Watching Allen Toussaint late in his career, after his post-Katrina collaboration with Elvis Costello, The River In Reverse, finally legitimised him as a solo performer, he cut a warm-hearted, gentlemanly figure. Lacking a star’s ego or showmanship, he amply compensated with impish charm and eccentric wit. His mild, modest voice barely brushed his songs, and he amiably acknowledged his own albums’ negligible appeal next to the hits he wrote, produced and arranged for fellow New Orleanians Ernie K-Doe (“Here Come The Girls”), Irma Thomas (“Ruler Of My Heart”), The Meters (“Look-ka Py Py”) and Dr. John (“Right Place, Wrong Time”). He was in his element at the piano, hands skipping and flicking the keys in second-line style, priceless pop history reaching back to Professor Longhair at his fingertips.

Watching Allen Toussaint late in his career, after his post-Katrina collaboration with Elvis Costello, The River In Reverse, finally legitimised him as a solo performer, he cut a warm-hearted, gentlemanly figure. Lacking a star’s ego or showmanship, he amply compensated with impish charm and eccentric wit. His mild, modest voice barely brushed his songs, and he amiably acknowledged his own albums’ negligible appeal next to the hits he wrote, produced and arranged for fellow New Orleanians Ernie K-Doe (“Here Come The Girls”), Irma Thomas (“Ruler Of My Heart”), The Meters (“Look-ka Py Py”) and Dr. John (“Right Place, Wrong Time”). He was in his element at the piano, hands skipping and flicking the keys in second-line style, priceless pop history reaching back to Professor Longhair at his fingertips.

Toussaint was an “oblique character”, a visitor to his studio observed in 1974, as he made his fourth stylistically varied attempt to record his best-known album, Southern Nights, gripped by uncharacteristic uncertainty when he turned his A&R talents inwards. “I try to write songs according to how I visualise their personality,” he said of his other clients, yet he struggled to apply the process to himself. “I don’t respect my voice,” he confessed. “Some of the things I write for myself just don’t feel like me when I sing.”

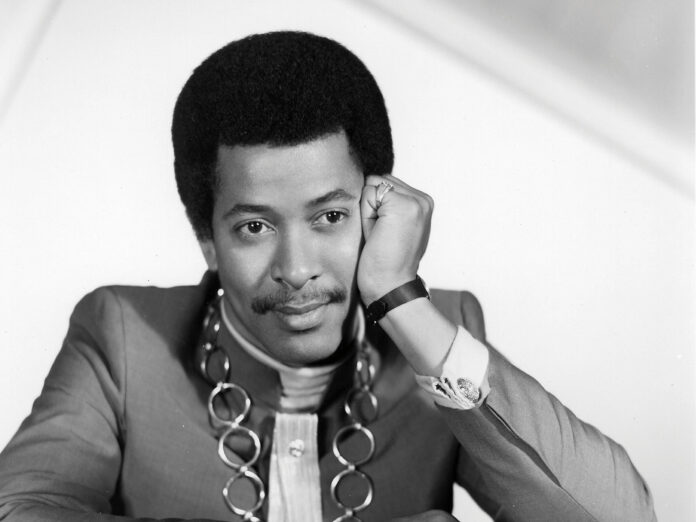

Toussaint was therefore 32 when he reluctantly recorded his debut as a singer-songwriter in 1970, following 1958’s instrumental The Wild Sound Of New Orleans. The sleeve closely framed his face, and the album was called simply Toussaint in the UK (and From A Whisper To A Scream in the States), as if this music defined him. Like the rock assignments after groups heard his thrilling horn charts on The Band’s Rock Of Ages and the long major-label deals he signed himself and The Meters to directly after Toussaint, his main motivation in this period centred on financing New Orleans’ first modern studio, aiming to resurrect the languishing scene and musical heritage of the city he served his whole life. Personal ambition and lyrical expression were secondary. Yet Toussaint clearly reflects his character, and draws deeply on his studio genius.

“From A Whisper To A Scream” coalesces from ticking drums and Dr John’s organ pulse, with backing singers including Merry Clayton enacting both the “whisper” and “scream”. Toussaint’s voice floats over his subtly balanced arrangement, guitar notes curling as if in sultry heat, as he realises he’s lost his girl to another, ’til the gospel vocals’ chiding hum concludes the lesson. Toussaint’s persona in the next song remains that of the male romantic loser, a blues as much as soul trope. “Chokin’ Kind”, a country song by Nashville’s Harlan Howard which Louisianan Joe Simon made an R&B chart-topper, sees Toussaint unable to handle love that “scares me to death” over a restless, syncopated beat. “Sweet Touch Of Love” finds romance’s “cold chill” reach him at last, in an ebullient song bolstered by triumphant brass, surging guitar and his own lugubrious piano.

“What Is Success” switches into another Toussaint blues mode, the suffering American working man, here wrestling with crushing pressure for financial success over a more idealistic life: “How does one decide, that the methods he’s using, they just won’t jive?” The realist lyric is built on wryly propulsive bass and piano and ironic harmonies, a form of R&B emerging directly from Toussaint’s urbane, amused intellect. “Working In The Coal Mine”, his 1966 hit for Lee Dorsey, similarly finds fatalistic humour and bustling life in exhaustedly “hauling coal by the ton”. It’s as much a message song as “Maggie’s Farm”, couched in irresistible, up-tempo momentum matching its subject’s pickaxe. “Everything I Do Gonna Be Funky” is a greasier assertion of self-worth, with scratchy, country slide guitar. Toussaint’s drawling New Orleans accent and abstractedly self-absorbed vocal style embody the music’s languid, liberated sense of being “the natural me”.

The four concluding instrumentals are the most direct route to Toussaint’s heart. Laying his onerous vocal responsibilities down for almost half the album raises the white flag for solo ambitions, from one perspective. But it also completes the self-portrait of a curious New Orleans soul as intrigued by Monk and Debussy as Fats Domino. “Pickles”’ ambling group R&B showcases a classical piano solo of romantic glissandos and introspection. “Louie” is a sunnier stroll, “Either” a sly soul strut. The sleeve credits Vince Guaraldi’s 1962 jazz hit “Cast Your Fate To The Wind” to “Allen Toussaint at the piano”, and his joyous R&B lope, stabs and vamps are still rolling at the fade. Abandoning the singer’s public-facing career, this is the private Toussaint, letting us know how it feels for him to be free.