Despite the stage name and visual reinventions accompanying each new album, Bat For Lashes has never been a persona. Instead, it’s a vessel for the intimate songs of Natasha Khan, the British songwriter who grounds her musical flights of fancy in stark examinations of heartbreak, home and self-realisation. Yet critics have often overlooked her acuity as a songwriter; distracted by her spiritual adornments and uninhibited art school sensibility, there’s a dispiriting tendency to marginalise her as a kook, and to wish she would strip away the fuss so that we could hear her better. After all, confession is still considered the strongest currency of women’s art, and female musicians playing with image and identity are rarely afforded the credibility of, say, Father John Misty.

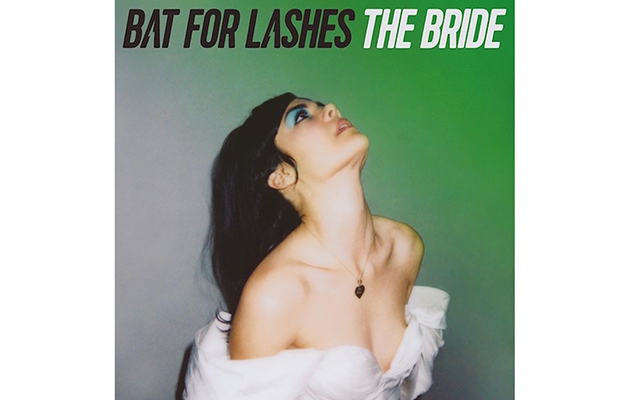

“Come out, show yourself,” comes the demand, “submit to verdict and discipline,” Slate music critic Carl Wilson wrote of this desire, in an astute piece comparing Joanna Newsom, country singer Iris DeMent, and Italian author Elena Ferrante, women who he wrote were “performing a vanishing act in order to be seen.” On The Bride, Khan joins their number. Her fourth full-length as Bat For Lashes is a complete concept album, where she plays a woman whose groom dies on the way to their wedding. Ravaged by grief, she hijacks the honeymoon car and drives off into what becomes a journey of self-discovery. By the end of the record, the bride wouldn’t trade the knowledge she’s acquired for a different outcome. In interviews, Khan has evaded being drawn on the story’s personal significance.

The narrative arc makes The Bride feel even more like a close relative of Newsom’s Divers, using impersonal narrators to reckon with the prospect of true love, which “invites death into your life,” as Newsom told Uncut last year, while both attribute agency to women’s stories. Khan’s protagonist gets free, escaping the definition of marriage and widowhood by setting off on the road, a path rarely trodden by fictional women. “A man on the road is caught in the act of a becoming,” observed Vanessa Veselka in an essay on the lack of female narrative quests for The American Reader. “A woman on the road has something seriously wrong with her.” By setting her bride out of bounds, Khan rebukes both that idea, and perceptions of the female auteur-as-diary-writer, emphasising the distance between herself and her art, which has seldom sounded stronger.

Each of Bat For Lashes’ albums to date have contained half a dozen or so spectacular songs, usually the pop numbers. Although she received widespread critical acclaim from 2006 debut Fur & Gold through to 2012’s The Haunted Man, there was the sense that she hadn’t yet made her first truly great record. The Bride is it, despite playing against Khan’s pop strengths in favour of midnight torch songs that echo This Mortal Coil, later-period Radiohead, and ’70s AOR. There’s one uptempo song here, “Sunday Love”, where the bride is haunted by what could have been, her anxiety echoed by a corroded drum machine. It’s heart-racing, affecting stuff, especially as the distance opens up between its bassy depths and the transcendent heights of Khan’s vocals. But the rest of The Bride eschews such overt pop signifiers to foreground the subtlety of Khan’s melodies, and her voice’s expressive power, emphasised by the cinematic production: fathoms of nuanced bass and subtle synth beds that offer a forest’s eerie enveloping.

These qualities push The Bride beyond being a concept album and into an emotionally resonant record that works regardless of your investment in the story. There are a couple of exceptions: opener “I Do” finds Khan pledging her faith in wedded bliss, to bright autoharp trills that glint like sunbeams. It’s overly naïve, but justified to set up the story, and brief at any rate. That can’t be said for “Widow’s Peak”: a torrid spoken word interlude haunted by thunderous crashes and distant cries. It disrupts the album’s flow, and feels hammy compared to the easy grace on show elsewhere, which is quite majestic. Her story starts as dynamic balladry that eschews both melancholy and sentimentality for something ominous and grave: the swaggering, Morricone-indebted guitar of “Joe’s Dream” buoys a sweet Greek chorus, meanwhile “In God’s House” is the desolate terrain in which Khan confronts her loss in quasi-operatic tones.

