John Fogerty is out on an extensive tour of the US right now, so it seems a good time to dip into the archives and remind ourselves of this great feature from Uncut’s February 2012 issue (177). At the dawn of the ’70s, Creedence Clearwater Revival were the biggest band in the world – a brilliant and driven hit machine with deep roots in American tradition. By 1972, though, it was all over, and the ex-bandmates embarked on a bitter war that still continues, 40 years later. Here, Fogerty tells his side of a remarkable story – and then hears the very different stories of his old Creedence sparring partners. “I had so much anger,” says Fogerty, “I couldn’t play those songs…” Words: David Cavanagh

________________

Built in the Roaring Twenties, New York’s Beacon Theatre is known as the ‘older sister’ of the famous Radio City Music Hall. The 30-foot Greek goddesses towering either side of the Beacon stage have witnessed everything from opera to a series of Allman Brothers concerts. Tonight, John Fogerty is playing the first of two shows in which he’ll perform Creedence Clearwater Revival albums (Cosmo’s Factory and, tomorrow, Green River) in their entirety. Both million-sellers, they contain eight classic singles between them.

For various reasons, Fogerty refused to play Creedence’s music for almost 15 years after their 1972 break-up. He relented on a few occasions in 1986–7, following some gentle cajoling by Bob Dylan and George Harrison, but then came a typically Fogertyesque withdrawal – a gloomy, implacable silence – before his re-emergence in 1997 with Blue Moon Swamp. He officially began reintroducing Creedence songs into his sets that year.

Fogerty acknowledges the burden of engaging with the music (and, perhaps, demons) of his past. He compares it to the Eagles reuniting for their Hell Freezes Over tour. “Yes, there were long, dark times,” he tells Uncut. “I was miserable. I stopped playing guitar. I was a bitter person.” Claiming to be free of his grudges, Fogerty – whose dyed hair makes him appear younger than his 66 years – is animated onstage. His voice remains one of the most rip-roaring of rock’n’roll instruments, seeming to come with its own slapback echo. “This [Cosmo’s Factory] was an important record in the days when they still had vinyl,” he winks to the Beacon audience, “when people had Grateful Dead hairdos and smoked Jefferson Airplane cigarettes.”

The third song he plays is “Travelin’ Band”, a worldwide hit in 1970, which Fogerty wrote as an homage to Little Richard, a boyhood hero. But his tone turns sarcastic as he informs the crowd: “Of course, before you know it, lawyers got involved and I was sued.” The crowd don’t know what to say. Why has he mentioned a lawsuit? Why would someone sour the atmosphere of their own gig?

They might if they were John Fogerty.

________________

Creedence Clearwater Revival were an American phenomenon. From 1968 to 1972, they dominated FM and AM radio alike – an unusual feat – with a prolific run of glorious singles (“Suzie Q”, “Proud Mary”, “Bad Moon Rising”, “Green River”, “Fortunate Son”, “Up Around The Bend”). In 1969 alone, they earned three platinum discs and released three acclaimed albums (Bayou Country, Green River, Willy And The Poor Boys), as well as playing Woodstock and most major festivals. By late ’69, Creedence could have called themselves the biggest band in America. By mid-1970, they could have widened the parameters to ‘biggest band in the world’, since The Beatles, their only real competition in sales terms, no longer existed.

“Creedence took America by storm,” says Jake Rohrer, their former press officer and tour manager. “They had the broadest demographic imaginable. At Creedence concerts you’d see pre-teens, grandparents and literally every age group in between.” Some of their most enthusiastic fanmail came from US soldiers stationed in Vietnam, and inmates of federal prisons back home. “Creedence didn’t bring anything new to the culture,” Rohrer clarifies. “What they did was remind Americans from whence they’d come. Their lyrics were just so American.”

Creedence’s art was neither cosmic nor complex. Their grooves were smooth and warm, with steady, hypnotic momentum from Tom Fogerty’s rhythm guitar and a Memphis-like sense of economy. Paradoxically, their songs were haunted by anxiety and premonitions – malevolent moons and Biblical rainfall – like those from a Calvinist preacher crossed with a pessimistic meteorologist. Writing while bodies fell in a faraway war, John Fogerty composed allegories for a conflict which he emotionally opposed, but which, all the same, he could easily have joined. Some Creedence songs exchanged voodoo for parable, portraying a folkloric South of bayous, railroad stowaways (“flatcar riders”) and old-time courtesies. In Fogerty’s dual America, the bonfires of protest raged on the White House lawn (“Effigy”), but the people on the river were happy to share food with strangers (“Proud Mary”).

