This article originally appeared in Uncut Take 163 from December 2010

This article originally appeared in Uncut Take 163 from December 2010

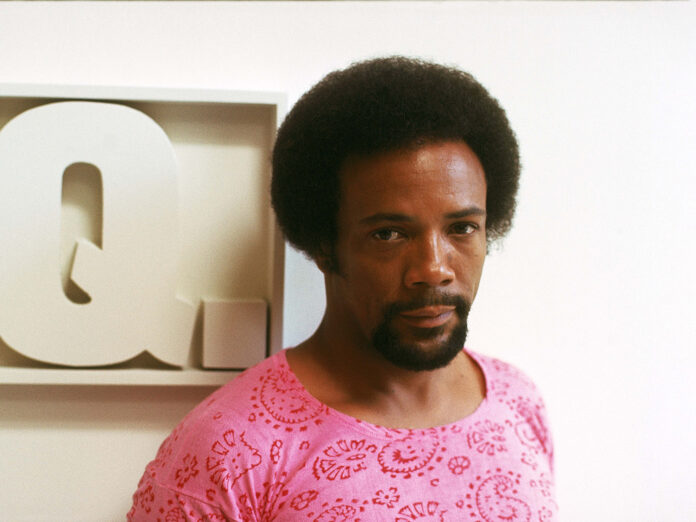

Quincy Jones keeps Uncut waiting for an hour before we’re finally ushered into his presence. Thankfully, this proves to be the only evidence of prima donna behaviour from the legendary producer and arranger – when we finally meet, he’s charming and affable, brandishing photos of his kids and relating tales of his extensive travels (China is a current obsession). As we talk through a handful of his many career highs, “Q” heads off on entertaining tangents: numerology, the banning of slave drums in 1692 America, the similarity between Chinese and African languages, the emotional pull of a major seventh chord and why Pro-Tools will never replicate his sound. In passing, he name-drops the Stones, Brando, Picasso and David Beckham. At 77, with a credit on over 100 albums, we have to ask what the secret is to his success. “The sequence is very important,” he says. “That’s the architecture of an album…”

QUINCY JONES

THE BIRTH OF A BAND

(MERCURY, 1959)

Jones’ third album was recorded half in New York, half in Paris – a reflection of how important the latter city had become to him in the late 1950s

JONES: I first came to Europe with the Lionel Hampton band when I was in my early 20s. In 1957 Eddy Barclay offered me the job of musical director at Barclay Records in Paris, which was great firstly because I also got to study under Nadia Boulanger, who had been mentor to Stravinsky, Aaron Copland and many other classical musicians. She was the lady. I learned so much from her – in New York they wouldn’t let you arrange strings if you were black – only horns or rhythm section.

Paris at that time was hot. Bardot was 24, Jeanne Moreau 23, I got to meet people like Pablo Picasso and James Baldwin. Lots of American jazz musicians went and lived in Paris because they loved the freedom and respect they got compared to back home. France nurtured jazz.

I went back to Paris in 1959 with an all-star band for the European tour of a Broadway show, Free And Easy. The band was terrific – guys like (trumpeters) Clark Terry and Harry Edison and (alto sax) Phil Woods, all the guys on Birth Of A Band!, but after the show bombed I lost a lot of money trying to hold the band together. That’s when I learned the difference between music and the music business.

RAY CHARLES

THE GENIUS OF RAY CHARLES

(ATLANTIC, 1959)

In previous years Charles had scored a string of R&B hits but after signing with Atlantic the scene was set for crossover success. Who better to help arrange than Ray’s old sidekick…

That was the first time I worked with Ray in the studio, though we had been friends since we were teenagers. He had wanted to get as far away from Florida as he could and that was Seattle, which in 1946 was on fire. It was a port for the Pacific Theatre in WW2. You could hear R&B, be-bop, any kind of music. The Chicago pimps moved there ‘cos that’s where the business was. We used to wear sailor suits because the sailors got the girls. That was an amazing time to come up.

After our paying gigs playing pop hits, Ray and I would go down to the Elks Club and play bebop all night for free. Ray sang like Nat Cole and Charles Brown and played alto sax like Charlie Parker. By 1959 he was a big star but controversial in the black community because he had taken gospel music and made it into pop records like “I Got A Woman”. Then he broadened out into big band jazz like Genius, with people from the Basie and Ellington bands playing. We did it again a few years later on Genius Plus Soul = Jazz, which has a great arrangement of “One Mint Julep”.