Perhaps it’s a result of fronting Sexwitch last autumn, a collaboration with London psych band Toy where the newly minted group covered obscure pop and folk songs from Iran, Morocco and Thailand. At those shows, Khan howled and screamed; The Bride isn’t as visceral, but her range has opened up enormously. She’s flinty and suspicious on “Honeymooning Alone”, matching the pace of the stalking guitar, before opening up on the chorus, surrounded again by a sweet, girlish choir. On “Never Forgive The Angels”, the force of her voice pushes the song’s meditative drone heavenwards. The record’s standout is “Close Encounters”, a surreal folk song about a metaphysical interaction comprising just ghostly strings and Khan’s reaching vocals.

The rest of the album plays out like this: simple songs featuring Khan’s voice amidst a subtle landscape. With its gentle, lilting guitar and silvery violin, “Land’s End” is tentatively optimistic, while the romantic piano and comfortably AOR chorus of “If I Knew” plays like the pragmatic cousin to The Carpenters‘ “We’ve Only Just Begun”. The melodies at this end of the record are as accomplished and affecting as Bacharach and David songs, as Khan’s bride emerges into the light: “I will turn it back around/I’ll be homeward bound,” she declares on “I Will Love Again”, which balances her tentatively hopeful sentiment with a steady pulse and enveloping strings. And “In Your Bed” is cinematic and romantic; a realistic update of “I Do”, where deep connection is prized over salvation.

It’s a fitting ending: Khan’s fourth album is a mature piece of work, but doesn’t forsake her infectious, wide-eyed enthusiasm for the possibilities of her art. She’s hoping to turn this story into a book and a feature film. Whether those transpire or not hardly matters; The Bride is her most accomplished realisation of her wandering mind yet.

Q&A

You’ve said this album feels like coming home to yourself. What allowed that to happen now?

It’s mysterious really. I suppose there’s an aspect of developing confidence after doing this for a decade, or having tried so many other things out in the world. It’s like a relationship – you fall in love in so many different ways, and then sometimes 10 years later you find you’re having just as romantic a period as when you first met.

You performed almost the whole record in churches pre-release. How was that experience?

Amazing. Coming down the aisle with my bouquet and throwing it into the crowd, everyone sitting so quietly and listening because they were no-phone shows, huge stained glass windows, playing in sacred spaces that have this really heavy weight of history – it couldn’t have been better. It added to the melodrama and theatricality of the storytelling.

Walking down the aisle night after night and then singing “I Do” alone seems like a heavy experience.

Yeah, it’s really nerve-wracking and very emotional. Every time I’ve done it, I’ve felt like crying, and then when I get onto the stage, I have to really gulp and compose myself. It’s very exposing and very vulnerable, but I think that’s what makes it so beautiful because I feel like I’m really putting myself out there, trusting the audience. There’s this collective enjoyment of being in a really vulnerable place, and I think vulnerability is really underrated nowadays.

At the start of The Haunted Man, you were creatively blocked. But with this album – and the accompanying film, imagery, and a potential book – it seems you were in a very creative place.

I feel like it was the first time where I was really taking seriously my need to work on multidimensional levels, and that I can’t just narrow myself down to being a musician, putting out an album, doing a tour, coming home, starting again. I wasn’t able to express all of the avenues and facets of what I want to do in that cycle. There was a change in myself, and a change in my understanding of what’s expected of me and what I want to do, putting my process at the forefront and then just really enjoying swapping between all these different media.

There’s quite a few Americana artists on the record – Simone Felice, Dawn Landes. Any significance to that connection?

It wasn’t the genre so much but the people. I knew I wanted to play more guitar, and then I wanted more guitar textures. I’ve known Lou [Rogai, Lewis & Clark] for eight years, we’re really old friends – he and Eve Miller played with Rachel’s, who I used to absolutely love when I was at uni. I thought of him as someone that’s really textural. Dawn I’d seen playing with Sufjan Stevens, so I guess she is folky, but I asked her because I loved her voice and playing when I saw Sufjan doing Carrie And Lowell, so maybe there was a bit of that.

You had a six-week recording session in Woodstock. How did the atmosphere fuel the record?

The rainy pine forest, Twin Peaks vibe was really magical and really infused the music, I think. I felt it was the closest landscape that linked to the landscape I could imagine in parts of The Bride.

How much of a political comment is there in there about societal expectations of women?

I’ve softened on that the more I’ve talked about it. What’s so beautiful about the album is towards the end there’s this thankfulness and this great gratitude to the bride’s dead fiancé for standing by her side through this journey of self-discovery and learning to really love yourself. I think that it was through him making her stand on her own two feet that she was able to get to the end – songs like “If I Knew” and “I Will Love Again”, where she realises how unconditional love from another person can really heal you and help you to find a space in yourself where you’re not looking to an external source to rescue you. By the end it’s the greatest love of all, which is this really poignant kind of companionship that she’s developed with him even though he’s not there in his physical form. He’s loved her to the point where she’s ready to really love someone in a real way, and so the album is about setting yourself up to really love someone. It is pro-relationships and pro-companionships and love, but it’s anti-overly romanticised, idealistic, and quite scary codependent ideas about love, which I think we’re sold quite shamelessly in films and media.

INTERVIEW: LAURA SNAPES

Uncut: the spiritual home of great rock music.