Everyone knows the mythical image of The Man In Black. But the truth about Johnny Cash was a whole lot more complicated. A “folk hero for the world”, and a humble man who struggled with addiction for his entire life. In this archive feature from Uncut’s February 2009 issue (Take 141), we present a revelatory new portrait of Cash’s life. We talk to many of the people who knew him best – the children, the bandmates, the managers, the peers – and discover the unexpurgated truth about this titan of American music. “He survived,” says his one-time son-in-law, “what Elvis didn’t…” Words: Alastair McKay

_______________

“My dad lived with pain his whole life,” says John Carter Cash of the father whose legend he for many years struggled to both live with and up to. “It was partially the way he was made, and partially the pain of addiction, and partially the loss of his brother when he was younger,” he continues, referring to the horrific death of Jack Cash, Johnny’s older brother, who Johnny saw cut almost in two in a sawmill accident in 1944. “His greatest pain was interior pain. But in the last 10 to 12 years of his life, physical pain took over. And you don’t triumph over physical pain.”

Johnny Cash’s physical traumas were legion, and were subject to a bewildering range of diagnoses, from diabetes, to Parkinson’s disease to Shy-Drager syndrome, a degenerative disease of the nervous system. He also had chronic nerve damage in his jaw.

“Every day of his life he dealt with some sort of physical pain,” says John Carter, “and for the last 10 years, he was an abusive addict for the most part. He never stopped using substances.”

This contradicts the traditional view of Cash’s life, as told in James Mangold’s Oscar-winning 2005 biopic, Walk The Line, which turned the fiery ring of Johnny’s love affair with his second wife, June Carter Cash – formerly a member of the legendary Carter Family, true country royalty – into a Hollywood parable. The myth has it that June saved him from a life of drug dependency.

“That’s a good story,” says Rosanne Cash, Johnny’s daughter by his first wife, Vivian. “Woman rescues man from the abyss, and comes back from drugs, and they live happily ever after. It’s nice and neat and clean and people can understand it. The truth is a lot more complicated. The truth is my dad struggled with addiction for the rest of his life.”

“There’s an image that my mother saved my father in 1968 and everything was a bed of roses after that,” says John Carter. “And that just wasn’t true. There were as many struggles in the 1980s and the 1990s as there were in the 1960s. They were just different drugs. But my father always went back to what was true, and he would turn his suffering around. He learned from his lessons. But the very nature of addiction is that the addict is incorrigible. And my dad dealt with it all his life.”

“He lived hard,” says Rodney Crowell, the singer-songwriter who was married to Rosanne, and played in Emmylou Harris’ Hot Band. “He wore himself out. He struggled with a lot of demons. That was a part of John I was aware of. He had currents swimming in different directions. He struggled with drugs most of his life. There was that clean-up time, which he really had, that big turnaround with June, but he still struggled later on.”

What was at the root of the drug problem? Was it a recreational thing that spiralled out of control?

“No,” says Crowell. “It was more like he survived what Elvis didn’t survive. I talked to him about this. When they came of age, John and Elvis and people like that, when they were coming through, those guys were making records and going on the road and trying to keep their schedule together; and somebody would hand them amphetamines, which is basically like plugging yourself into the light fixture. We talked about this. They handed those guys the hard stuff from the get-go. At least when I came up, people were handing you a beer and a joint. It was a gentler entry into that world.

“For those guys coming up in the ’50s – the Everlys and all those guys – they handed them amphetamines. Scientifically, there are those who are pre-disposed to struggle with introducing chemicals to their body. And you’re in for a long bout with that: amphetamines are rough. When you’re flying on it, it’s like you can conquer the world, but coming down off it’s a really hard crash.”

“I loved him to death,” says Marshall Grant, bass player of Cash’s original band, The Tennessee Two and a lifelong friend. “But I would want to stomp him into the ground sometimes when he was on the pills. He was such a great man, such a great artist, but they just overpowered him. He could not go without them. He loved those little pills. And it never was the hard stuff, the cocaine and all that crap like that, it was those little pills. That was all he wanted.

