If Danny Fields didn’t exist, it’s doubtful anyone would invent him – unless it was some hipster Woody Allen making a wild new musical version of Zelig, about an unlikely figure who somehow happened to just be there for 90 per cent of the most interesting moments in American rock and roll between 1965–1977.

Unlike a Zelig, though, Fields wasn’t just simply there, blending in. Variously journalist, scout, PR man, manager, fixer and “underground mayor,” to quote Alice Cooper, he helped shape the scene. He’s hardly a household name, but his ears are responsible for a lot of the music played in all the coolest households over the past fifty years.

If you’re glad The Doors broke through, be thankful Fields, as their self-appointed publicist, was around to suggest “the song about fire” should be a single. If you ever shook to The Stooges or MC5, you owe him a drink – he got Elektra to sign both bands with a single phonecall to label boss Jac Holzman who, by that point, had made Fields “company freak,” hired, essentially, to stay up later than everyone else.

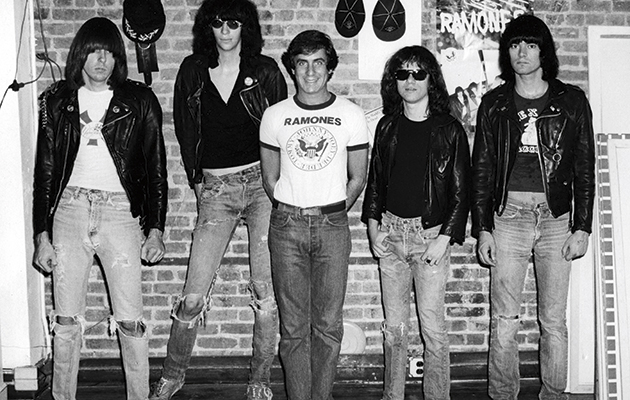

Ramones fans should know him as the man who discovered the band in 1975 and became their first manager. They parted in the early 1980s, but not before Da Bruddas wrote one of their most glorious songs in his honour, “Danny Says”. Scholars of American pop’s ripped underbelly might recognise Fields’s name from the footnotes through his associations with these bands, not to mention The Velvet Underground. But seeing it all laid out up front in director Brendan Toller’s documentary – that this one guy had his antenna up in a way that put him right in the middle of it time and again – is remarkable.

More startling yet are the other flashpoints the film uncovers. You know those giddy photographs of Bob Dylan meeting Patti Smith for the first time backstage in Greenwich Village in 1975? Fields was behind the camera. Before that, he was the one who first invited Smith and Robert Mapplethorpe, two wide-eyed kids persistently hanging around, to join the backroom gang at Max’s Kansas City. Before that, in the same fabled New York hangout, he introduced David Bowie to Iggy Pop.

If that’s not enough, how about this: in 1966, as an editor on teen fan mag Datebook, he was the one who sensed a quote John Lennon had given months earlier without fuss to The Evening Standard was maybe worth highlighting. Thus the world got the “more popular than Jesus” furore that saw The Beatles’ US tour met with death threats, and fuelled their decision to stop playing live.

This all makes such a fantastic surface you can forgive Toller’s film for not going far beneath. We get a taste of Fields’s persona – dry, catty, sharp, simultaneously unimpressed yet in love with it all – but no idea of what might tick inside. In this respect, the opening is most poignant. Illustrated with glowing home movies, we glimpse a straight early life as a Jewish boy in suburban Brooklyn, where Fields was born Daniel Feinberg in 1939. Already, though, there are kinks: his doctor father left a bowl of amphetamines on the sideboard, like sweets, and Danny and his mother would help themselves.

Openly gay, Fields studied law, but was more interested in “hanging out with a bunch of dissolute faggots.” Dropping out, he met his destiny when he fell in with Andy Warhol’s Factory crowd, forming close friendships with Edie Sedgwick, Nico (he was later responsible for bringing her and John Cale to Elektra for the magisterial Marble Index) and Lou Reed.

Shortly before his death, Warhol told Fields he’d like to film his story. Fulfilling the prophecy, Toller’s documentary is likely very different to anything Andy might have made, but he’s indebted to Warhol for lessons he taught Fields, who developed the habit of documenting his life, down to regularly tape-recording conversations.

Toller interviewed Fields over several years, and brings in Iggy, Alice, Jac Holzman and many others. But the gems come from Fields’s own archive, best of all his C-120 tape of Reed’s uncharacteristically enthusiastic reaction the night Fields first played him The Ramones: “That is, without doubt, THE most fantastic thing you’ve ever played me!”

It’s telling that the documentary ends on the Ramones adventure: there’s nothing about what Fields has done since. You sense he could say things about the past three decades, too. But, then, maybe those stories just aren’t as good.

EXTRAS: Great 1969 promo for Nico’s “Evening Of Light” featuring Iggy; Fields Q&A; more 1975 audio of Fields and Lou; interviews; trailer. 7/10