“Creedence made music for all the waylaid Tom Sawyers and Huck Finns,” pronounced Bruce Springsteen, inducting them into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame in 1993, “and for the world that would never be able to take them up on their most simple and eloquent invitation, which is: ‘If you get lost, come on home to Green River.’”

Fogerty’s post-Creedence depression in the ’80s had nothing to do with music. Mired in contractual disputes about royalties and publishing, he gradually lost his taste for the songs that the rest of the world loved. “I had so much anger,” he says of his long spell in the wilderness. “I was afraid that I’d start singing ‘Proud Mary’ and go off on a tirade. If one of my songs came on the car radio, I’d change the station. That’s why I couldn’t play those songs. I didn’t want that person standing in front of an audience.”

Does time heal all wounds? Intriguing comments by Fogerty last July suggested he would now be interested in a Creedence reunion. They last played together in 1983 (at a private party) and Fogerty explains that while he’s “not actively making overtures” to tour with them again, he’d be willing to listen to proposals. Uncut telephones Fogerty’s ex-colleagues to get their reactions. “Leopards don’t change their spots,” says an unimpressed Stu Cook (bass). “This is just an image-polishing exercise by John. My phone certainly hasn’t rung.”

“It might have been a nice idea 20 years ago, but it’s too late,” shrugs Doug Clifford (drums), who plays alongside Cook in Creedence Clearwater Revisited, a five-piece ‘reincarnation’ of CCR. Clifford adds: “I prefer the band I’m in now. We play Creedence better than Fogerty does.”

The three old friends and comrades, sad to say, have become used to aiming their remarks at the jugular.

________________

In one of his greatest songs, “Born On The Bayou”, John Fogerty sang nostalgically of the places where he’d grown up. He recalled the hound dog in the Louisiana backwoods; the Cajun Queen; the freight train “chooglin’” past on its way to New Orleans. There was just one thing. “Born On The Bayou” was complete fiction. It bore absolutely no resemblance to Fogerty’s childhood. Like all the members of Creedence, he hailed from the Northern Californian town of El Cerrito, nestled between Berkeley and Richmond, with pleasant views of San Francisco and the Golden Gate Bridge for the families who could afford a house on the hill.

John Fogerty was something of an anachronism. A serious, introverted boy, he grew up with a fondness for Uncle Remus stories and Disney’s Song Of The South, absorbing by osmosis a language of riverboats and catfish. Just like his contemporary Robbie Robertson (a Canadian), Fogerty would find his songwriter’s voice in the lexicon of the Southern states. “Let’s go all the way back,” he smiles. “Brer Rabbit. The Tar Baby. ‘Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah’. I found those things fascinating. Perhaps I identified with them more than kids who actually grew up in the South. I took note of them because they were so foreign to the place where I grew up.”

One of Fogerty’s favourite movies was Swamp Water (1941), directed by the émigré Frenchman Jean Renoir. Filmed on location in Georgia’s Okefenokee Swamp, it used real alligators and snakes and featured a spine-chilling shot of a human skull, balanced on a crucifix made of tree branches, grinning evilly above the foul water. Fogerty must have seen Swamp Water at an impressionable age. “Walter Brennan plays a guy living in the swamp,” he enthuses. “Dana Andrews is a government revenue guy trying to catch moonshiners – people making illegal booze – so he’s the enemy. But then Dana gets bitten by a snake, and Walter’s running around saying, ‘Cottonmouth bit! Cottonmouth bit!’ He nurses him back to health, but Dana goes delirious for a while and we see all these weird images. It’s a swampy, scary-looking movie and I was just fascinated by it.”

It was Bo Diddley’s “Who Do You Love?” that opened Fogerty’s eyes to “the darkness and spookiness” that could inhabit rock’n’roll. Along with a lifelong passion for echo-drenched Sun 45s, Diddley’s voodoo-steeped universe was a key influence on Fogerty’s thinking. “How can you not be inspired by a song about a guy wearing a cobra snake for a necktie?” he asks rhetorically. “And I liked anything to do with “gumbo” and “Little John the conqueroo” and “putting a spell” on somebody – those things seemed way cool.”