“The instant that John Carter Cash was born, which was March 3, 1970, he went off of ’em, just totally,” Grant says. “Quit smokin’, lived a clean life, started going to church. Then the drugs came back. And when they came back, the end result is laying out in the cemetery in Hendersonville, Tennessee. By then, he’d destroyed every vital organ in his body. It’s a long, hard, sad story.”

_______________

Memphis, 1954. Marshall Grant, Luther Perkins and Johnny’s brother, Roy Cash, are working at Automobile Sales Co on Union Avenue, along the street from the Sun studio. Roy introduces Grant and Perkins to his brother John, fresh from his national service in Germany and newly married to Vivian Liberto. The trio audition at Sun for Sam Phillips. Their first inclination is to play gospel, but Phillips tells them there’s no market for it and tells them to come back with original material. Cash returns with a poem, which becomes “Hey Porter”, which becomes his first 45. The second is “Folsom Prison Blues”. “Our third single was a song called ‘I Walk The Line’,” says Grant, “and it went straight to No 1 Country, No 1 Pop, and No 1 Rock’n’Roll. It’s what Sam called a triple crown.”

This meteoric success was hard-earned. Pretty soon, Cash and The Tennessee Two were launched onto a gruelling schedule, driving themselves to 250 dates a year on their way to becoming one of the biggest acts in country music. Did success change Cash?

“Success didn’t change John,” says Grant. “He stayed very humble. He stood very thankful. The only thing that changed John, early in our career, these little pills came along. That changed him a bunch. But as far as success, that didn’t change him. He stayed the same JR. We all called him JR or John. I never called him Johnny in my entire life. It was the pills that created a lot of problems.”

Does Grant remember when Cash first started using amphetamines? He does, vividly: “In 1956, we came out of Texas, and drove all the way to Columbus, Georgia. We were opening for [Honky Tonk star] Faron Young. We’d driven all night and all day. John, Luther, myself and Faron Young’s fiddle player, Gordon Terry, were standing on the side of the stage getting ready for our introduction. And John said, ‘I’m so tired, I don’t know if I can do this or not.’ I said, ‘Well, God knows we’ve been tired before, we can do it.’ Gordon turned to John and said, ‘Wait a minute.’ He reached in his pocket and pulled out some innocent-looking pills… they looked like aspirin. And he handed John about six of them, or four, I didn’t count. And he said, ‘Here, take these, and you’ll make it through the night with no problems.’

“So John got a glass of water, took those pills. He was still tired at that point, but after he went on stage you could see him change – those pills were taking effect. And it made a different person out of him. He was jumping around, feeling really, really good. Well, he got some of those little pills from Gordon, and he took them.

“At this point he only took them when he felt he needed them. But as time went along he felt that he needed them more often, and then they started changing him. They were in his system all the time, and he was a totally different person. He didn’t have much respect for anybody, or anything, and so it just got worse. And worse. And it got as bad as it could get and then still got worse. And he loved those things. He absolutely cherished them. He loved them like some people love a brother.

_______________

Johnny Western has a vivid memory of the first time he heard Johnny Cash. Western, who played guitar for singing cowboy Gene Autry, was driving down the Hollywood freeway listening to a country station when the DJ played “Folsom Prison Blues”.

“I almost wrecked my car. I got into that beat and I started imagining what that man with that very masculine voice must look like. I thought: ‘He’s gotta be over six feet tall, with jet-black hair.’

“Well the first picture I ever saw of Johnny Cash, he looked exactly like I thought he would, and he had that big hole in his cheek where he had that cyst cut out, and he looked like he’d been hit in the face with a ring. But that massively great looking face was there. And that’s the way he looked for the rest of his life. As he aged and got more lines, and beat up his body, he became this American folk-hero type – a folk hero to the world.”

Western fell into Cash’s orbit in 1958, when Cash moved to LA, with the intention of making an impact in Hollywood. Grant and Perkins went with him, but unable to settle promptly returned to Tennessee. Western was hired to assemble the Johnny Cash stage show. He toured with Cash from November 1958 to October 1997.

“In the beginning he was terrific because he was as straight as a string,” Western says. “The most he would drink was maybe a half a beer. He did smoke. But that was as far as any addictions went. He was so much fun to be around – he was up all the time.

