http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zv4Lkgx6oW0

Invariably seen cavorting around onstage in the flimsiest lingerie, Prince’s stunning protégée Vanity is described by screenwriter William Blinn as “the most gaspingly beautiful woman I’ve ever met”. Vanity’s decision to pull out of Purple Rain – after a disagreement about personal terms – created a casting emergency. After frantic auditions in Minneapolis, New York and LA, a replacement was found in Apollonia Kotero, a sweet-looking girl with a cute smile. While she provided the love interest, and Morris Day and sidekick Jerome Benton had fun as pantomime villains, Prince smouldered and scowled, a tortured soul with dilemmas everywhere. The man could act. But it was the scenes shot in the nightclub that made Purple Rain so memorable.

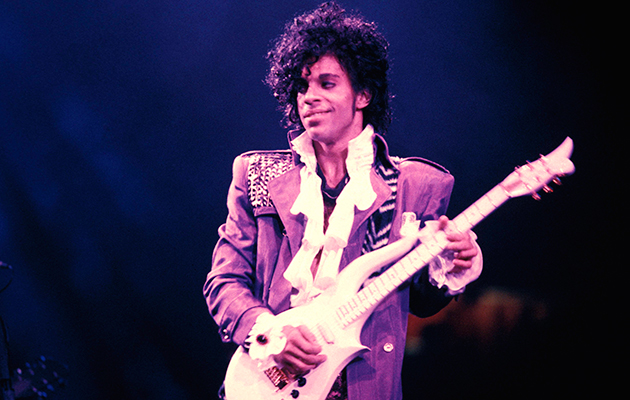

“It was the only time that Prince questioned the filmmaking process,” Magnoli relates. “He wasn’t used to stopping and starting the music while the cameras were realigned. He said, ‘Why are we stopping? I can’t do this!’ I came up with the idea that we’d do the performance all the way through, but then he’d give me a Take 2 and a Take 3. We were using four cameras per take, so that gave me 12 different angles and Prince could stay in performance mode, which he liked.”

“It became clear that the nightclub footage was going to carry the movie,” remarks Alan Leeds. “It wasn’t a popular thing to say out loud, because Prince wanted to believe that he was creating some form of magic theatre. But the performance scenes are what did it. They were so uniquely lit and shot. They made people feel like they were at a concert.”

Warners Bros, after their initial doubts, had been persuaded to invest. With the production running over-budget and requiring an urgent cash injection, the studio’s president, Terry Semel, asked to see a rough edit. But Magnoli had not yet edited those vital nightclub scenes.

“We show them the assemblage,” recalls Cavallo. “Semel stands up and says to Mo Ostin [chairman of Warner Bros Records], ‘Well, Mo, looks like you’ve given me another one of your rock fuck-ups.’ He’d been burned on Paul Simon’s One Trick Pony and was blaming Mo for what he was sure would be another failure.” Other Warners executives were more upbeat. Magnoli heard someone say “it’s a smash”. $600,000 was forthcoming.

Magnoli: “Then we finished it and there were discussions about to how to market it. The suits at Warners felt that I’d made a movie for an urban audience, meaning 13-year-old black girls, meaning the film probably only had a weekend or two at the box office. I said to them, ‘Do I look like a 13-year-old black girl? You’re dead wrong and I don’t give a crap what your research is telling you.’ The conversation made no sense to us. So we decided to screen it to white audiences.”

Cavallo: “The first screening was in Culver City, and Warners thought I’d set the audience up. They thought I’d put the Prince fan club in there! Semel said, ‘Bob, this is the film business. You’re not hyping a radio station.’” Warners deliberately kept the location of the next screening a secret. “So we got to this mall in a suburb of Denver,” recalls Cavallo and there’s a riot going on. The kids outside are going nuts – there are way more of them than the theatre has room for. The theatre owner has to beg for a couple more screenings. By now Warners know they’ve got something.”

Magnoli: “They realised, ‘Holy crap, the screenings are going way off the charts.’ And that’s when the suits stepped up to the plate and got us 900 theatres to open in. That was the first week. Then it went up to a thousand.”

Purple Rain officially premiered at Mann’s Chinese Theatre in Hollywood on July 27, 1984. Eddie Murphy, Lionel Richie and Pee-wee Herman were among the A-list celebrities in attendance. Prince arrived in a purple stretch limo, distractedly holding a flower, unable to believe the size of the crowds. At the opening in Detroit days later, one of Prince’s promoters happened to be in the audience.

Alan Leeds: “He phoned us saying, ‘You won’t believe what’s going on. It’s like The Beatles. They’re screaming so loud you can’t hear the dialogue.’”

Cavallo: “Everything worked. The movie did $68 million, they say, in the first 12 months. Personally I always thought it was $70 million, but who’s going to argue? ”

Magnoli: “It was a different time. The major studios didn’t have their strategies locked down. Nowadays, of course, we would have been signed by Warners for a series of Purple Rain sequels in, like, 10 seconds. But back then it was, ‘Well, what do we all do now?’”

There was only one man who could kill Purple Rain’s momentum, and he did it on April 22, 1985 when he released Around The World In A Day, while Purple Rain was still selling steadily. His managers warned him that his timing was awful – for one thing, they were anxious to avoid market fatigue. But Prince, superstar, A-lister, autonomous will-o’-the-wisp, had entered a new phase of total artistic non-flexibility. Having heeded none of the warnings, his half-baked 1986 movie, Under The Cherry Moon (which he directed), won Golden Raspberry Awards for Worst Actor, Worst Director and Worst Film – in a tie with Howard The Duck. No purple stretch limos were spotted in the area that night.