classical and Fluxus and classical contemporary to Can and then from Can to writing an opera, Gormenghast, and now doing this – I don’t see a difference for me. It’s all contemporary music: I don’t differentiate between classical, art and pop music. It’s my kind of art and I have to express it, and from time to time change the way I am expressing myself. But it’s still my emotions, my memory, my art. Of course, it’s an adventure every time, but without that element it wouldn’t be important to do it.

Talking of new adventures, what’s different about these latest pieces?

They are totally different to Klavierstücke, absolutely different. They’re both very much based on the field recordings that accompany them, but on Klavierstücke it was a little lake and reeds – now it’s not sounds from nature at all! It’s also quite a different style, because whenever you open up a new field like I did with Klavierstücke, which was something totally new in

my work, then you start again from the beginning. Everything you have to say, you can say it again in a totally new and different way.

You’ve played prepared piano previously…

Yes, about 60 years ago! There were these compositions for prepared piano by John Cage, which did very much interest me because it was something totally new. It was his invention, more or less. Then I met him and discussed it, so I performed a lot of Cage. With these new pieces, I’m not using chance like he did, even if the pieces are invented in the moment; it’s more like composing instantly, like it always was with Can. With Klavierstücke and Nocturne, there is no editing. It’s a kind of zen thing. It’s like these Japanese painters, who for years might meditate about a branch of bamboo with a bird on it, and then one day in 20 seconds – whoosh, whoosh, whoosh – they paint it and it’s perfect. There has to be presence of mind, and when it succeeds you really catch the moment, when inside and outside is one thing.

It’s interesting that there was no editing – in Can you were generally using the same process of improvisation, but it was hours of music that was then edited down.

Yeah, I don’t do that any more. I wouldn’t play hours and hours and then edit it together. Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but it’s passed. At my age, you have a different relation to time. First of all, there is a lot of time you’ve spent already, and secondly, there isn’t much time left. Now if it doesn’t succeed, you throw it away.

Do you remember how you first became interested in music?

In the war, when we lived in Berlin, we were always listening to the radio, but after that we were bombed out and lost everything. We moved to a remote place in the Austrian Alps and we had no radio. The only music I heard was when people sang. But when we came back to Germany we had a radio, and I would listen to classical, romantic and 19th-century music. Then when I was 14, I heard The Rite Of Spring by Stravinsky. That was my introduction to 20th-century music. It’s such a wonderful work.

Then your horizons opened up to more avant-garde sounds, and jazz?

The Nazis had practically totally forbidden jazz, and that carried on long into the ’50s. For instance, when I was 16, 17 or 18, my English teacher, who played organ in a church, liked me very much because I made a lot of music and I had founded a school orchestra. He finally succeeded in getting the money together to build a beautiful big organ in our school hall. I was the only pupil who was allowed to play on it, because he loved me. One day, I organised the first school jazz concert ever in that part of Germany. This guy was crying, because it was sacrilege to do that to the organ. Jazz for him was sin, it was something evil.

I guess that made you like it even more?

[Laughs] I had already started to like it, but I never played it. But I listened to it relatively early for the time and collected records – that was considered something very suspicious. Culture was in ruins, like the towns. It was not only the material world that was destroyed in the war.

Can you recall a particular moment when you realised that rock and pop could be as interesting as jazz or classical music?

It was of course in the ’60s, especially when Jimi Hendrix appeared. But also others – Captain Beefheart very much. I grew up with 600 years of European classical music, that was my musical world, and Jimi Hendrix easily integrated into that. We live now in such an incredibly rich musical environment: we can listen to Polynesian music, gamelan, we can listen to all kinds of African music or to ancient Japanese music – and I do. It’s no longer discovering something strange and far away, it’s part of the globalisation that we live in. It’s a pity we can’t listen to music like the old Egyptians made in the way that we can see their art or read their writing on stone. But in a way, all music is contemporary music now. It’s there, and if you want to, you can really dive into it.

The way you approached music back then, in this cross-disciplinary way, is the way many people approach music now. But it must have been a lot rarer in the ’60s?

Of course. Even in pop music, there were straight categories, and there are still. There were rules on how to write a song, how the structure had to be. And all these rules don’t interest me. Never did.

Have you ever written a song in the traditional way?

Yeah, of course! I mean, there are Can songs that have a kind of straight structure, and there are songs on my solo records, like “Weekend”, which have very conventional structures. But neither Can nor my own work is pop. It’s a kind of contemporary art music. What I’m doing musically now sometimes has more to do with contemporary painting – someone like Cy Twombly is nearer to what I’m doing at the moment than any other music.

Klavierstücke was recorded at your home studio. What’s a normal day like for you in rural France?

I have a piano in my bedroom and one in the studio, and the studio is also a library with maybe 3,000 books. They are good for the acoustics! I read a lot; it’s one of my favourite occupations. Sometimes I take a walk through the valley, or I have a swim in summer daily. I have to make sure there is enough wood for the fireplace or do the shopping. I cook a lot, too. And I spend a lot of time in the studio. Whatever I do, René is always doing sound engineering – ever since he came to Can in ’73, we have worked together. I spent some weeks with René recently listening to hours and hours of live tapes. Sometimes I just sit at the piano and play.

I’ve heard about a more esoteric side to you, talk of magic back in the Can days. Do you still dabble?

At the time it was nice to talk about that, but the time has gone. But

it can happen that on a midsummer night I’m sitting on the terrace listening to the silence of the valley, and it’s totally magic – it has nothing to do with any kind of esoteric blah-blah, but you can call it magic. It’s absolutely wonderful and it’s rich and you can dive into the silence. It’s the same with music – that can be magic, can’t it?

Yeah, and the music you’ve made still casts a spell – it seems like Can especially are more popular than ever now.

Yes. That’s what I meant by contemporary art music. It’s not pop in the sense of fashion. What we did was really trying to nail down the moment – if you are lucky, it can last. If you write a book, it could be something nice and entertaining, but five years later it has no interest any more. Obviously, that’s not the case with what we did. Can’s music tells something about the historical moment, and it even tells it very precisely; but it’s consistent, so it can last.