“I’ve always felt that if you thought of it all as a book, then you have the Great American Novel… You take the whole thing, stack it and listen to it in order, there’s my Great American Novel. It tells you all about me, of growing up in the ’60s, ’70s and now the ’80s. That’s what it was like for one person, trying to do the best he could, with all the problems that go along with everybody.”

That’s Lou Reed, talking in 1984 in a quote reproduced among the memorabilia in the handsome book accompanying this big black box, compiling most of the albums he released in his first 16 years as a solo artist.

To stretch the analogy, the appearance of this set effectively breaks Lou’s lifelong novel into three volumes; In Search Of Lost Time in Aviator shades. Volume I is the Velvet Underground. Vol. III is the stubbornly unwieldy elder statesman era that commenced as the 1980s ended with two works of genius – 1989’s New York and 1990’s John Cale reunion, Songs For Drella – and concluded with 2011’s Metallica collaboration, Lulu, a record that revived a tradition stretching back to Reed’s earliest recordings: nobody got it except David Bowie.

Here, however, is the daunting and thrilling prospect of the monumental Vol. II: the 1970s and ’80s, when things got as strange and impossible to pin down as they ever did. Among the chapters included, after all, is Metal Machine Music, and elsewhere come paragraphs where he does nothing but chant the words “disco mystic” (1979’s mad and mysterious The Bells), or brag about how good he is at playing Robotron 2084 (1984’s underrated New Sensations, the Loaded of ’80s Lou).

It starts tentatively, with 1972’s self-titled solo debut on RCA, his return to music after – as Reed relates during an epic monologue on 1978’s phenomenal Live: Take No Prisoners – he’d quit The Velvet Underground to work as a typist. Why Lou Reed received quite such short shrift critically is slightly baffling. True, there’s something uncertain in the way Reed tries forcing discarded Velvets tunes into different singer-songwriter costumes. But the production is clean, the songs strong, and, although it can’t touch the (then-unheard) VU recording, “I Can’t Stand It” rocks hard.

Still, the explosion in confidence of Transformer remains staggering. A classic, of course, but the question of how much it is “a Lou Reed record”, and how much a Bowie/Ronson production remains. Certainly, it nagged Reed following the subsequent commercial failure of his painstaking magnum opus Berlin, when he made records he professed to hate, and they sold more than anything he’d ever done: the live metal panto Rock N Roll Animal, the trashy Sally Can’t Dance – sounding surprisingly good today.

The crisis peaked with Metal Machine Music and was obliterated in white noise. Lou at his poppest and softest (unless you count the killer “Kicks”), the following Coney Island Baby was his best rock’n’roll since the late Velvets, and its gorgeous title track led toward the increasingly personal, increasingly experimental, fusion-flirting albums he made when he left RCA for Arista: Rock And Roll Heart (on which “Ladies Pay” reveals he’d been listening to Patti Smith, and “Temporary Thing” is a buried classic); the great, speedy and awkward “Binaural” trilogy, Street Hassle, Take No Prisoners and The Bells; and Growing Up In Public.

Recorded after doctors warned him to clean up or die, the latter is, like Metal Machine Music, another seeming full stop, drawing the curtain on his wild 1970s. Over two years would pass before he re-emerged, returning to RCA sober, stripped down, and hooked up with ex-Voidoids guitarist Robert Quine for (the slightly overrated) Blue Mask and (undervalued) Legendary Hearts.

Quine left in acrimony, yet New Sensations was Reed’s best since Street Hassle, although few noticed. But the ’80s production helped underline Mistrial as, largely, a menopausal dip. Certainly, from here, no-one predicted the triumph of New York.

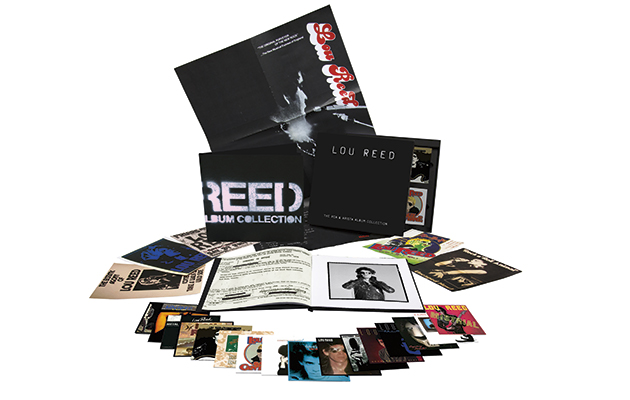

There is a lot to process. But in an era when deluxe boxsets are growing evermore expansive, it’s worth stating that – aside from the excellent book and some reproduction prints – what you get here is pretty much what it says on the lid: just the albums, as originally released.

There are no demos or outtakes, something collectors might find frustrating, given that earlier re-issues of individual albums like Transformer and Coney Island Baby came augmented by valuable bonus tracks. Perhaps, as Reed’s widow Laurie Anderson gets to grips with the rumoured “800 hours” of audio in his archive, rarities collections and live sets will come. (Please: put together a box of all the shows he recorded for Take No Prisoners, in the style of Coltrane’s Complete Village Vanguard.)

The big draw here is Reed’s own involvement. Unhappy with the treatment of his back catalogue in the digital age, he devoted his last summer to personally supervising the remastering of these albums, work carried out in New York City during 2013 in sessions recalled with great warmth by collaborator Hal Willner in the accompanying book: “Listening to each record and hearing Lou’s reactions, one could hallucinate back to the time they were made… The ghosts from the different eras were in the room.”

Two live albums are missing: Lou Reed Live (released in 1975, it’s Rock N Roll Animal II, featuring more songs from the same 1973 performance); and 1982’s Live In Italy. We can only assume that Lou didn’t have time to get around to those.

But this mighty thing is the writer doing one intense final proofreading, leaving us the corrected, authorised edition of his novel. And, possibly, having one last laugh, as audiophiles gather to scrutinise the new Metal Machine Music (I dunno… it sounds… warmer.) As far as the remastering, the Arista years benefit most ¬ these records sound better than they ever have on CD. This box’s real achievement, however, is shining light on so many semi-lost albums. Take the whole thing, stack it, listen to it in order. There are problems, sure. But there are worse ways to lose time.