“As time picked up, the amphetamines started to take over and he started changing personality. You wouldn’t know if he was going to talk to you, on or offstage. Other times he couldn’t get enough of talking. It was a real Jekyll and Hyde type thing.

“When Elvis died, he had about 10 different drugs in his body. And when Johnny died, there were just massive amounts of drugs that he’d taken in previous years that had destroyed his body. Amphetamines and then all kinds of downers he’d take so he could sleep for 18 hours. That’s what they call the Rainbow Effect, where you’re so high for so long, you have to physically knock yourself out with sleeping pills and downers to get some sleep.”

Western says there were several times when the band feared Cash had died.

“We couldn’t even get a pulse on two or three occasions. But he always had the stamina to come back, and run a doctor over there to give him a B12 shot. A couple of times he missed the matinee shows, but even on the worst of occasions, he made the night show. He might go weeks and be fairly straight and be so much fun to be around, then these pills would just hit and he would disappear.”

Cash was not the only one who contracted road fever. “Marshall had a small Black & Decker circle saw,” says Western, “and he started cutting up the furniture in hotel rooms, and putting it back on these angles, blowing all the dust away so that when we checked out of the hotel and the maids would come in, they’d hit the furniture with a duster and the whole room would fall apart. We had a lot of hotels we couldn’t go back to any more.

“When Johnny was really pilled up once, in one big motel, Carl Perkins was staying in the next room, but there was no dividing door between the rooms, so he took a metal chair and smashed the wall down so they could walk back and forth. That cost a couple of thousand dollars. We were doing stuff that Mick Jagger and those guys picked up on later on. It was just that kind of a lifestyle.

“You gotta realise he was taking up to 100 pills a day. The body resistance had been built up. Had anybody else attempted to take even half that, it woulda killed ’em. It woulda knocked ’em straight to their knees and killed ’em. But his body had been absorbing all these tablets for so long, the tolerance level was just incredible. He would just get completely out of it. He would end up in hotels and motels back in the hills someplace. One time, he borrowed my brand new Cadillac and he was so far out of it on pills, he lost it in Hollywood. He called me sheepishly when he sobered up and said, ‘Johnny, I lost your car. I was just going to borrow it for two or three hours and I think I left it down at the Farmer’s Market’ – this place that was open 24 hours a day – ‘but I can’t remember. Right now I’m in a motel on the other side of Beverly Hills and I don’t know how I got here. I guess I got a cab.’ He was just really out of it at that time.”

Sometimes Western and Cash would drive out into the Mojave Desert in his Mk IV Jaguar, and talk: “His marriage was falling apart. He was falling in love with June and she still had a husband and he still had a wife, and both of them had children.”

_______________

Cash’s first wife, Vivian, was Catholic, and reluctant to get a divorce. June’s husband, Rip Nix, a failed Tennessee footballer who became a Nashville cop, was living off her and refused to kiss his meal-ticket goodbye.

“He had offered Vivian a million dollars to let him go when he was totally in love with June Carter,” says Western. “But June couldn’t get away from this Rip Nix. He threatened to drag her and the Carter Family through every mud-hole in Tennessee. That scared the heck out of her, and then seeing Johnny in the shape that he was in… but he was in a lot of that shape because of her, because he could not marry her. The amphetamines were like a comfort zone, so he could blast his way out of it.

“She finally did divorce Rip Nix and he got that divorce from Vivian. Oddly enough John had offered her a million dollars to get out of that marriage, and by the time the judge got done, he awarded Vivian exactly half of that.

“June was a kind of saviour. She and Marshall Grant saved his life as far as flushing those pills down the toilet and trying to keep him straight. He hated them both for doing it. They became his worst enemies, because he loved those pills. When he sobered up, he’d be sorry for the whole thing. But he would do it again. And again, and again, and again. So they had a very tumultuous relationship through their entire marriage.”

“We had no allies whatsoever,” says Grant. “Everybody else just thought he was funny, but we knew how serious it was. It was unbelievable how bad it was at times.”

