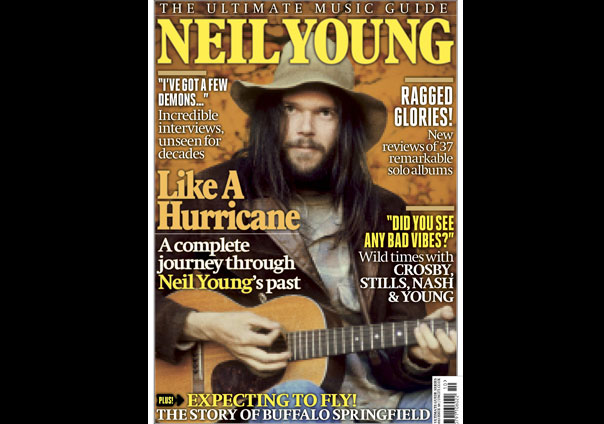

The Neil Young Ultimate Music Guide that I wrote about here (along with a review of the forthcoming “Live At The Cellar Door” set) is on sale now, so I thought it might be useful to post a sampler of what you might expect in this Uncut special: namely, this piece by me on 1996’s underrated “Broken Arrow”. Every Neil album is reviewed in comparable detail – you can find details of where to buy the mag here…

On November 8, 1996, a conceivably weary Crazy Horse fetched up at the Meadows Music Theater in Hartford, Connecticut. A couple of songs from the show made it onto a live CD, Year Of The Horse, the following year: “When You Dance”, in fact, opens that set. The first thing you hear on the album is a heckler complaining, “They all sound the same!” In what would eventually become a wry mantra for him, Neil Young has the perfect response ready. “It’s all,” he claims, “one song.”

A year earlier, David Briggs had died, and Young spent much of 1996 attempting to honour his old producer in as uncompromising a way as possible. The first half of the decade had seen Young accept a sanctified status among a younger cohort of Nirvana and Pearl Jam fans. Now, though, the idea of capitalising upon the success of Mirror Ball appeared unutterably vulgar. His next move was not to hop genre with the kind of cantankerous zeal he displayed in the 1980s. Instead, Young subverted his success by being antagonistically predictable: by reassembling Crazy Horse, giving them license to be ramshackle to a degree that exceeded even their bedraggled reputation, and recording an album that would prove – with an irony which clearly delighted Young – too lo-fi and grungy for the grunge generation.

Shortly before Briggs died on November 26, 1995, Young went to visit him in San Francisco. In Waging Heavy Peace, he recalls asking Briggs – possibly his one equal as a curmudgeon – for “any advice for me on my music going forward?”

“Just make sure to have as much of you in the recording as you can,” Briggs apparently instructed him. “Stay simple. No one gives a shit about anything else.”

“He told me to keep it simple and focused,” continues Young, “have as much of my playing and singing as possible, and not to hide it with other things. Don’t embellish it with other people I don’t need or hide it in any way. Simple and focused. That’s what I took away. He didn’t exactly say that, but I got that message.”

It’s a telling insight into Young’s single-mindedness that he asked Briggs for guidance, but acted on his own interpretation of what was said, rather than the producer’s specific instructions. His first move in 1997 was to call Ralph Molina, Billy Talbot and Frank Sampedro back into service. To reconnect to their essence, Crazy Horse embarked on a series of spring gigs way below the radar, including a string of 14 nights at the Old Princeton Landing, a 150-capacity venue close to Young’s Broken Arrow ranch in Northern California. At the same time, the quartet started jamming out a new album back at the ranch, in the studio space named Plywood Analog.

Broken Arrow, as it turned out, certainly captures the spontaneity of the project. The opening sequence of three longish pieces – “Big Time”, “Loose Change” and “Slip Away” – give credence to Young’s assertion that “it’s all one song”, and even though the album toys with different styles in its second half, there’s a rumbling, meditative intensity throughout that the seemingly sloppy playing cannot derail.

What some might call meditative intensity, of course, others would describe as lethargy. “Big Time”’s lyrics contain what sounds like a pledge to continue Briggs’ vision – “I’m still living in the dream we had. For me it’s not over” – but it is delivered not with vigorous defiance, but at a trudging pace which suggests the exertions of the early ‘90s left Young somewhat exhausted. Crazy Horse are at their most truculent and unstable, with Molina especially idiosyncratic in his approach to keeping time, and even Young’s solos begin by sounding a little tentative. As the song lurches on, though, and Young overdubs a plinking one-note piano line, “Big Time” gradually builds in heft – if not achieving resolution, at least setting the mood for much of Broken Arrow. Young’s vocals are often so frail and mixed so low, notably on “Slip Away”, that he sometimes collapses into the woebegone harmonies of his bandmates. But, beneath the brusque treatments and raw production, these are insidious and strange songs, far better than their reputation promises.

The key moment, perhaps, comes about three and a half minutes into “Loose Change”, when the song’s battered vamp devolves into an abstract, locked-groove churn that suggests more lessons may have been subconsciously learned from Sonic Youth on the Weld jaunt. While Young carves out a few brutal, glancing solos, Crazy Horse get stuck on a single-chord cycle. Dogged and inexorable, they grind on hypnotically for another six minutes towards unlikely transcendence. According to Jimmy McDonough in Shakey, “When Sampedro’s girlfriend asked why the band got hung up on the chord for so long, he said, ‘We were playing David on his way.’”

After the similarly gusting “Slip Away”, Broken Arrow becomes more fragmented. “Changing Highways” is an amiable enough barn-raiser with a passing resemblance to “Are You Ready For The Country”; “This Town” an odd, whispered, mostly unmemorable chug. “Scattered (Let’s Think About Livin’)”, though, is a genuinely great song; a Briggs elegy with a see-sawing riff (kin to “Old Man” and “Albuquerque”, perhaps) and Young essaying a message of vague spiritual hope (“When the music calls I’ll be there/No more sadness, no more cares”) in the most deflated tone imaginable.

“Music Arcade”, meanwhile, is a fittingly ghostly kiss-off: Young alone with his acoustic guitar, talking about being lost, being found out and being prepared to move on. After the fecund run of ‘90s albums, with hindsight the song feels like a farewell to the business for a while. Following six new albums in six years, his fans would have to wait until 2000 before Young resurfaced with Silver & Gold.

“They’ll shit on this one,” Young told McDonough, pre-empting the critical response to Broken Arrow. “I’ve given them a moving target – there’s enough weaknesses in this one for them to go for it… It’s purposefully vulnerable and unfinished. I wanted to get one under my belt without David.”

To end with “Music Arcade”, though, would be too neat. On the vinyl edition, he tacks on “Interstate”, a magnificent outtake from Briggs’ Ragged Glory sessions, with an intricate, almost classical, guitar line, and a vocal that puts the worn-out timbre of Broken Arrow into startling perspective.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_xErYIU148k

And on one of his most untidy albums, Young has one last exasperating trick. “Baby What You Want Me To Do” finds Crazy Horse loping artlessly through an old Jimmy Reed blues, recorded on an audience microphone (the whoops and chatter are mostly louder than the group) at one of the Old Princeton Landing shows. Just another bar band, it seems, playing for love, a few beers, the memory of an old comrade, and the enigmatic whims of their leader.

Follow me on Twitter: www.twitter.com/JohnRMulvey