The career of Lloyd Cole & The Commotions began with a fortuitous false start. Their first single, “Down At The Mission”, was pulled at the eleventh hour when the band signed to Polydor, and one can only assume they’ve been counting their blessings ever since. Heard here (officially) for the first time, this frantic slice of blue-eyed funk reveals a subsequently unexplored fascination with cheesy synths, shrieking falsetto and slap bass. Imagine early Spandau Ballet fronted by a drunk Edwyn Collins and you’re still only halfway there.

It’s not pretty, but then that’s partly the point. Collected Recordings is a warts and all excavation of one of the most idiosyncratic and sporadically brilliant bands of the ’80s. Running to 66 tracks and five CDs, it includes remastered versions of the group’s three albums – Rattlesnakes (which has never sounded better), Easy Pieces and Mainstream – plus two further discs of B-Sides, Remixes And Outtakes and Demos And Rarities. All but two tracks on the latter are previously unreleased, while six songs have never been heard before in any form. There’s also a DVD of videos and TV performances, and a 48-page hardback book.

This is, then, very much the final word on a band which formed in 1982 in Glasgow, where Buxton boy Cole was studying English Literature and Philosophy. A 21-year-old who had read a few books and was keen for everyone to know it, Cole’s aesthetic was hewn from the milieu of New Journalism, Leonard Cohen songs and the French New Wave. Much of the action here takes places in basement rooms littered with paperbacks, art magazines, red wine, unfathomable women, strong cigarettes and unfinished first novels.

Majoring in undergraduate chic, Cole strolls through the extended narrative in his black polo neck and floppy fringe, alongside Julie and Jim (a knowing nod to Truffaut), Arthur Lee, Joan Didion, Sean Penn, Truman Capote, Grace Kelly, Norman Mailer, Jesus, Eva Marie Saint and Simone De Beauvoir. The romantic yearning – which is acute – is buried beneath a protective layer of verbosity; for Cole, love is a girl who can spell “audaciously”. To what extent this represented autobiography rather than a richly imagined internal life doesn’t much matter. As a lyricist Cole presented a fully-formed world view from the off, delivered in a vibrato-heavy voice somewhere between a nervy gulp and an affirming swallow.

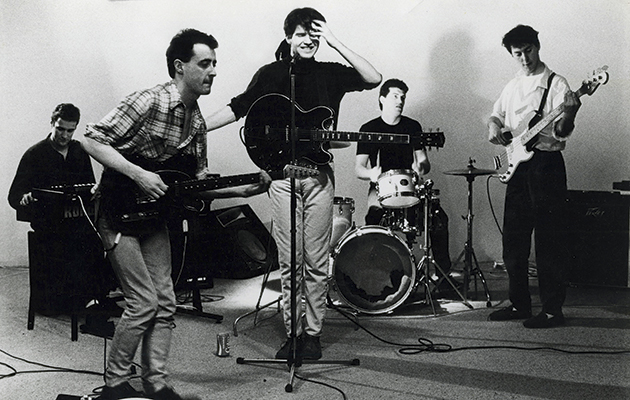

The four Commotions – Neil Clark (guitar), Blair Cowan (keyboards), Lawrence Donegan (bass) and Stephen Irvine (drums) – animated this vision most successfully on Rattlesnakes. There’s nothing indie about the band’s 1984 debut. This is pop classicism, a thrilling blend of sparkling guitars, sighing female singers and elegant strings. Drawing on The Byrds, The Velvet Underground, Bob Dylan, Postcard Records and a smattering of blues, folk and soul, Rattlesnakes pivots on its trifecta of instant classics. Demos of “Perfect Skin”, “Forest Fire” and “Are You Ready To Be Heartbroken?” reveal them to be fully-formed masterpieces at an early stage, but Rattlesnakes’ greatness endures because it holds the line from top to bottom.