“As the pills took over,” says Western, “it became a nightmare. The way the show worked, I would do the first 20 minutes singing then I would MC the show. Many times, he shouldn’t have been on the stage at all. I would go on and say: ‘Folks, this gentleman really belongs in a hospital, but he wanted to come out and give you what he could because you’ve paid your hard-earned money to see him, so he’s gonna do his best.’

“Sometimes he was so hoarse from those pills that he was just croaking: he didn’t even sound like Johnny Cash. But the people loved him so much that they gave him standing ovations anyway.

“He took me to Carnegie Hall and the Hollywood Bowl and the greatest places in the world, and he took me to my wit’s end. When you love somebody that much and you can’t help him… it’s like an alcoholic: you can’t help an alcoholic until an alcoholic screams for help. Well, this was how it was with amphetamines and Johnny.”

_______________

Bill Walker, who later became musical director of Cash’s television show, experienced Cash’s unreliability when he worked on Nashville Comes To Broadway, a TV special in which country stars collaborated with Broadway artists. For the closing medley, Walker compiled a 17-minute piece in which the Broadway singers sang country, and vice versa. It began with Cash doing “Walk The Line”, but as the intro played, Cash never got beyond the ominous hum which signals the start of his vocal. “He never could get started,” says Walker. “He was out of the show.”

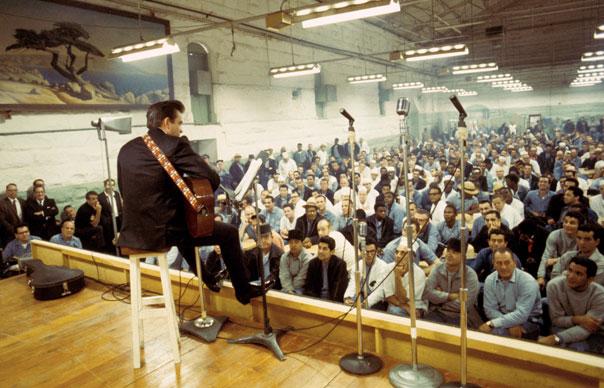

Cash’s addiction was threatening to entirely derail his recording career. “We’d reached a point where the drugs were pretty bad, and there was no growth happening in our career,” says Grant, “’cause we could hardly get him in the studio. That’s what brought on the Folsom album [At Folsom Prison]. We couldn’t get him in the studio, so we decided we’d record this album in Folsom. Columbia were reluctant to release it, but …Folsom was a monstrous hit. It remains to this day the biggest album we ever had.”

Cash had played prisons before. Western did San Quentin with him in 1960. “The first time Merle Haggard ever laid eyes on me, I was onstage with Johnny at San Quentin penitentiary on January 1, 1960. He was in a prison band and he talked about being a country singer when he got out. Next time I saw him, I was working a club in Bakersfield and he was working a club up the street, making $15 a night. He thought it was all the money in the world.

“What I learned that day at San Quentin was you don’t tiptoe around the facts. Those guys know they’re in prison, and you know they’re in prison. Well, a couple of opera stars came out – and one guy was singing ‘Ol’ Man River’. There’s a line in the song that says ‘get a little drunk and you land in jail’. He changed the word ‘jail’ to ‘trouble’. They booed him off the stage. If he’d said ‘jail’ they would have given him a standing ovation.

“Needless to say, Johnny’s first song was ‘Folsom Prison Blues’, and they tore the place apart. Later on, in 1969, he came back and did the San Quentin album, with ‘A Boy Named Sue’ and all that. He was a walking god with those prisoners. He was their main man. And he stayed that way, always.”

Millard Dedmon was a prisoner in Folsom on the day Cash performed in 1968, and can clearly remember the impact of the show. “I’m a musician myself, I’m a jazz enthusiast. But when Johnny Cash came in it didn’t matter what kind of music it was. It was a pleasure. I can remember just about everything about it.”

Cash’s last manager, Lou Robin, began by promoting his shows. One of his first tasks was to organise the 1969 San Quentin show which was filmed for a World In Action documentary.