In 1959, Fogerty and two schoolfriends – Stu Cook, a well-to-do lawyer’s son, and Doug Clifford, a classmate of Cook’s with a drumkit – formed The Blue Velvets, an instrumental trio. All three boys were 14. John’s 18-year-old brother Tom, a singer, would sometimes borrow them as his backing group for gigs and demo recordings. In 1963, Tom joined The Blue Velvets permanently.

“The four of us spent the next few years,” Stu Cook recalls, “putting out unsuccessful records and touring around Central and Northern California, playing little towns and military bases. We had a variety of names: The Visions, Tommy Fogerty & The Blue Velvets, The Golliwogs. We put out half a dozen singles on the Scorpio label, a subsidiary of Fantasy. They got airplay in towns like San Jose, Lodi, Merced, all the little stations in Central Valley.” The idea of a musician playing out his days in one such backwater (“oh Lord, stuck in Lodi again”) would inform the Green River album’s poignant song “Lodi”. Doug Clifford remembers Lodi as “a small agricultural town with a seedy bar full of drunk farmhands and not a woman in the place”.

It had been Tom, not John, who led the charge in the band’s formative days, encouraging the younger lads to think of music as a viable career. Without his energy, they might have got nowhere. But it would be John who took over as singer, writer, leader and – ultimately – visionary as the years rolled by. A symbolic sibling shift took place, unspoken, for the benefit of all.

________________

The Golliwogs was a gimmicky British Invasion name foisted on them by Fantasy Records. The band hated it, mumbling into their collars when people asked them what they were called. Meanwhile, a more worrying matter presented itself. In late ’66, John Fogerty and Doug Clifford were drafted. Fogerty was placed in the reserve force. “I had a six-month active duty, plus a long period when I would do a whole weekend once a month, and every summer I’d do two weeks. And all that time I had the fear, at any moment, of being activated and sent to Vietnam.” Clifford had an even narrower escape. “I was two weeks away from being transferred to the Army and sent to Vietnam,” he confirms. “I even had the piece of paper in my hand, telling me where I’d be going.” Clifford calls it “the destiny of Creedence”. He says quietly, “Fifty-eight thousand Americans were killed out there, and hundreds of thousands were wounded, and John and I could have been among them.”

The Golliwogs re-signed with Fantasy – now run by new owner Saul Zaentz – in late ’67 and changed their name to Creedence Clearwater Revival. The three words came from different sources. Creedence was the Christian name of a friend of someone that Tom Fogerty knew. Clearwater was taken from a beer commercial. Revival (which they liked to say was the most salient part of the name) signified a rebooting of their youthful ambitions and a return to ’50s rock’n’roll values. “I didn’t like the idea of those acid-rock, 45-minute guitar solos,” says John Fogerty today. “I thought music should get to the point a little more quickly than that. I was a mainstream rock’n’roll kid, and I also had a country blues ethic. Lead Belly was a big influence. I learned about him through Pete Seeger. When you listen to those guys, you’re getting down to the root of the tree.”

Despite the constant threat of John or Doug being suddenly dispatched to Vietnam, there was a growing feeling in the Bay Area that Creedence had a promising future. Promoter Bill Graham expressed interest in managing them. “They’d play Winterland and the Fillmore West, third on the bill, and blow everyone off the stage,” declares Jake Rohrer. Fantasy were confident, too. “We sat in Saul Zaentz’s kitchen,” recalls Cook, “and he told us, ‘When you guys are successful, we’ll tear up this contract and give you a real deal.’” Cook sighs. “Well, we kept our side of the bargain. He didn’t.”

Their 1968 debut album, Creedence Clearwater Revival, was a modest seller at first. Its standout track was “Suzie Q”, an eight-minute version of a 1957 hit by Louisiana rocker Dale Hawkins. For all his scepticism about long solos, Fogerty stretched out penetratingly on guitar while Creedence’s rhythm trio laid down a sublime slow boogie. An edited version, issued by Fantasy as a single, was picked up by AM radio and reached No 11 in the charts. Nine years into their career, Creedence were finally a smash. That summer, on the day that he received his discharge papers from the Army, Fogerty wrote a song about a man shaking off the pressures of the city and finding harmony on the river. Fogerty called it “Proud Mary”.

