Elvis Country is a return to roots. Released in 1971 at the height of country rock, the material – bluegrass, rockabilly, honky tonk, covers of songs by his heroes Eddy Arnold and Ernest Tubb – was deeply personal to Elvis. “Many of them were hits when he was just a kid,” acknowledges the archivist who helps compile Sony Legacy’s Elvis releases, Ernst Mikael Jorgensen. But astonishingly, it’s an album that seems to have been created almost by accident, in the middle of recording something else altogether.

Prior to the Elvis Country sessions, Presley had made a successful trip to the American Sound Studios in Memphis, which had yielded “Suspicious Minds” and the aforementioned From Elvis In Memphis, produced by Chip Moman. Moman encouraged Presley to work with material outside his normal range – including “In The Ghetto”. “They’d made a great LP in Memphis, and they should have cut there again,” says Elvis’ pianist David Briggs, speaking from his Nashville home. “But I don’t think they could get along with Chips Moman. It was politics and business.”

Elvis returned to Nashville, to RCA Studio B – where he’d recorded 18 sessions since 1958 – and his regular producer, Felton Jarvis, very different from the demanding Moman. “Felton wasn’t a musical guy,” says Putnam. “Felton was a pretty good judge of material that normal people would buy, and he was fun. Felton never got in the way.”

“Felton wanted to get it back up here where he could control it,” adds Briggs. The success of From Elvis In Memphis had been noted, though, as Putnam recalls: “Felton said, ‘I want you on the next batch of Elvis sessions, ’cos it’s got to be more like the American guys, and you guys are Muscle Shoals.’”

Elvis Presley walked into RCA Studio B at 8pm on June 4 to be greeted by some familiar faces – James Burton, who’d made his live debut with Elvis the previous year, David Briggs, harmonica player/organist Charlie McCoy and guitarist Chip Young. There were some new ones, too: the rhythm section of Putnam and drummer Jerry Carrigan – both Muscle Shoals alumni. In effect, this was a new band waiting for him.

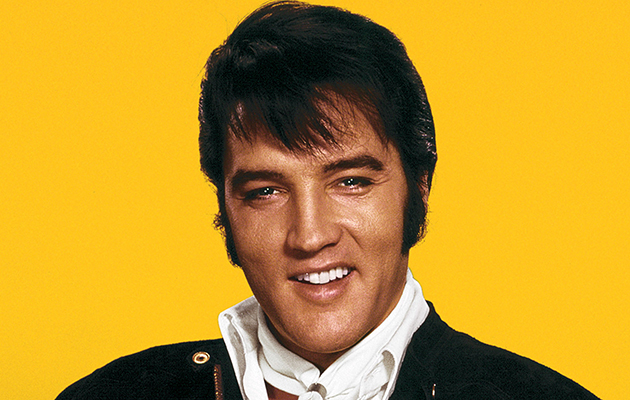

“I remember seeing him for the first time,” says Putnam. “He comes bursting into the studio, and he’s wearing a long black cape, and he’s carrying a walking stick with a lion’s head with ruby eyes. And he walked in like Prince Leopold, and took his cape off and he tossed it. He stood up and said, ‘I was wondering if any of you guys would like to help me make a few phonograph records?’ Then he burst out laughing, and he’s telling four or five stories, making us all laugh. He reminded me of the kids I knew in high school. He never wore that cape again. Maybe he was dressing up for the new boys. In 1970, he was in great physical condition, he was still working out with his karate every day. I looked at him when he came in, and thought, ‘He’s the most beautiful man I’ve ever seen.’”

Working with Elvis was a unique experience for the musicians. “Elvis was on a different planet,” Putnam explains. “In the control room would be all the Memphis Mafia and the publishing guys. And no matter how mediocre the first take was, at the end of it, they would leap into the air. They’re saying, ‘Gas, King! You’re the King! Touchdown!’ And we’re all going, ‘Boy, we could make this a lot better…’ But they all worked for him. Every man had a chore assigned. I remember one of them brought in a Halliburton briefcase. And inside was an arsenal of weapons. So he was obviously the security guy.”

Putnam also remembers some of Elvis’ more unusual studio practices. “Studio B was a very traditional, open room. Screens were available, but most nights Presley sang into this mic with a long cable, and he’d come out and stand in front of us, and he’d be dancing. It was very difficult for the engineer. He wasn’t interested in recording technique, whatsoever.”

“It was almost like he was doing a live show for you,” says Burton. “He’d be putting on a show for the musicians.”

According to Peter Guralnick’s Elvis biography Careless Love, a rack of clothes was available for costume changes. “He wasn’t changing clothes to impress you,” Briggs says. “He was sweating and felt dirty. He was working hard.”