The title track is a glorious blend of quicksilver acoustic guitar, Anne Dudley’s vaulting string figure and Cole’s literate smarts. The lovely, lovelorn “Patience” is as good as anything they ever recorded, and while Springsteen was singing about ’69 Chevys, Cole prefers the “2CV”, hymned over a gentle acoustic backing which vaguely recalls Big Star’s “Thirteen”. “Four Flights Up” reanimates the helter-skelter blues of ’65 Dylan, while the wonderful “Forest Fire”, a masterclass in understated dynamics, ends with the postmodernist conceit of Cole commenting upon his own working process – “it’s just a simple metaphor, for a burning love” – which manages to be funny, clever-clever, and oddly touching. Contemporary B-sides like “The Sea And The Sand” and “Andy’s Babies” convey an admirable strength in depth, while the previously unheard “Eat My Words” finds Cole crooning like a callow Scott Walker.

As Cole tells Uncut, “1984 was our year”. Rattlesnakes was widely lauded, spawned three modest hit singles and stayed in the Top 100 for 12 months. It proved a hard act to follow. Easy Pieces, released in November 1985, met with a more muted critical response, but although its flaws are obvious, it holds up rather better than its low-key rep suggests. Producer Paul Hardiman, so innovative and accommodating on Rattlesnakes, was replaced by Clive Langer and Alan Winstanley, who steered the band towards a more obviously commercial sound, instantly heralded by the punchy horns on opener “Rich”. The strings remain, alongside prominent accordion, smoothly soulful backing vocals, and burbling synth drums on the rather limp lead single, “Brand New Friend”.

Recorded by a band already second guessing its natural instincts in the pursuit of commercial traction, there is plentiful evidence of Second Album Syndrome. “Minor Character” and “Grace” are not just poor songs, they find Cole already flirting with self-parody, but such moments are in the minority. The headlong rush of “Lost Weekend” recounts a disastrous sojourn to Amsterdam over chiming Rickenbacker. Second single “Cut Me Down” is simple and affecting, while the sombre “James”, an empathetic dig in the ribs to an “impossible” acquaintance hiding from a “thoughtless, heartless world”, is a quiet highlight, drifting on a sound-bed of martial drums, mournful organ and chiming guitar.

The ‘Rarities’ brief of Collected Recordings is at is most instructive sketching in the detail of the two-year gap between Easy Pieces and 1987’s Mainstream. There’s a fine alternate version of “Jennifer She Said”, recorded with Stewart Copeland and Julian Mendelsohn, and pickings from sessions with Chris Thomas, including the excellent and unreleased “Everyone’s Complaining”, meatier than anything on Mainstream. This generous rump of unheard material includes the pleasingly odd “Old Wants Never Gets”, on which, says Cole, “Blair and I are trying very hard to be Prince”.

The number of producers tried out for Mainstream – the band eventually settled on Ian Stanley – speaks of its somewhat compromised nature. The title is a knowing wink. A calculated tilt at a bigger, smoother rock sound, Mainstream is sleek and mid-paced, but although the frantic energy of old may have dissipated, it has its moments. “Jennifer She Said” is punchy pop, “My Bag” flashes by in a blizzard of cocaine-themed puns and pithy put-downs of the executive life, while “29” is an ambitious departure, an atmospheric ballad which nods to Cole’s long-standing love of David Bowie. Too often, however, the songs play second fiddle to the sound. “Sean Penn Blues” – perhaps the most ’80s song title ever – has little discernible shape or purpose; “Hey Rusty” aims for the E Street Band but settles for Deacon Blue; the title track meanders before setting its sights on an epic, U2-shaped climax.

Mainstream didn’t shift the requisite seven-figure numbers and Cole split up the group in 1989. Their concluding experiment in maturity failed partly because Lloyd Cole & The Commotions excelled at making young man’s music: occasionally clumsy and anxious to show off, as young men tend to be, but also brimming with words, ideas and the propulsive energy of precocious youth. Collected Recordings bears deep and eloquent testament to Cole’s view that “we did one thing really well for a little while”. It’s not a bad epitaph.