________________

The first of Creedence’s true monster hits, “Proud Mary” would have topped the American charts if 1969 hadn’t been the annus mirabilis of bubblegum pop. As it was, Tommy Roe’s infernally catchy “Dizzy” kept Creedence at No 2, but “Proud Mary”, later covered by Ike & Tina Turner, Elvis Presley and a couple of hundred thousand bar bands, was already on its way to being established as a landmark in rock’n’roll. “Bad Moon Rising”, another million-seller, followed it to US No 2. As soon as the bad moon began to wane, it was promptly replaced in the charts by “Green River”, which sat (once again) at No 2 behind The Archies’ “Sugar Sugar” – another bubblegum behemoth – in September.

“We worked on a 12-week cycle,” explains Clifford. “John’s theory was that if we ever went out of the charts, our career would be over and we’d be forgotten. None of our peers thought that way. It put a lot of pressure on John. A lot of pressure on all of us.” Talking to Fogerty now, he gives every indication that the pressure stimulated him immensely. In 1969–70 he was arguably America’s most socio-politically significant songwriter since Dylan. Ask Fogerty about any song’s origins and he quickly applies his answer to the context of the times. “Effigy” (on Willy And The Poor Boys) was his response to President Nixon emerging from the White House one afternoon and sneering at the anti-war demonstrators outside. (“He said, ‘Nothing you do here today will have any effect on me. I’m going back inside to watch the football game.’”) “Fortunate Son”, angry and indignant, was an attack on the iniquities of the draft system, which saw rich men calling in favours to help their sons avoid the Vietnam bombs and bullets. “Run Through The Jungle” warns of a different kind of arms proliferation – this time at home – though its gun control message, couched in metaphor like most Fogerty songs, didn’t stop it being adopted as an anthem by US troops in the Vietnam jungles. Fogerty wrote the bulk of Creedence’s Bayou Country album, meanwhile, while a muted TV in the corner of his room showed horrified reactions to the assassination of Bobby Kennedy in June 1968.

“I would sit in my little apartment – which was very sparse – and stare at the wall. That’s how I wrote. I would stare at it all night. There was nothing hanging on the wall, because I didn’t have any money for paintings. It was just a beige wall. It was a blank slate, a blank canvas. But it was also exciting. I could go anywhere and do anything, because I was a writer. I was conjuring that place deep in my soul that was me.”

A loner who rarely socialised, Fogerty put Creedence through their paces as musicians. They rehearsed doggedly until songs’ arrangements were inch-perfect, enabling them to record whole albums in a matter of days. The emphasis was on being well-drilled, well-prepared, almost like the army that Fogerty had recently left. Creedence had a ‘no alcohol’ rule in their dressing-room. They disdained the drug culture. “The San Francisco bands called us boy scouts because we didn’t get high and we were all married with families,” laughs Clifford. Fogerty’s natural discipline (and self-confessed fear of LSD) made him a Roy Keane in an era of Balotellis. “At a time when rock’n’rollers were developing increasingly flamboyant looks,” relates Russ Gary, a recording engineer on several Creedence albums, “Fogerty, in his simple jeans and flannel shirt, came across as more of a shaggy haired workingman than a rock star. But even just standing around, he gave off an intensity that drew your eye to him.”

As they travelled around the country, Creedence were thrilled to be embraced in Louisiana and Georgia, where they’d been somewhat nervous about playing. Cook: “We were celebrating their culture and they liked us. The real disconnect was that they thought we were from the South. When they found out we were from California, they scratched their heads.” Jake Rohrer: “I remember Duck Dunn of Booker T & The MG’s telling me that when he found out the guys who’d done ‘Born On The Bayou’ were from Berkeley, he was going to go and burn all his Creedence records.” In the event, Creedence and The MG’s became friends and later toured together.

In the studio, Creedence shunned the psychedelic effects that other bands relied on, and instead used slapback echo to get the sounds of the mid-’50s Sun singles that John Fogerty adored. “I was greatly influenced by the early records of Elvis Presley and I just thought that was the way that music should sound,” he says. “I also loved Carl Perkins’ great records from that era. And also Roy Orbison’s ‘Ooby Dooby’ [which Creedence covered in 1970] and ‘Go Go Go’.” Fogerty would never outgrow the traditions and protocols of the ’50s. His aim was to make music that sounded great coming out of a radio, not music that hippies could trip out to on headphones. “This statement holds true for everybodyin Creedence: simple is better, less is more,” Fogerty says. “But even though it’s simple rock’n’roll, everybody will have a certain role within the framework. Tom’s guitar playing may just sound like a guy in a garage strumming away, but it’s awfully specific.” Cook adds: “People called it swamp-rock. We never called it that. We just called it rock’n’roll.”