“When that third steel door slams behind you, you know you can’t turn and run,” Robin recalls. “The mess hall held over a thousand prisoners – they were all sitting at the food tables watching the show. And the most prominent prisoners in the pecking order sat in front in tailored uniforms. I remember seeing one prisoner light a cigarette for one of these people. It just gave you an idea that it’s like any other organisation. There are people at the top and there are people that aren’t.

“I said to the head of security, ‘There are only about 10 or 12 guards in this place, is that enough?’ He said, ‘First of all, it’s enough. Secondly, if we had a hundred guards and these guys wanted to riot, what’s the difference?’”

_______________

The prison shows cemented Cash’s reputation as a rebel and repaired his status as a mainstream star. By the time he was given his own TV show in 1969, a semblance of stability had returned. “He was straight,” says Bill Walker. “He’d married June, he was off the pills.”

The Johnny Cash Show was a variety programme, and while Cash’s music was softened by Walker’s orchestral arrangements, the format was subversive. “John was very catholic in his tastes,” says Walker. “He could work with anybody. And he was a much better musician than a lot of people realise. His music was simple, but you could put Johnny into a situation where he was appearing with Ray Charles, and he’d be just fine. He worked with Billy Graham, with Tennessee Ernie Ford, it didn’t matter who it was, he could fit in.”

“He had a really radical TV show,” Kris Kristofferson recalls, “full of people like Dylan, James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, people who never came to Nashville – and he’d tell everybody in town that Blueberry [Mickey Newbury] and I were the best songwriters around. We’d all get together regularly at John’s house and there’d be a big circle with people passing a guitar around. I remember Graham Nash was there with Joni Mitchell and nobody knew who he was. We thought he was just Joni’s boyfriend. Then he picked up the guitar and sang ‘Marrakesh Express’. Knocked everybody out.

“To be endorsed by someone like Cash was really something, like being endorsed by Dylan. I watched Dylan record Blonde On Blonde in my first week at work at CBS. It was just incredible. I think because of his respect for Johnny Cash, he recorded in Nashville and made country legitimate to a whole new audience of people who’d always thought it was hillbilly music.”

Cash’s collaboration with Dylan on Nashville Skyline did much to cement Nashville’s reputation as a centre of musical excellence. Charlie McCoy, who played on Cash’s version of “It Ain’t Me Babe” in 1964, was session leader during the collaborations with Dylan which resulted in Dylan and Cash’s duet on “Girl From The North Country”. “Dylan and Johnny Cash really hit it off straight away. I think Cash really appreciated the fact that Dylan was trying to make some social statements. I remember it all happening very easily.”

_______________

Rosanne remembers the early 1970s as a great time for her father. “He was clean and he was strong. He was really healthy, happy.” She went on the road with the Cash show, officially as a laundry assistant, but gradually taking on more singing duties. “It was good. Then, in and out for the next few years he would have good years and difficult years.”

By the 1980s, however, Cash’s record sales were faltering. Columbia dropped him, and his new label, PolyGram, didn’t know what to do with him.

“Johnny didn’t get down when people weren’t buying his records in the ’80s,” says Glen Campbell. “He’d just go down in the woods for a while, and not meet a lot of people, and get himself together. He found the Lord, and that was a big, big thing for him. That helped him more than anything, I think. Reading the Bible will straighten you out a lot. That was one of the things that we talked about. And we’re both from Arkansas. We had more to rap about, because we’d done the same things growing up. We mostly talked about farm-work – riding the fence-rail, picking cotton, flopping the hogs, feeding the chickens, gathering the eggs. We were talking about it, and I said, ‘Well, John, are you glad you got out of that cotton patch?’ He said, ‘Who woulda thought it, man? Come right out of the cotton patch, and here you are playing to millions of people on a TV show.’ I said, ‘The Lord can do a lot for you.’”

But the 1980s were also a time of renewed drug abuse for Cash. Bass player Jimmy Tittle – who was married in 1982 to Cash’s daughter Kathy by Johnny, an ordained minister – recalls a period in which Cash was torn between the Bible and his addictions. “We were doing the Billy Graham crusades and we would go to Switzerland and you could just walk in to the drugstores and buy amphetamines. That and painkillers became the drug of choice for everybody.