Q&A

LLOYD COLE

How hands-on were you in putting together the boxset?

There are 769 emails in my mailbox to do with making this record. It took at least as much work as making a normal album, it was a massive undertaking. We found everything, all the rare tracks, things I didn’t have or had forgotten. There’s stuff from between Easy Pieces and Mainstream where you can hear us trying to see what we could do next. It makes quite a fun story.

Did it make you reassess anything about the band?

Our strength when we began was that I had an aesthetic that everybody else was willing to buy into. The longer we existed the more we became democratic, and to be honest I can’t really complain about that, because I had less ideas. We were up against Thatcher, democracy seemed like a good idea! It was a lovely band to be in, but each year that went by it was more difficult. It was natural that it only had a limited lifespan, but I think the body of work we managed to put together is pretty great.

Your initial trajectory was rapid. What were the high points?

Writing “Are You Ready To Be Heartbroken?” in September ’83 was the moment where I thought, ‘Oh I can do this.’ The following month I took home the portastudio we shared and wrote the essences of “Forest Fire” and “Perfect Skin” in one weekend. Then I knew we were onto something. Being in NME, being on Top Of The Pops, those were the yardsticks. That’s where David Bowie had been, that’s where Morrissey already was, that’s where we wanted to be.

Did you suffer from the curse of the classic debut album?

I don’t think that was the problem. The problem was we grew up with Bowie, thinking that we had to reinvent ourselves with every record, and that’s a curse. So rather than doing Rattlesnakes Mk II, we decided to make more of a pop electric record. I think the good tracks on Easy Pieces are great and the bad tracks are awful.

Were you under external pressure to follow Rattlesnakes with a hit?

There was no expectation with Rattlesnakes, from a business point of view. Five months later we did a gig in Bristol and every record company from the Polygram group worldwide was there. I guess their eyes lit up with dollar signs. It wasn’t just the record company. There was this strange period in my life when it looked like I was going to become some kind of superstar – I never did – but what happened as a consequence was that we allowed ourselves to be persuaded that if we didn’t meet the Christmas ’85 release date there would be a chance that we’d be forgotten. I think that was the beginning of the end. People waited five years for [the Blue Nile’s] Hats, and people would have waited five years for the next Commotions record, but we were insecure in our position.

Mainstream sounds like a compromised album.

We basically thought we could make something better than a Simple Minds record. It’s possibly the most sonically beautiful record I’ve put my name to, but there’s not many actual songs. I think “My Bag” and “29” are great songs, but there’s also some excuses for songs, and a lot of long play-outs. Ian Stanley had come from producing Songs From The Big Chair by Tears For Fears, and we allowed ourselves to get into this position of thinking that selling less than a couple of million albums was failure.

What do you remember about breaking up?

It was very sad, and I was splitting up with my girlfriend at the same time. We weren’t childhood friends who grew up with a gang mentality, we became friends through playing music together, but you can’t not be close to a bunch of blokes you play with for years. It was upsetting and difficult. If there had been a great idea for a fourth Commotions record we would have made it, but there wasn’t. As a consequence, all the aspects of the lifestyle that made me unhappy weighed on me more. I felt that my being there was necessary for everybody else to make a living, and I didn’t like that.

You reformed to tour in 2004. Is there a temptation to do so again for the box-set?

They wanted me to do some solo shows, but I’m sure I’ll be able to, I’ve got other stuff going on. It’s too late for the five-piece. When we got together in 2004 it was a lot of fun, but I was at my limit. It required a different type of energy to that which I have these days. I don’t think it would be possible now, but I don’t think any of us have any regrets.

INTERVIEW: GRAEME THOMSON

The History Of Rock – a brand new monthly magazine from the makers of Uncut – a brand new monthly magazine from the makers of Uncut – is now on sale in the UK. Click here for more details.

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.