Los Angeles in 1968 was a place of opportunity, a time when the freaks suddenly found themselves in control. Elektra had made a hit of The Doors, Warner Brothers had signed the Grateful Dead, and the Laurel Canyon scene was thriving. Suddenly a new breed of A&R man – hip, often hippyish, with solid underground credentials and the chemicals to back them up – were rubbing shoulders with the suits at labels across town. David Axelrod was no newcomer. He’d joined Capitol as a producer and A&R guy in 1963, making hits with R&B star Lou Rawls and the hard-bop saxophonist Cannonball Adderley. But as the ’60s bit, Axelrod – “Axe” to his friends – was increasingly developing his own vision: a sound patching baroque classical music to the engine of rhythm and blues, powered by a sense of spirituality that aspired to nothing less than the holy.

Axelrod had taken a maverick route into the industry. A white kid raised in the largely African-American LA district of Crenshaw, he grew up dirt-poor, and distinguished himself early on through his fists. A promising early career as a boxer was cut short owing to an eye injury that left him sheltering behind a pair of shades. He found his calling in the jazz clubs on New York’s 52nd Street, and on returning to LA, learned to read music under the tutelage of pianist Gerald Wiggins, finding his feet as a producer and arranger. Even as he refined a sumptuous orchestral sound fusing soul and jazz, Wagner and Stravinsky, something of Axelrod the brawler remained. “No matter how pretty his music is,” said Cannonball Adderley, “there’s always a layer of violence in it.”

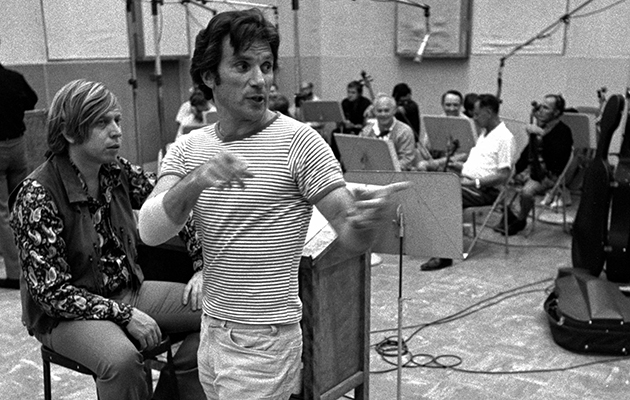

Nowhere in Axelrod’s discography is this duality captured plainer than on Song Of Innocence. Seven instrumental tracks packaged behind a blazing mandala, Axelrod’s debut as a solo artist – like its sister album, 1969’s Songs Of Experience – was inspired by the 18th-century poet William Blake, whose beatific, quietly revolutionary verse extolled the virtues of a humble life, close to nature and free from the “mind-forg’d manacles” of the society in which he lived. Recorded at Capitol Studios in LA, with a 33-strong band reading from Axelrod’s fastidious musical charts, Song Of Innocence combines bold strings and orchestral flourishes with a powerhouse rhythm section comprised of guitarist Al Casey, bassist Carol Kaye and drummer Earl Palmer – members of LA’s hotshot session players The Wrecking Crew.

Order the latest issue of Uncut online and have it sent to your home – with no delivery charge!

In a 1968 interview with Billboard, Axelrod identified his audience as “a new breed of record buyer… more sophisticated in his thinking”. The composer’s first attempt to reach out to this constituency had come with Mass In F Minor, a psychedelic religious opera sung in Latin, which Axelrod composed and arranged. The album was credited to the LA group The Electric Prunes, but the hapless garage rockers hadn’t the chops to complete it, so the band trickled off and Axelrod replaced them with Wrecking Crew personnel. Mass… was ambitious, flawed. But by Song Of Innocence, Axelrod had his sound bang on. Check “Holy Thursday” for a glimpse of Axe’s songwriting at its most refined and graceful. Kaye’s bass sits right in the pocket as divine strings sweep in and recede, the rest of the space coloured in with dancing vibraphone, bold chisel strokes of guitar, and climactic swells of horns.

Fifty years from its release, Song Of Innocence has undergone a refresh. The running time remains a lean 27 minutes, but a sensitive remastering job, overseen by the late composer’s producing partner HB Barnum, keyboardist/conductor Don Randi and his widow Terri leaves it sounding deeper and brighter than ever. “Urizen” sounds like a church mass overcome by Dionysian ecstasy, a punchy backbeat driving through rousing brass and fingers jamming over the keys of a church organ. “The Mental Traveler” combines spaghetti western guitar, the drone of a sitar and the dull ring of a gong to magical effect. Gentler moments like “A Dream” sit next to atonal string swells that set the teeth on edge. Melodic themes persist throughout, making Song Of Innocence feel greater and deeper than the sum of its parts.

Axelrod’s genius did not go unrecognised. George Harrison wanted to sign him to Apple. Now-Again CEO Eothen Alapatt, in this set’s extensive sleevenotes, revealed Axe told him Miles Davis jammed Song Of Innocence before embarking on his own fusion of jazz and rock, Bitches Brew. But the world turned, and by the late ’80s Axelrod and his wife were near penniless, living in a shack in the San Fernando valley, with ambitious works like Requiem: The Holocaust gathering dust on the shelf. Recognition came from a new generation of hip-hop crate-diggers, who started using his grooves as base material for their own productions. Everyone from Dr Dre to Lauryn Hill to Wu-Tang Clan made use of an Axe sample, and in 2004 two superfans – DJ Shadow and his co-conspirator in UNKLE, Mo’Wax’s James Lavelle – tempted the 73-year-old back to the stage. Axe appreciated this reappraisal in his own inimitable way. As he told one journalist: “I wasn’t into sampling ’til I started getting cheques.”

Following Axelrod’s death last year, many obituaries gestured to the composer’s influence on hip-hop. But it would be remiss to reduce his legacy to mere sample fodder. Song Of Innocence demands recognition too: in its swirling orchestration and broiling grooves, we get a glimpse of something unique – a daring, refined, deeply funky vision of the divine.