“He would fight that all the time, and at the same time he studied his Bible constantly. He had a strong moral backbone, but that addiction is always nipping at your heels.”

“I worked all the CBS shows for him through the 1980s, and then he started to get really sick,” says Walker. “He was so fragile that if he got a toothache he’d have to go into hospital, and once they gave him a shot of a painkiller or something they had to bring him down again, because he was still hooked on those things. That was always a problem. He knew that if he went to the hospital he was going to be there two weeks.”

“In the early to mid-1980s, there were some shows that were pretty much unwatchable,” says Tittle. “From my point of view, standing behind him playing bass, he just was not there. He delivered a show in Las Vegas one time, and we would finish the song 30 seconds before he would finish his lyrics. It was like he didn’t know the difference. It got so bad June came out and told him to take a break. He came back and was somewhat together and finished the show. Anyway, I’m walking through the hotel after the show, and the crowd was going, ‘Oh man, did you see Cash? He was just so great.’ It was like people almost expected that of him.

“A lot of ridiculous things happened, like him and Marty Stuart backed a bus into a swimming pool in Florida going out to get a cup of coffee at four o’clock in the morning. He burnt a lot of cars up. A lot of accidents happened around him. But he was a sweet guy, man.

“Even that kind of tragedy had a humorous side to it. If it happened to anyone else they’d be going, ‘What a fool that kid is, his career’s over.’ But John could get into more stuff, and out of more stuff, than anybody I’ve ever seen.”

But Cash’s health declined dramatically over the course of the decade.

“John was really trying hard,” says Tittle, “going to the meetings. Even Waylon [Jennings] got sober. Then Larry Gatlin. All these guys got sober, and then I finally got sober. It was a real job staying sober, and none of us actually stayed sober for very long. When you went back to using, it was never the same: you always had the guilt. And it had worn his body out. That’s the time he went in and he had a lot of his stomach removed, from ulcers, from taking so many drugs – even Percodan and aspirin.

“He went from there straight to the Betty Ford Center. That’s when we did a family intervention. When he checked out the hospital in Nashville, they said, ‘Look, we just removed a third of your stomach, it had holes in it from your drug use, you’re gonna get sober or we’re all abandoning ship.’ And he went out to California and he got better. That was a tough period – he took about six, eight months off. But he took his health and his sobriety serious, from that time, for the first time.”

_______________

Even so, Cash’s recording career had stalled completely when Lou Robin took Rick Rubin to meet him after a show outside LA in 1992. “It was a very difficult time,” says Robin. “All the labels I talked to thought John’s popularity had run its course. So I took Rick to the dressing room. He sat down, and he and John stared at each other for two minutes, sizing each other up. And then they started to chat and found they had a common ground where Rick said, ‘You don’t need the orchestras. You just need to go and sing whatever songs you want to sing with your guitar.’ John never heard anyone say that to him.”

Rubin says that when he was a child, the Man in Black seemed “almost like a superhero”. He was surprised to find that Cash was shy, and though they didn’t talk much in that first meeting, they communicated.

“He was a private, quiet person. June balanced him because she was the exact opposite. Also it took the heat off him, because people were intimidated by him. His myth was intimidating, but as a human being he wasn’t at all.”

Under Rubin’s guidance, Cash’s creative reputation was rehabilitated, and though he was sick throughout the 1990s, the stripped-down style of the American Recordings gave them an intimacy and power that he hadn’t approached since the early Sun days. Cash’s story – his struggles and his pain – changed the meaning of contemporary songs such as Trent Reznor’s “Hurt” and Depeche Mode’s “Personal Jesus”.

“Thank God we had a guy like Rick at the helm,” says Tittle, “because Rick could read the situation and would hear a song that expressed how he felt. It was uncommercial, probably, but it didn’t matter. Because Johnny Cash was an iconic folk singer, to hell with being a country singer, you know? He wasn’t that ever, really. He just made music that mattered to him.

