This article originally appeared in Uncut Take 187 (December 2012)

Ask Kris Kristofferson how he’s doing and he chuckles. “Pretty good, pretty good… pretty old.” At 76, the country legend certainly has plenty of life to look back on. Kristofferson had already been a Rhodes scholar, an army captain, a janitor at Columbia’s Nashville studio, a helicopter pilot and a killer songwriter before finally becoming one of the biggest recording artists and movie stars of the 70s. Revealing a muse still in fine fettle, his new album Feeling Mortal is a reflective affair, and Uncut finds him happily inclined to cast an eye over his numerous achievements. “Songs are just like your kids,” he says. “You love them all and they’re all different. I can’t really pick out favourites.”

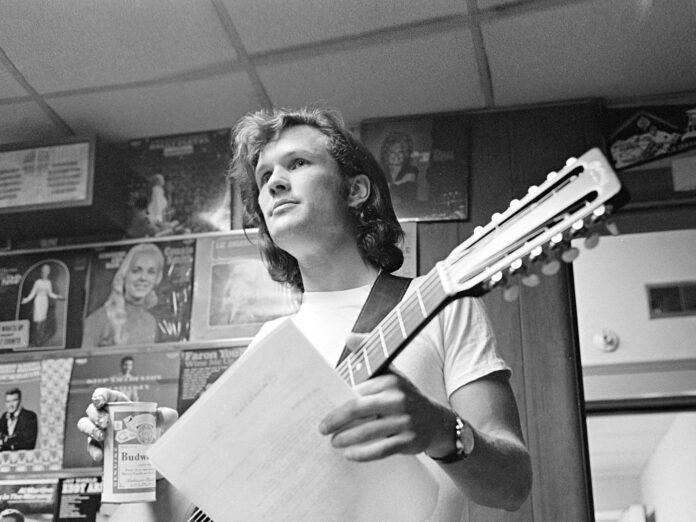

KRIS KRISTOFFERSON

Kristofferson

Monument, 1970

Already 34, Kristofferson releases one of the great debut albums, a record crammed with timeless songs, many of which had already been hits for others – or soon would be…

I’d had five years of being in Nashville where they didn’t even want me to sing my own demos! I got other people to sing them for me, but then my publisher couldn’t afford to do that any more so I had to sing them myself. But Fred [Foster] at Monument decided I was a singer-songwriter, so I followed his advice and did it. I’m sure there were people who wondered why in the world I thought I would make it as a singer, but it was something I loved, whether I was built for it or not. And it worked out. Everything was working magically. Johnny Cash was my friend and was doing my song, “Sunday Morning Coming Down”, and suddenly everything seemed to be turning out for the best.

The album is quite produced. I probably wouldn’t record it the same way now, but at the time I felt they were making the songs sound better than they were! I’m lucky that I got to put as much of myself into this record as I did, because country music still wasn’t as wide open as it is now. It didn’t change overnight, it was a slow process. Bob Dylan was the guy who changed it all. Dylan’s relationship with Johnny Cash was the biggest influence on Nashville in my lifetime – they opened up country music. Dylan was the ground breaker we all benefited from, and Cash met him halfway. The next thing you know we started writing as freely as Bob was. I was suddenly aware that the soulful part of the songwriters in Nashville that I identified with would eventually prevail.

There were so many different ways we were trying to do it. I would demo something at night by myself over at the publishing house and get Billy Swan and Donnie Fritts to sing harmony. We did “Me And Bobby McGee” that way. I remember Billy saying, “Man, this feels real spiritual, like ‘Hey Jude’”! We loved the feel of it so much. I knew it was a good one; sometimes they’re keepers and sometimes they’re not. I can remember writing “Help Me Make It Through The Night” in the Gulf of Mexico. It was pretty lonely work out there and it came real fast.

I still sing just about every one of these things. I haven’t done “Blame It On The Stones” or “The Law Is For The Protection Of The People” in a while – all the others, I’m embarrassed to say, I’m singing all the time. But performing them still feels creative to me. They’re things that I can believe in.