Green River is Fogerty’s favourite Creedence album. The second of the three albums they released during 1969 (an amazing statistic which was matched by Fairport Convention in Britain), Green River was, says Fogerty, “something that I’d been carrying all of my life. Musically, Green River was everything that I was about. I really enjoyed making it. I was really focused with the arrangements, the rehearsals, the necessities for each song.

“The inspiration for ‘Bad Moon Rising’ was an old movie called The Devil And Daniel Webster. It’s an old tale about the Devil seducing some poor guy who’s wishing for a better life. In steps the Devil: ‘I can promise you untold success and wealth.’ ‘You can?’ ‘Yes. All you have to do is give me your soul.’ The movie made a big impression on me – especially a scene where there’s a hurricane during the night and the guy is cowering in his barn. The next morning he opens the door and it’s a beautiful sunny day. He looks over and sees his neighbour’s field trounced to the ground by the hailstorm, but his own crops are standing straight up. That was a very powerful image to me. That was my inspiration for ‘Bad Moon Rising’. I saw the movie again recently and the scene was so subtle, and so hard to hear, that it’s a wonder I got any inspiration from it. I guess in the old days movies were more subtle.”

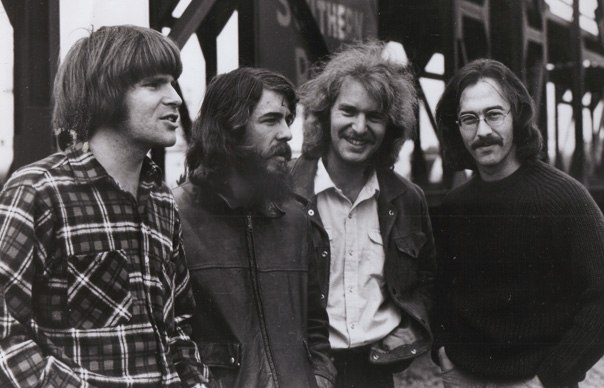

Creedence made a rare foray outside America in 1970, flying to Europe and headlining the Royal Albert Hall. Jake Rohrer remembers arriving in West Germany “and finding we were bigger than The Beatles”. Cosmo’s Factory, released in July, was their fifth album in two years. Its title was a reference to the band’s Berkeley office space (The Factory) and also to their gregarious drummer Clifford (whose longtime nickname was ‘Cosmo’). The album’s front cover showed the four of them caught by a camera in an off-duty moment, a proudly uncool quartet who looked more like lumberjacks than rock stars. The album was enormous and the hit singles kept coming. Cosmo’s Factory had six of them. While San Francisco longhairs across the bridge scoffed at their commercialism, Creedence henceforth made a point of releasing double A-sides. And invariably both songs would have an uncanny knack of cutting through the weasel words and speaking directly to all sections of the population.

Clifford: “‘Fortunate Son’ and ‘Who’ll Stop The Rain’ – which was about Nixon – were very powerful messages. Some of the other bands on the political left were writing stuff like ‘fuck the pigs’, but who’s going to listen to something like that except the hardcore freaks? To be able to spread a message to a divided country, so that both sides heard it – and to do it poetically and descriptively – that’s where the power of John’s songs lay. We reached the masses with strong messages and feelgood music, and that really was our greatest achievement.”

In the autumn of 1970, Creedence were on top of the world. Nobody could have foreseen what would happen next. Having captured America’s hearts and minds, the four men somehow found a way to implode – with toxic effects on long-held friendships and a relationship between two brothers. It was to be the most acrimonious and protracted divorce that rock’n’roll has ever known.

________________

It began, John Fogerty recalls, with a band meeting. That in itself was odd. Creedence didn’t have band meetings. Creedence was a benevolent dictatorship in which the will of the rhythm section yielded to the decree of the flannel-shirted leader. Ever since “Proud Mary”, the system had worked with spectacular results. Fogerty was therefore irritated and nonplussed, towards the end of 1970, to be confronted with the first mentions of an unwelcome concept called democracy. “Suddenly everybody wanted to be a general,” he says ironically.

