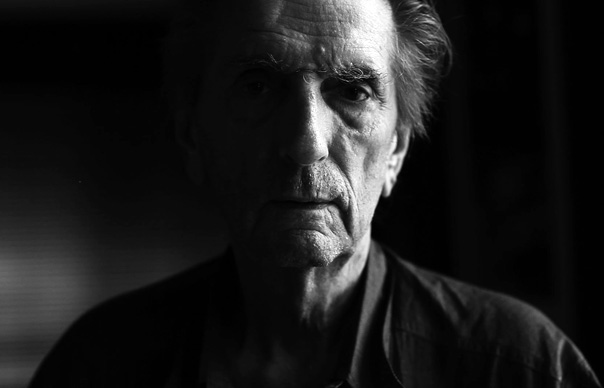

In 2014, I had the pleasure of interviewing Harry Dean Stanton for Uncut. He was 87, with over 250 film roles under his belt. Now in semi-retirement, he confessed he spent most of his time watching game shows. I’m addicted,” he confessed. “I hate the hosts and the people. I just like the questions and answers.”

“Which of your films do people ask you about the most?” I asked him. “Paris, Texas for one. Pretty In Pink was a huge hit for me. Molly Ringwald was awesome, a natural talent. Alien? Oh, yeah. I still get fanmail almost every week, pictures from all over the world on that movie. That’s one of the most popular films I’ve done. Am I still working? Just occasionally I’ll do something. I’m not working on anything right now. I did this film with Sean Penn [This Must Be The Place, 2011] that was one of my favourite roles. I played the guy who invented wheels for baggage. I met the guy and talked to him on the phone. It was an amazing experience. He told me how he invented it, the whole thing.”

Stanton’s career spanned over 50 years and included more than a 150 films, all of which benefited from his worn-out, hard bitten blend of philosophical cool and weary melancholy. Hearteningly, he continued to work well into his last decade: he made his final appearance earlier a few months ago in episode of Twin Peaks: The Return. Stanton was also the subject of a documentary, Harry Dean Stanton: Partly Fiction, which also spawned a soundtrack album. It found Stanton on splendid form, covering George Jones’ “Tennessee Whiskey”, Kristofferson’s “Help Me Making It Through The Night” and “Canción Mixteca”, which he originally recorded with Ry Cooder for Paris, Texas. “You know, I was a born singer, I sang when I was a kid,” he told me. “When people would leave the house I would get up on a stool and sing an old song by Woody Guthrie, or before him, “The Singing Brakeman”, Jimmie Rodgers. Anyway, I sang this country song, standing on a stool, thinking about this girl I was in love with. I was six years old, she was 18. Her name was Thelma. So I sang, “T for Texas, T for Tennessee, T for Thelma, That gal made a wreck out of me”.

Stanton grew up in Kentucky in the late 1920s/1930s and did some acting in high school (“I played Arthur Doolittle with a Cockney accent,” he confided). He served in World War II, as a gunner on an anti-aircraft gun. He played “Arthur Doolittle with a Cockney accent” in high school, moving into acting where he picked up regular TV work during the 1950s and early Sixties; a regular on TV westerns like Gunsmoke, The Rifleman, Laramie and Bonanza. There were early film roles in the late Sixties – most memorably Cool Hand Luke – though in the Seventies he aligned himself with the emergent New Hollywood scene, in Monte Hellman’s Two Lane Blacktop and Cockfighter, Peckinpah’s Pat Garrett And Billy The Kid, John Milius’ Dillinger and alongside Marlon Brando and Jack Nicholson in Missouri Breaks.

Stanton was very close to both Brando and Nicholson. “Jack is a very strong-minded person. Nothing was really bad, actually. We’re still very close friends. He gave me this advice in Ride In The Whirlwind [1966], he said, ‘Harry, I want you to do this part, but I don’t want you to do anything. Let the wardrobe do the character, just play yourself.’ That was the beginning of my whole approach to acting.” And on Brando: “During the last three years of his life, we spent hours on the phone and I went to his house a lot. What impressed me so much about him? He asked me once, he said, ‘What do you think of me?’ I said, ‘I think you’re nothing.’ He laughed. Eastern concepts. He knew what I was talking about. Marlon’s reminiscent of Dylan. Both very eccentric, complex characters.”

During the Eighties, Stanton worked with a new generation of filmmakers: Alex Cox (Repo Man), Ridley Scott (Alien), Wim Wenders (Paris, Texas), John Carpenter (Escape From New York), John Hughes (Pretty In Pink). They’re all superb performances – though it is as Travis in Wenders’ film that will probably be remembered as Stanton’s most memorable role.

“I was in Albuquerque, I think, with Sam Shepard,” he told me. “We were drinking and listening to a Mexican band. I said I’d like to get a part with some sensitivity and intelligence to it. I wasn’t asking for a part or anything, I was just free-associating, talking, right? I got back to LA, and Sam called me and said, ‘Do you want to do a lead in my next film, Paris, Texas?’ I said, ‘Only if everybody involved is totally enthusiastic about me doing it.’ Wim Wenders thought I was too old. He came to see me and finally he agreed to it after a couple of meetings. I just played myself. Travis was looking for enlightenment, I think. There was a girl on the film, Allison Anders. She’s a director now, but she was a student at UCLA then. She said, ‘That happened to me, I got that way when I was a teenager. I stopped talking.’ I said, ‘Why would you stop?’ She said, ‘I felt that if I talked I would lose it.’ I wish I’d used that a little more in the part. But just not talking itself is a powerful device.”

The Nineties opened with Wild At Heart – the start of a long relationship with Lynch which included roles in Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, The Straight Story and Inland Empire. Stanton continued to work, even though he drifted into semi-retirement. He popped up in Avengers Assemble – an analogue presence in a very digital world – This Must Be The Place for another old friend, Sean Penn, and lastly for Lynch in his revived Twin Peaks series.

I asked Harry Dean, finally, what advice he’d give his 18 year old self. “Study up on the Eastern religions,” he said. “They’re the only ones that are realistic. There’s no answer, see. Daoism and Buddhism are the exact same religion. And also the Jewish Kabbalah. They all say the same thing. The word ‘Dao’ means ‘The Way’, ‘the Nameless’. You can’t see it, smell it, touch it, or anything, but it’s there. There is no answer. That’s what Buddhism says. The Void, oblivion, no answer. To be in that state is an enlightened state.”

Follow me on Twitter @MichaelBonner