“Near the end when they thought he had Shy-Drager syndrome, he was shaking so bad and forgetting words, I’d see him and I’d say, ‘Oh man, he’s about to fall off, big time.’ I mean, he’s already fallen off, he’s about to fall down. I would try to stick close to him sometimes to just see where he was, but I could never tell. I always felt bad about that because he did have a condition that made him tremble – it was neuropathy, and I always thought it was pills. A lot of people did. There might have been pills in the mix, but it wasn’t to the extent that it used to be. They became more of a servant to him. He used to say, ‘Man, this arm is just bone on bone.’ And it was. He had worn out his body from the inside out, from the joints. And that really hurts. And I’m glad that he didn’t have to suffer and hurt, because it’s unbearable to be in pain every waking moment.

“He made beautiful art out of it. Even his voice in the last stuff he’s done, when it’s frazzled and sweet – it’s the most beautiful I’ve ever heard him. It’s so real. It’s a man that’s hurtin’; his heart’s broke. Especially when he goes to work after June dies, and you know his heart’s just crushed.”

“I remember one thing that I thought was kind of spiritual,” says Tom Petty. “The tape-machine broke in the middle of a particularly hot moment in the studio. And instead of freaking out, June came out in the room, where everyone was looking pretty low. And she said, ‘If we all sing a hymn, maybe God’ll fix the tape-machine.’ Not a procedure I had seen before! And John said, ‘Yeah, let’s sing a hymn.’ And June said, ‘Yeah, but we’ve gotta all hold hands,’ so we did. And I swear within minutes the machine worked. I always thought that was pretty interesting: that that would be their instinct if something was broken: ‘We’ll sing a hymn.’”

Nick Cave had a similar experience when recording a duet with Cash on Hank Williams’ “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry”. “I was sitting with the band and Rick, and then he appeared, and there were these steps that he had to walk down to the studio. Whatever the condition he had, if he went from light into dark he couldn’t see, he was blind for 10 minutes, so when he came into the studio, he looked real ill, and he had his arms out in front of him going, ‘Are you there, Nick? Are you there?’ And I’m like, ‘Fucking hell, how’s this guy going to be able to sing anything? Let alone get down the stairs.’ It was quite a shock.

“He said he’d had pneumonia three times that year, and he’d woken up and his voice had completely gone. And that he’d got down on his knees and said to God: ‘I never asked for nothing in my life, I never asked for nothing; but you give me back my voice! So I can go and sing with Nick Cave.’ Then he says: ‘And I woke up the next day and I’m singing like a bird!’ And June’s going, ‘Hallelujah! Hallelujah!’

“It was the real deal, and it was extraordinary. And when he started singing all his illness just seemed to fall away. He became energised. I often hear that, and often it’s a load of shit, but this is true. This real strength – this force of nature came out of him.”

“I experienced that myself,” says Rosanne, “when we did a duet of ‘September When It Comes’. He was so sick that morning. And I said, ‘Dad, you don’t have to do it.’ And he goes, ‘Well, I’ll give it a try.’ We went over to the studio and as he started singing he started to feel better. His energy came up. You could see it in his face: he changed. Then he wanted to do another take, then another. He exhausted himself, but it gave him back his life.”

When June Carter Cash died unexpectedly on May 15, 2003, there were fears that Cash would quickly follow her. Rubin spoke to him at the hospital soon after June’s death.

“He said he’d been in a tremendous amount of pain his whole life, and he’d never felt anything like this. He seemed inconsolable. And I’m listening to him speaking, but I didn’t feel like there was anything I could offer, because the hole he was in was so deep and so dark. He sounded terribly weak and terribly old – the worst I’d ever heard him sound – and I don’t know where it came from, but I felt like it was given to me to ask him about his faith. Which is something we’d never really discussed. I said to him, ‘Do you think you could find the faith to get through this?’ When I said that, something about that word ‘faith’ triggered a very strong reaction. His answer was, ‘My faith is unshakeable.’ And when he said that, he became a whole different person. He re-formed into strong Johnny. As soon as I heard that I knew everything was going to be OK.”

Cash was back in the studio days after June’s death, and told Rubin he wanted to have something to work on every day. The last studio recordings – on the unreleased American VI album – include the final song he wrote, “1st Corinthians”, in which Cash addresses death directly. “Oh death,” he sings. “Where is thy sting? Oh death, where is thy victory?”