Part of the problem was that Creedence, even at their height of their fame, were a remarkably small operation. They travelled with two or three roadies, plus Rohrer, and that was it. They had no manager, no booking agent, no PR firm, no entourage. They were the equivalent of a small family firm that accidentally creates a brand name as marketable as Coca-Cola. “John was our manager,” Clifford groans. “Bad idea. He had no concept of the business side. Zero. None. Nada.” Stu Cook, who has a business degree from San Jose State University, gives a withering assessment of Fogerty’s managerial shortcomings. “He condemned us to a career that effectively never became professional. Doug and I call it El Cerrito Syndrome. We were always limited by John’s vision of how a band is supposed to be run. We were tied – and we’re still tied to this day – to the worst contract signed by any band in history. We said to John, ‘Look, you didn’t get us a new contract with Fantasy like you were supposed to do, like you said you’d do. You’re not qualified to be the manager. We’re the number one band in the world and we deserve a real manager.’ So what does John do, in an act of what I can only describe as brutal cynicism? He brings us Allen Klein.”

Klein was sent packing after one meeting and Fogerty resumed management of Creedence. A contract renegotiation was put on the table, but it would drag on for a year, complicated by Saul Zaentz’s offer of a percentage in Fantasy as a sweetener. Cook describes the percentage as “huge”. Clifford calculates it as “monumental”. Fogerty disputes their accounts, arguing that the percentage was minuscule and that only a pair of idiots would think otherwise. Cook counters that Fogerty was a novice at reading contracts and should have asked a lawyer to help him understand it. Fogerty refused to sign the contract. Cook and Clifford claim that his intransigence cost them tens of millions of dollars.

________________

If the restrictive clauses and meagre royalties of Creedence’s 1967 contract have denied Cook and Clifford the earnings they feel entitled to – well, that could be termed a ‘professional’ grievance. But so much of Creedence’s disintegration is personal. Fogerty’s stranglehold over their affairs was challenged, crucially, by his brother Tom, who had grown resentful of John’s refusal to allow him a more prominent role. “Tom had put up with a lot of shit from John,” remarks Clifford, Tom’s closest ally in the group. “I think Tom was expecting John to say, ‘OK, now we’ve achieved our goals, why don’t you start singing a few of the songs?’ Tom had a great voice, kinda like Ritchie Valens. Tom would have done a damn good job on ‘La Bamba’. But John didn’t want him to sing it, in case we had a hit with it. He didn’t want Tom to succeed.” John insists he simply didn’t want to mess with a successful formula.

Creedence’s sixth album, Pendulum, had a fuller-sounding production than its predecessors, and had been a long time in the works while John overdubbed keyboards and saxophones. Engineer Russ Gary remembers that Cook, Clifford and Tom Fogerty were only in the studio for “two or three days at the most”. Pendulum was launched to the media with an expensive PR event to which 200 journalists were invited – a very un-Creedence-like evening which John maintains he attended under protest. The party had been Tom’s idea.

Tom, nevertheless, left Creedence in early 1971 to begin a solo career. The others considered asking Duck Dunn to join, before deciding to continue as a trio. The bombshell lay just around the corner. Forty years later, the accusations are so vehement on both sides that it’s impossible to know who to believe. Fogerty complains that Cook and Clifford concocted a false story about him giving them a bizarre ultimatum in a limousine after a concert in San Diego. Cook and Clifford are adamant that the ultimatum (and the limo) were real. Fogerty says that Cook and Clifford demanded to write and sing a third of the next album each, or they’d leave. Cook and Clifford reject this completely, alleging that Fogerty threatened to leave if they didn’t write and sing a third of the next album each. It seems a shocking allegation for them to make, because it implies that Fogerty would intentionally sabotage an album – not to mention tarnish Creedence’s legacy – in order to make his two bandmates look inadequate.

“John wanted out,” says Clifford with contempt, “but first he wanted to punish us for supporting Tom. He was cutting his nose off to spite his face. That’s the way John Fogerty does things. Stu and I wanted some input, but the last thing we wanted to do was sing. But, anyway, we wrote and sang three songs, and of course the album was doomed to fail. John told the press that we’d put a gun to his head, but it was quite the opposite. It was a cruel lie.” Mardi Gras (1971), one of the most scathingly reviewed albums ever, was the last record Creedence would ever make.

“I had a pretty good idea that the album would be dreadful,” says Fogerty, who blames Cook and Clifford for forcing their songs on him. “I’d known these guys since high school and I figured I had a good handle on their abilities. The phrase I kept repeating to myself was, ‘I guess they deserve a shot.’ But I was dreading the results. Jon Landau in Rolling Stone called it the worst album he’d ever heard. And I agreed. The other guys didn’t. They thought the album was really cool.” He laughs. “They changed their tune later.”

