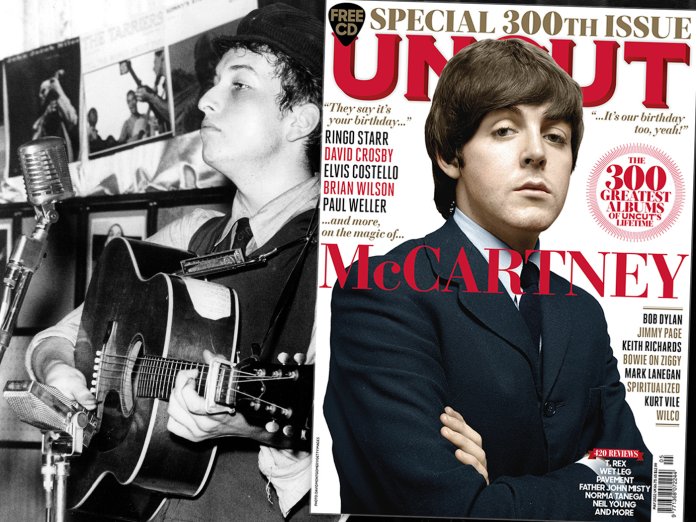

Bob Dylan had a joke he wanted to tell the crowd at Gerde’s Folk City. It was 1961, and he had only just started booking gigs at the Italian restaurant and folk joint, which was already the epicentre of the Greenwich Village music scene. Dylan usually took the stage in work pants, a denim shirt and his Dutch Boy cap, his harmonica braced around his neck, and he addressed crowds in an exaggerated Okie accent, dropping consonants at the end of words.

“He was still mainly doing Woody Guthrie material at that point,” says Sylvia Tyson, one half of the harmonising act Ian & Sylvia. “That night, I guess he had decided that the way to get the audience on his side was to tell them a joke. And it was a really lame joke!

He said he’d invented this deodorant that didn’t stop the smell. Instead, it made you invisible. So nobody would know where the smell was coming from.” The groans from the Gerde’s crowd made it pretty clear that Dylan didn’t have a future as a stand-up comedian, but it does suggest that he was hungry to win over the tough Village crowd, to put himself on par with his heroes and friends. He might have been singing a lot of the same Guthrie covers as other aspiring folkies, but he was experimenting with new ideas and new angles, whether it was a joke to warm up his listeners or a new set of lyrics to confront social injustice.

Especially during 1961 and 1962, Greenwich Village was something like a laboratory for Dylan, who could test out ideas on a cramped stage in front of a small crowd, honing his act and his persona as he graduated to bigger venues. Sixty years later, that place and time loom large in his career – both as a moment of intense work and as a period of constant change. He was observing his peers carefully, sizing them up, borrowing what he could: a chord progression, a melody that might fit his lyrics, sometimes an entire song. It all served as raw material.

“Ian and I were mainly doing traditional material then, and everybody else was too,” says Tyson. “But when Dylan started writing, it was something that nobody really thought about. Then we realised that we probably all had that capability. If he can write songs, then we can write songs – because we were all on equal footing still. Or so we thought. We soon realised that there weren’t many people who could keep up with Bob.”