The arrival of the Ornette Coleman Quartet in New York in the late autumn of 1959 represented one of the pivotal events of 20th century culture, comparable to the première of Igor Stravinsky’s Rite Of Spring in Paris in 1917 or Elvis Presley’s debut on the Ed Sullivan Show almost 40 years later. And, of course, with a similarly upsetting effect on the old folks. Jazz, barely half a century old, had grown used to an evolutionary process that took the music from Louis Armstrong to Miles Davis at a rapid but reasonably smooth clip. With very little warning, Coleman lit a set of booster rockets that fired the music into outer space. Suddenly musicians and observers who had thought of themselves as living on the leading edge of the music could be seen clinging desperately to the tail fins.

Coleman had entered the consciousness of the jazz world a year earlier with the first of two albums – Something Else!!!! and Tomorrow Is the Question – recorded for the Contemporary label in Los Angeles, where he had laboured in obscurity for several years. Among the listeners intrigued by their first exposure to his take on the conventions of modern jazz – seeming both sophisticated and naïve at once – were John Lewis, the cerebral pianist of the Modern Jazz Quartet, and the composer Gunther Schuller, a leading advocate of the Third Stream movement, an attempt to blend jazz and classical music. Lewis and Schuller believed Coleman was on to something important, and sponsored him and his trumpeter, Don Cherry, to attend the celebrated summer school at Lenox, Massachusetts. Lewis also alerted his friend Nesuhi Ertegun of Atlantic Records, whose artists included Charles Mingus and John Coltrane.

Before Coleman and Cherry left Los Angeles for Lenox in May 1959, Ertegun arrived in LA and took them, along with their regular bassist, Charlie Haden, and drummer, Billy Higgins, into a studio where, in one seven-hour late-night session, they recorded eight of Coleman’s compositions. In October, after their return from Lenox, they recorded another nine tunes for Atlantic. By then six pieces from the original session had been chosen to appear on the altoist’s first Atlantic album, which followed his former label’s lead in using a challenging title to attract interest and perhaps stir controversy: The Shape Of Jazz To Come.

The album was released that November to coincide with the New York appearance of Coleman, Cherry, Haden and Higgins at the Five Spot Café, a club on the Bowery which had acquired a reputation for presenting important developments in the music (Thelonious Monk and John Coltrane had played an important season there in the summer of 1957). Over the course of the next six weeks the entire New York jazz scene trooped along to check them out; many came back when the quartet returned from April to July, perhaps having readjusted their ears in the meantime. Some immediately recognised the authentic jazz qualities that lay at the heart of the music, principally a blues-drenched tonality and a commitment to rhythms that swung. Others were put off by the absence of normal harmonic structures. Coleman had abandoned chords and scales, moving on to a form of melody-based improvisation rooted in his own enigmatic theory of “harmolodics”, which even musicians who played with him for many years were unable to explain in conventional terms.

Some sceptics – particularly among older working musicians – saw one man playing a white plastic alto saxophone and another blowing into a miniature Pakistani pocket trumpet, noted the absence of traditional post-bebop structures, and concluded that this was music being made by clowns poking fun at predecessors who had studied and practised hard in order to succeed in a highly competitive and unforgiving field where your chops and your command of the materials determined your standing among your peers. Their scorn deepened when they heard Coleman’s claim to have “learnt how to play sharp or flat in tune.” To them a horn was either sharp or flat or in tune; only one of those three was a possibility.

For those with more open minds, however, the emotional content of Coleman’s music could not be ignored, particularly something as achingly beautiful as “Lonely Woman”, a ballad he had written a few years earlier while employed as an elevator operator in an LA department store, and now a jazz standard. At slower speeds, the very human “cry” at the core of his music reached back to much earlier forms of jazz, to a time before tunes were written down.

But the furore refused to die down, even though the succeeding Atlantic quartet albums contained pieces that would become standards, such as the backwoods-flavoured “Ramblin’” from The Change Of The Century, another in-your-face title for an album compiled from the second LA session, and the rollicking “Blues Connotation”, recorded during the group’s first New York session in June 1960 – with Ed Blackwell replacing Higgins on drums – from This Is Our Music. The latter album was released in 1960 with a cover photo by Lee Freidlander showing the four musicians posing together in business suits, white shirts and ties against a neutral background, enigmatically expressionless, looking like the prototype for every post-punk band there ever was.

The quartet’s music might have might converted the sceptics had not Ornette’s next project for Atlantic taken the form of Free Jazz, a 37-minute collective improvisation for a double quartet: himself, Cherry, Haden and Higgins plus the trumpeter Freddie Hubbard, the alto saxophonist Eric Dolphy, the bassist Scott LaFaro and Blackwell. Released in 1961 in a lavish gatefold sleeve with a cut-out window revealing Jackson Pollock’s painting “White Light”, it redoubled the challenge to Coleman’s listeners. The title was something of a misnomer – there were written themes and a steady rhythm – but the high seriousness of the endeavour was not in doubt.

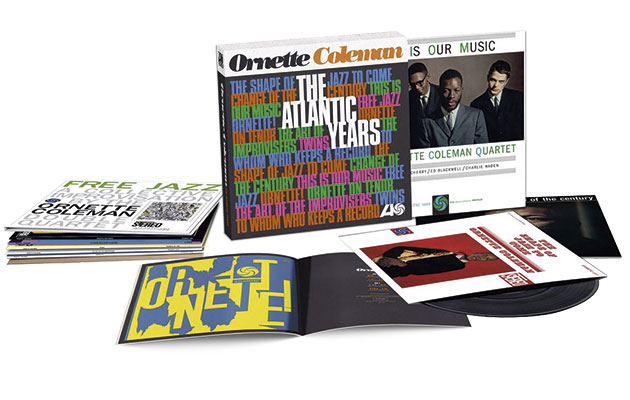

It was followed in 1962 by two further quartet albums: Ornette!, with LaFaro replacing Haden, and Ornette on Tenor, with Jimmy Garrison – from John Coltrane’s band – on bass. These six albums represented a body of work fit to stand alongside the likes of Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five and Hot Seven, Charlie Parker’s small-group recordings on Savoy and Dial, and the Coltrane quartet’s Impulse series in the jazz pantheon. For this vinyl reissue set they are joined by facsimiles of three further albums assembled in the early ’70s from the unreleased sides that had survived an Atlantic studio fire: The Art of the Improvisers, Twins and To Whom Who Keeps A Record.

A 10th disc is devoted to the six remaining tracks from the New York quartet sessions, previously included in a Rhino CD boxset (Beauty Is a Rare Thing) in 1993 but never available on vinyl LP. Five come from a four-hour session on July 19, 1960 which produced a remarkable 13 master tracks: there is little to choose between “Rise and Shine”, “The Tribes of New York”, “I Heard It Over The Radio”, “Revolving Doors” and “Mr and Mrs People” and the better known pieces recorded that day by Coleman, Cherry. Haden and Blackwell. The centrepiece of “Tribes” is a particularly remarkable drum solo, while Ornette’s solo on “I Heard It” contrasts broad smears with stabbing blues epigrams. The sixth track, “Proof Readers”, comes from the January 31, 1961 session that produced Ornette!, with the virtuoso LaFaro playing a role that, by contrast with Haden’s approach, is more conversational than supportive.

Scrupulous remastering of tapes originally recorded by the great engineers Bones Howe (in LA) and Tom Dowd and Phil Iehle (in NYC) and a thoughtful essay by the critic Ben Ratliff enhance the enjoyment of music that hums with historical significance while exploring a high proportion of the emotions to which the human race is heir. Essential, in other words.