QUINCY JONES

BIG BAND BOSSA NOVA

(MERCURY, 1961)

A trip to Brazil in 1961 furnished Quincy with a new source of inspiration and another signature tune, “Soul Bossa Nova”, a swaggering big band blast still familiar two generations on through the Austin Powers soundtrack

We had previously made a State Department trip to the Middle East with Dizzy Gillespie, and it got back to Washington that we had done a good job. They said “We’re gonna send you to Latin America.” We went to Ecuador, Montevideo, Buenos Aires and finally to Brazil. Lalo Schiffrin (pianist and composer) had told me, ‘Wait until you get there!’ It was during the time that Antonio Carlos Jobim and Joaos and Astrid Gilberto and the rest of the bossa nova – ‘new wave’ – were happening. When you listen to it (hums Jobim’s “She’s A Carioca”) – all those flattened fifths in bossa, you can see how influenced it was by jazz. Everyone caught the bug – Stan Getz obviously, and Sinatra did an album with Jobim.

I still go every year to Carnival in Rio and then to see my friends up in Bahia for the carnival in Salvador de Bahia. Next year we’re planning a float in the Rio carnival parade for New Orleans musicians, have them meet up with Brazilians, and we’re gonna have William Friedkin [director of The Exorcist] shoot a film there for an IMAX movie, because a lot of Americ`ns don’t know about carnival, which is a spectacular and spiritual event. Imagine – all those girls dancing on a giant screen!

FRANK SINATRA

SINATRA AT THE SANDS

(REPRISE, 1966)

In 1964 Quincy had arranged a Sinatra hit, “Fly Me To The Moon”, which appeared on It Might As Well Be Swing, with backing from the Count Basie orchestra. When Sinatra decided to cut his first live album, Basie and Quincy were his go-to guys

I first met Frank when I was playing a gig for one of Princess Grace Kelly’s events in Monaco in the late ‘50s. He had me playing “Man With The Golden Arm” as he came on stage and worked the crowd, which included people like Cary Grant and David Niven, then he just took off into “Fly Me To The Moon”. Sensational. Then I worked with him and the Count Basie orchestra in 1964. Those were the days when singers were expected to deliver words like musicians played notes. Frank was actually the one who started calling me “Q”. When we were flying out to Vegas, he asked if we could play “Shadow Of Your Smile”. I said, Sure, as long as you know the lyrics. Then he wrote out the words over and over again and the next night he hit it perfectly – just check the record. And I worked with him again on ”LA Is My Lady”, one of his last records, in 1984.

Sinatra had certain catchphrases. He would say; “Q, live every day like it’s your last and one day you’ll be right.”

THE ITALIAN JOB

MUSIC FROM THE ORIGINAL MOTION PICTURE SOUNDTRACK

(PARAMOUNT, 1969)

Quincy had scored a dozen films by the time the call came to soundtrack The Italian Job – among them The Pawnbroker, In Cold Blood and In the Heat Of The Night. From The Italian Job an English national anthem would emerge …

I recall it well, as that was the time my son (Quincy Jones III) was born – he was born in London. We had a lot of fun doing the score – we were recording in the daytime at Olympic Studios where the Stones were cutting Sympathy For The Devil at night. Michael Caine would come by every day, then we’d go eat spaghetti con vongele in the King’s Road. Michael and I became great friends – I was with him and Shakira [Caine’s wife] just last month – and I discovered we were born the same year, day and hour – we’re celestial twins. Michael taught me cockney rhyming slang – “Watch the boat on the ice cream and check out the bristols on the richard.” No-one knows what you’re talking about.

I got an Ivor Novello award a couple of years ago and Elton John told me that only a Brit could write “Self Preservation Society”, which became the anthem of the movie, and I said wrong! Don Black did the words but I did the melody. I heard that they play it at every English soccer game – David Beckham told me that!

MICHAEL JACKSON

OFF THE WALL

(EPIC, 1979)

Prior to producing Off The Wall, Quincy was known as a jazz man and soundrack composer – the nearest he had come to making a crossover black pop record was working with guitarist George Benson on Give Me The Night. That was about to change

My connection with Michael came through love, like everything else y’know! I met him when he was twelve at Sammy Davis’s house. Then Michael played the part of the scarecrow in The Wiz (1978 Motown adaptation of Wizard Of Oz) where I was the musical director. On a musical the most important thing is the pre-recording because the movie is shot to that, at least the songs are, the score comes later.

Michael asked me for suggestions on who might produce his first solo album. I didn’t know how intuitive he was; he knew everyone’s lines, dance steps, he didn’t miss a thing. They were rehearsing one day and Michael’s thing was to read a famous quote – he pronounced Socrates as ‘so-crates’ and when I corrected him he looked like a deer in the headlights he said ‘Really?’. At that point I said I’d like to take a shot at his solo album and he said ‘Really?’ in the same way.

The record company said “No, Quincy’s too jazzy,” but that record saved half the A&R jobs there because it sold 12 million copies. I got Michael to sing “She’s Out Of My Life”, a song I was saving for Sinatra, and he cried during every take. The tears are there on the record, man.