On September 12, less than four months after June’s passing, Johnny Cash followed her to the grave.

“That was the end of it,” says Marshall Grant, “the end of a long, gracious career. He was one of a kind and believe me when I tell you, there will never be another Johnny Cash. Never.”

_______________

Was Cash a genius? “He wouldn’t think so,” says Lou Robin. “He was very modest about his accomplishments. He said he would record songs and if people didn’t like them they would throw them back at him by not buying the records. He was always very self-critical.”

“He was very wise to start with,” says Western. “Very intelligent for somebody that never got past the senior year in high school. I’ve heard from people that he had an IQ of around 160, which is borderline genius. He could write poetry when he was 12, 13 years old equal to that of great poets like Edna St Vincent Millay, who was one of his favourites. He was just a different kind of a guy. There was him and there was everybody else. We’re dealing with a genius mentality trapped in a country boy’s body.”

“He became a great songwriter,” says Grant. “Like ‘Ring Of Fire’. Anita Carter had the original version. When we decided we was gonna record it, I didn’t think too much of it, because I didn’t like Anita’s version too well. So he didn’t record it like Anita. He came up with his own plan. He had heard trumpets on that song. He was the only one in the studio who could hear them, so we called in two trumpets. And we changed it until we got what he wanted. On the second take, here was a song totally restructured. And he did it all. He told everybody what he wanted to hear.”

“Genius is a tricky word,” says Crowell. “But I think a song like ‘Five Feet High And Rising’ – that’s Faulkner. That’s genius. Or ‘I Walk The Line’, ‘I Still Miss Someone’, or ‘Big River’.”

“Oh yeah,” says Rosanne, “just read ‘Big River’ and tell me if that’s not one of the greatest pieces of Southern poetry ever written. ‘Big River’ is like Faulkner. Except it’s even more cinematic.”

“He had two gifts,” says Rubin. “The first one is his greatness as a man. The reason we love him as an artist is because of the man that he was, not because of his craft. It’s through his art that we get to see his beautiful soul, his incredible wise deep soul. He’s just a huge light.

“Then, when it comes to being a singer, his greatest strength is as a storyteller, and someone you believe. So when he speaks, he tells a story in a way that you know that it’s true. He imbues it with truth. He had an incredible ability to get across a point, through words, which is different than being a great singer.”

“Every day was fun with him,” says Tittle. “When you were around him, you felt better. You felt like anything was possible. Because he just exuded that. Even when he was kind of a frail old man in a wheelchair he was still the coolest guy in the world. And he had the most wonderful sense of humour. He always just lifted you up. He never once left me feeling anything but elevated. And I think anybody that was ever around him felt that way, man. You just didn’t want to leave.”

Crowell has a personal memory that illuminates the powerful charisma of the man. “I first met him at the Beverly Hills Hotel when I was dating Rosanne. We went to dinner in the bungalow, just me and her and John and June. You can imagine – I was 27 years old and they really treated me like royalty. John and June were world-class charming human beings. I was a couple of feet off the ground.

“The next time we met, Rosanne and I were living together, and John didn’t smile on that. He thought that was not right. We received a summons – airline tickets to their sugar plantation in Jamaica. I drank Bloody Marys to Miami and then switched to rum going down to Montego Bay, and when we got there I was up in my cups.

“There was a confrontation between John and Rosanne about sleeping arrangements, so with drunken bravura I cut into the conversation. I said, ‘You know I’d be a hypocrite if I changed my lifestyle.’ I was trying to be a puffed-up man and hold my own with one of the world-class icons. And he kind of looked at me, and he said: ‘Son, I don’t know you well enough to miss you if you were gone.’

“He dismissed me in a heartbeat, which instantly sobered me. And from that point on, he made a friend for life with me, because he just showed me what real strength is.”

Crowell also knows exactly where Cash should be placed in the landscape of American music, over which he towered, an unassailable legend.

“His face should be up there on Mount Rushmore,” he says. “Put John and Dylan and Chuck Berry, Merle Haggard and Hank Williams up there. It’s where he belongs.”

Additional interviews: Nick Hasted, Rob Hughes