Creedence split in 1972. Fogerty released The Blue Ridge Rangers in 1973, a country-bluegrass album on which he played all the instruments himself. In the years following Creedence’s demise, the real poison seeped in. Cook and Clifford became convinced that Fogerty’s mismanagement of the band’s affairs had got them into trouble with the IRS. In the meantime, the bandmembers had lost millions in an offshore banking scheme that turned out to be a swindle. “The full picture slowly unfolded,” says Cook, “that not only were we broke but we were also in trouble with the authorities. We found out more and more of what had actually gone on in John’s negotiations with Fantasy. More hard feelings developed. We got more and more isolated and estranged from John over the years.”

________________

Fogerty’s solo career faltered in the mid-’70s. He stopped recording, angered by a clause in his Fantasy contract that seemed to demand greater and greater amounts of product as each year passed. Jake Rohrer, who worked for Fogerty until 1977, questions his interpretation of the wording. “I disagree with John’s comment that the contract was a prison sentence. I personally thought that John wasted two decades of his life waging a war with Saul Zaentz.” Either way, it became dangerous to mention Zaentz’s name in Fogerty’s presence during the ’80s. His 1985 comeback album for Warner Bros, Centerfield, railed at Zaentz on not one but two tracks (“Mr. Greed”, “Zanz Kant Danz”), to the disbelief of his former colleagues. “He even told Warners, ‘I’ll indemnify you against lawsuits’,” says Doug Clifford. “He was still carrying all this crap from 15 years ago. He’s free, he’s won, he’s on the biggest label in the world, but he can’t get his foot out of the bucket of shit. So, of course, he gets sued.”

In spite of their animosities, Creedence played together twice during that decade. Both were private occasions. First came Tom Fogerty’s wedding in 1980. Then John Fogerty showed up at a 1983 high-school reunion in El Cerrito and Creedence performed as The Blue Velvets, shaking a tail feather the way they’d done in 1959. But the problems between the Fogerty brothers remained unresolved. At some point in the ’80s, Tom, who had undergone several operations on his back since 1974, caught AIDS from an unscreened blood transfusion. By 1989, his illness was a matter of desperate concern. Tom had one last request. He wanted Creedence to play as a four-piece one more time, if only in his living room, before his inevitable return to hospital. John declined the request. “Finally,” recalls Stu Cook, “when Tom couldn’t even lift his arm properly because he was so weak, John said, ‘OK, I’ll play with you.’ Just a little bit late there, John.” Admitting that he did not make his peace with Tom (who died in 1990), John reveals why he felt unable to grant him his wish. Some of the last words Tom ever uttered to John while he lay in an Arizona hospital were: “Saul Zaentz is my best friend.” They were the six words that John Fogerty could never forgive.

Creedence were inducted into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame in 1993. For Jake Rohrer, it was “the saddest chapter of their career”. It was Fogerty at his most ruthless: he’d learned Cook and Clifford had sold their Creedence veto rights to Zaentz for five-figure sums, and he was not happy about it. Cook and Clifford arrived at the Hollywood centre with their families, expecting to play Creedence hits with Fogerty that night. They were informed by the stage manager that Fogerty would be performing with an all-star band (including Bruce Springsteen and Robbie Robertson) instead. “It was humiliating,” says Cook. “It was like John thought he was getting inducted, instead of Creedence. He thought he could exclude us.” Booing was heard when Fogerty took the stage. “It was a terrible night,” concludes Rohrer, “and all it did was pour kerosene on the flames.”

In Hank Bordowitz’s well-researched Creedence biography, Bad Moon Rising (1998), there are 31 index entries for ‘Fogerty, John, bitterness and rage’. Fogerty claims to lack venom these days (“I’m no longer a prisoner of my own device, to quote a Don Henley line,” he assures us), but it’s noticeable that, during a follow-up interview, he repeatedly describes a former business associate as a cheat, a liar and the second worst man in history after Saddam Hussein.

Clifford, who regards Fogerty’s career arc as “kind of Shakespearean” attempts to put a positive slant on Creedence’s ongoing hostilities. “The good news is, the music is what’s important,” Clifford says. “Look, we all made mistakes. It’s unfortunate, but the legacy of the music is still there, intact.” The bayou will surely freeze over, however, before Creedence Clearwater Revival share a stage again.