MICHAEL JACKSON

THRILLER

(EPIC, 1982)

Where Off The Wall had been been recorded quickly, making Thriller sprawled over months, with obsessive attention to detail. Matters were complicated by the decision to make another album concurrently – E.T. , a ‘storybook’ of Spielberg’s feature film that Quincy scored and Michael narrated (it was soon wthdrawn as at Epic’s insistence). Deadlines loomed

In the summer of 1982 I had too many projects on the go. I was working on Thriller with Michael, working with the McCartneys, and working on E.T. To record Thriller I had three studios on the go – there would be Michael in one, Eddie Van Halen in another (Guitarist on “Thriller”), Bruce (Swedien, Q’s engineer and mixer) in another. We recorded a huge amount of material for the album. Then when we’d assembled nine tracks I took out the weakest cuts and put in “Beat It” and “Human Nature”, that really turned the album upside down cos we had “Billie Jean”, “Starting Something” and “Thriller”. It was incredibly strong. The sequence is very important – that’s the architecture of an album. When you have multi-producers you end up in trouble ‘cos they don’t have any sense of overal architecture and the dramatic sequencing.

Eventually we finished at nine in the morning after putting the overdubs on “Beat It”. I took Michael to my house and said Bruce is going to take the tape to get it mastered, so I got three hours sleep. When it came to the playback the album wasn’t working, so Michael starts to cry.

I’d been telling ‘em all along that if you want big grooves, you have to have 18 or 19 minutes a side, not 24 or 27 cos it won’t hold it, you get a tinny sound. I’d been asking Michael to cut down the introduction to ”Billie Jean” ‘cos it’s 11 minutes long and he’s saying “But it makes me want to dance,” and who are we to argue with him, us fat belly guys? Anyway we had to cut it down, take out a verse.

I’ve always tried to make records that have six exits and six entries so you can’t hear all of it at once; you have the bass line here, the backing singers there and so forth and you can’t hear it all, so you play it until the vinyl wears out and have to buy another copy.

Nobody knew Thriller would become the biggest album in the history of music, nobody, because that’s what God sends.

It never ceases to shock me that wherever in the world I go – and I travel constantly, man, I love it – that at twelve o’clock you are going to hear “Billie Jean” or “Wanna be Starting Something”. Else it will be “Ai No Corrida” from my album The Dude, or George Benson’s “Give Me the Night”. Absolutely everywhere!

MILES DAVID & QUINCY JONES

MILES & QUINCY IN MONTREAUX

(WARNER BROS, 1991)

Jazz’s dark prince finally acceded to Quincy’s request to revisit the tunes he’d recorded with producer Gil Evans in the 1950s on classic albums like Miles Ahead and Sketches of Spain. It proved to be Miles’ final album

Miles never wanted to do that concert. It took me 15 years to talk him into that. He was never one to look back, always wanted to keep moving forwards. His early stuff, though, has to be some of my all time favourite music. People always ask me how to get kids into jazz and I say “Give em Kind Of Blue’ and make them take it every day, like orange juice.” But I also liked Bitches Brew. People were telling us not to mix jazz with rock, that myopic mentality. That’s bullshit. Miles, Cannonball Adderley Herbie Hancock and myself used to talk about this, how you should try everything. We’d talk about rock bands. I used to say, “How come we’re drinking on a Saturday night and they’re the ones with the gigs?” One by one we expanded – Herbie wrote “Watermelon Man,” Cannonball did “Mercy Mercy Mercy”, I did “Walkin Into Space” in 1969 and Miles did Bitch’s Brew in 1970. See, the electric bass changed everything. That instrument was the one changed the genre – there would be no rock and roll, no Motown, no nothing without an electric rhythm section.

Montreux was the first time I ever saw Miles smile at the audience! He waved a towel at the audience and smiled. Once Miles had done the show he loved it. He said “We should take this shit all over the world.” I don’t know why he was so resistant, man, that was Miles. He was mad on technology, like Brando – they were complex guys.

QUINCY JONES

BACK ON THE BLOCK

(QWEST, 1989)

After three Jackson albums and We Are the World, had Quincy run out of road? Uh-uh. Back On The Block mixed old school talents like Ella Fitzgerald and Ray Charles with cutting edge rappers and mixed genres into a seamless whole. It won seven Grammys, including best album

We’d won Grammys on other albums like The Dude and Smackwater Jack, but nothing like Back On The Block. It had the widest range – be-bop, zulu music, soul…that’s my speciality, I love that conglomerate. It kind of ushered in hip-hop too, ‘cos we had Ice T, Daddy Kane, Melle Mel, Kool Moe Dee.

I’m all for the rappers, because the spoken word is the third genre after music and singing, right? It’s like praise songs in Africa. The lyrical skills are astounding but the lyrical content is often a problem and sampling is also a bad habit. I understand the fascination with gangsterism because I grew up in Chicago, the home of that stuff.

So a lot of hip-hop’s problems have a social source and that’s why I’m working hard now to build a consortium to get to the kids in school to know their roots. It’s crazy that kids don’t know about Duke Ellington and The Cotton Club. It’s starting to turn round – a lot of young guys come to me and say “I want you to teach me how to be a musician.” That’s the attitude we want.